First Caracol

Old Antonio used to say that the sky has to be held up so that it does not fall, because it is not firm over our heads, but every now and then it gets weak and faints and lets itself fall… and then calamities happen.

It happens that the first gods put all their effort into creating the world and when they finished it they were already tired and then they realized that there was no roof, so they put there whatever they could think of, in a hurry. That is why it is not firm and sometimes sags.

But the first gods, aware of the problem, left several of them in charge of holding it up when it shows signs of wanting to collapse; one of them keeps watch and when he sees that it might fall, he warns the others and together, they tighten the sky again and thus prevent it from collapsing.

This watchful supporter wears on his chest, hanging, a conch shell; with it he listens to the noises and silences of the world to see if everything is in order, and with it he calls the other supporters when he needs them.

The elders used to say that the spiral of the caracol (conch or the snail) represents the entrance to the heart, which is to say to knowledge. And they said that the snail also represents the going out from the heart to walk the world, which is like saying life. For all that, they said, the snail helps to listen to the farthest word, and with it the collective is called so that the word walks from one to another and the agreement is born.

That is the first Caracol, that of the originary peoples.

Second Caracol

It was July 1994. Seven months earlier, the Zapatistas had burst into history by taking up arms against the bad government. A war that lasted 12 days, as Civil Society entered into the conflict like a whirlwind, taking a stand for peace.

Not two months had passed when the parties met to talk in the Cathedral Dialogues, in the Chiapas city of San Cristóbal de las Casas. The government made promises and were astonished when the Zapatista representatives said they could not sign the agreement without first asking their people. “The war was decided in a consultation and peace will be decided the same way,” they said.

But in the long history of the native peoples, the promised promises never became reality and from the consultation came the rejection of the proposals and the II Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle, in which they called for the formation of the “National Democratic Convention” (CND), shortly before the presidential elections of that year, which Ernesto Zedillo would win. With the CND they wanted, among other things, to initiate a direct dialogue with the Civil Society that had established peace.

But they realized they did not have a place, a space to meet, to talk, and decided to build one; thus was born the Aguascalientes de Guadalupe Tepeyac, deep in the jungle. Its name recalled the place where the great Convention of Aguascalientes was held in 1914, the most representative assembly of the Mexican Revolution that brought together Villistas, Carrancistas and Zapatistas, in which the bases that would give rise to the Political Constitution of 1917 were established.

In Guadalupe Tepeyac they built an auditorium, a presidium, a library, a computer room, kitchens, lodging houses and parking. The fantastic thing was not that they built it in 28 days, nor that it had a capacity for 10,000 people; the fantastic thing was that they built a roundabout Caracol, without end or beginning, in which the auditorium and the presidium were in the center and the library at the beginning and end of the Caracol.

At one point of the construction there was a house that was poorly built, with a strange break in one of its ends; it seemed that the house was “crooked.” But it was not, it was simply the shape that the snail needed to draw itself.

In the opening speech of the National Democratic Convention on August 3, 1994, Subcomandante Marcos said: “Aguascalientes, Chiapas. Hope in staggered steps, hope in the palmitas that preside over the stairway, the better to storm the sky; hope in the sea snail that from the jungle through the air calls.”

On February 10, 1995, in the middle of an epistolary dialogue with the Zapatistas, the government presided by Ernesto Zedillo, immersed in a serious economic crisis, decided to betray its interlocutors and ordered the Federal Army to enter the jungle to detain the insurgent “ringleaders”; the forces that took Guadalupe Tepeyac, the first thing they did was to destroy the Aguascalientes. For some strange reason, the breaking point of the “crooked” house remained standing for several more months.

By the end of that same year, a new Aguascalientes grew in Oventik, in the Los Altos area, and soon after, new ones dotted the Zapatista geography: Morelia, La Garrucha, Roberto Barrios and La Realidad.

This is the second Caracol, that of the Zapatistas and their history.

Photo: Connor Radnovich

Third Caracol

In 2003, the Zapatistas decided to draw a new snail in their imaginary. Starting from the international, they spoke and thought about the national, the regional and the local, until they arrived at the “Votán, the guardian and heart of the people,” the Zapatista peoples. When they told us about the process, they explained that this was so, because first, from the outermost curve of the snail inwards, words such as “globalization,” “war of domination,” “resistance,” “economy,” “city,” “countryside,” “political situation”… are thought of. At the end of that path from outside to inside, in the center of the snail, only a few acronyms remained: “EZLN.”

Then, they went the other way around, from the inside to the outside, and only one phrase remained: “a world where many worlds fit.”

When this happened, it had been two years since the political class had thrown its final betrayal in their faces, approving a wrongly named “Indigenous Law” that did not comply with what was signed in the San Andres Accords on indigenous rights and culture; for a year and a half, the Zapatistas adopted silence and continued working on the process of building their autonomy.

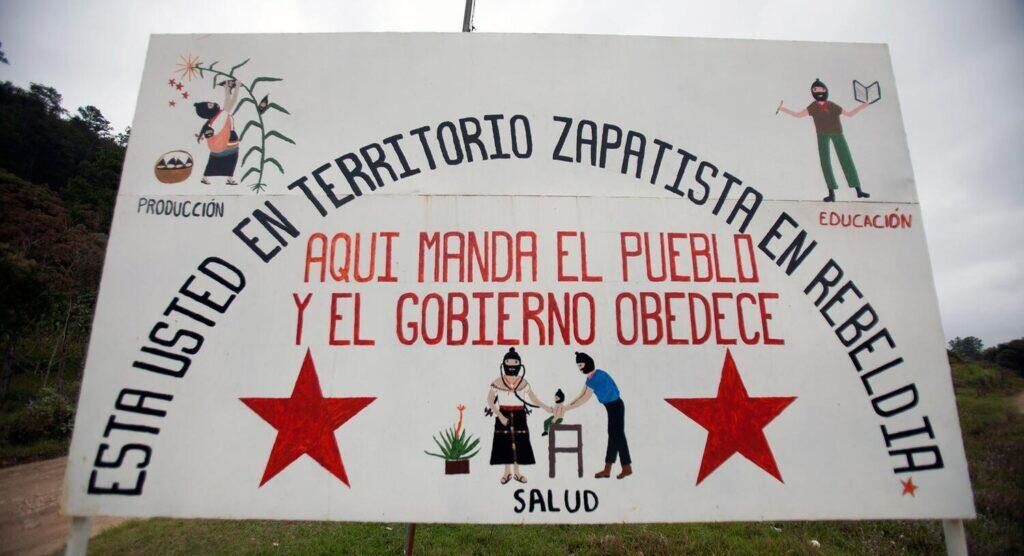

In July 2003, with the idea that the Caracol is the ideal vehicle for the word to enter and leave and also for it to reach further, the old Aguascalientes died and gave way to the new Caracoles, the spaces that would house, for 20 years, the Zapatista Good Government Councils, presided over by a sign that says: “You are in Zapatista Rebel Territory: here the people rule and the government obeys.”

In 2019, the initial five Caracoles became 12. Zapatismo grew, the zones grew, and the Caracoles expanded, thanks to the political organizational work of women, men, children and elderly Zapatista support bases.

In November 2023 it was made public that the Zapatista autonomy was reorganizing. Turning the pyramid upside down, turning the existing structures upside down, the Good Government Councils and the Autonomous Municipalities would disappear so that decisions would continue to be made at the grassroots, in the communities.

But we will talk about that some other time….

For now, this is the third Caracol, that of Zapatista autonomy, which with its spiral of beginning and end, continues to be the place of encounter, the place of the word and the place of listening.

This text is based on the following Communiqués of the EZLN that can be found on the Enlace Zapatista web page:

- National Democratic Convention. Speech by Subcomandante Marcos. 03/08/1994.

- “The Snail of the End and the Beginning”. 23/10/1996

- Chiapas: the thirteenth stele. First part: a snail. 21/07/2003

- Chiapas: the thirteenth stele. Second part: a death. 21/07/2003

- Chiapas: the thirteenth stele. Third part: a name (The story of the holder of the sky). 21/07/2003

- And we broke the siege. 17/08/2019

Original text by Lola Sepulveda of CEDOZ in El Salto published on August 4th, 2024.

Translation by Schools for Chiapas.