Attica was built to break men brutally, particularly Black men. Orisanmi Burton’s book, Tip of The Spear, draws a direct line from the “European trade in enslaved Africans,” to the bowels of D block Yard in Attica, during contemporary times where the cruelty is still ongoing and fresh. Humanhood required a response to this brand of oppression. “ATTICA! ATTICA!” The world came to shout.

Tip of The Spear speaks in the narrative voice of those men in Attica who refused to be vanquished. One of those voices is mine, although echoed from afar in time. The “Long Attica Revolt” sits inside a timeless context of human suffering and revolution. It “speaks to the very essence of this psychological war,” Burton wrote. Tip of The Spear captures this war of ideologies fought on the base level of society, where the bottom is filled with beaten Black flesh, gray ash, and rusty red coagulated blood. Over 40 years after the Attica uprising, Burton wrote my life on the pages of his work with their pain. This book review is my lineage, link and lock to the legacy of resistance! ATTICA! ATTICA!

Attica is a “site of war,” writes Burton. Attica was one of America’s last strongholds for patriarchal pride and white supremacy to operate with complete immunity to the law. After the Jim Crow era, Attica was the criminal justice system end game for Black men who resisted neo-slavery as a substitute for their civil liberties.

The societal structure for Jim Crow didn’t crumble. Instead, it evolved to criminalize being Black and poor. Then came mass incarceration. It began during the 1970s when former President Nixon declared a war on drugs and crime, thus Black people. Christian Parenti’s Lockdown America exposes former President Nixon as a racist when he, “invoked the specter of street crime, political chaos and narcotics abuse––much of which was thinly veiled code for “the race problem.” The political and social climate was akin to the social lynching Hilter launched on the Jewish people during the Holocaust through concentration camps.

Attica as a physical structure was designed to contain a human body in a cage. Each cell was meant to break the man inside those bodies it imprisoned. Finally, the overall desired effect was to breed what was left inside the body into a beast of burden. This process was all the more brutal when the bodies were Black. Burton calls this process of making a man into an object, “thing-a-fication.”

The prison’s organic culture of normalized cruelty against its influx of Black men as a result of Nixon’s war on crime and drug policies, produced prisoners like George L. Jackson. He was a revolutionary and theorist who was murdered in August 1971 by prison guards at San Quentin prison. Burton offers Jackson’s insight as to how Black people were to survive in prison under such conditions. “The Black commune is capable of nurturing a revolutionary culture and alternate modes of collective life.” Burton, George Jackson, and I don’t glorify the violence of the uprising on either side. Rather, we are romanticizing the humanity involved that came with struggling to survive the massacre.

No one heals in a steel cage. Instead you survive, and become further broken inside of it. Or, you harden from building yourself up against the bars. “It’s the other kind of killing, the kind that assails the body but truly targets the personality, spirit,” Burton reports. I agree because I was “one of those boys.” Burton wrote that people never came back the same.

In 1994, I was 16 years old, incarcerated, and sentenced to one to three years for drug possession. While detained on Rikers Island, I mentally and emotionally snapped after being locked in solitary confinement and repeatedly sexually assaulted by the Emergency Service Unit (ESU), while there.

“They herded us in like animals and forced us to lie on top of each other while guards made cruel and racist remarks like ‘Put that dick in him n**ger.’ Prisoners who refused were beaten mercilessly,” reported Black Panther Albert Woodfox. It’s the same way they did it to me. Except we were made to stand up naked and heel to toe.

From Rikers Island, I was shipped to an adult male prison, where I was supposed to be rehabilitated. No such thing happened. Instead, I was further animalized and released back into society, an 18-year-old wounded animal. A year later in 1997, I became a 19-year-old killer and was sentenced to 25 to life. Next stop for me was Attica.

Within the 30-foot-high gray walls of Attica Correctional Facility, brown and orange bricks stand sturdy, stacked and stained with human blood. Inside these draconian cell blocks, close and far-off screams shattered the mandate for silence while you suffer slow. Seeing the photos of Attica in Burton’s book transported me back to the first night I arrived there.

In 1998, the bright white lights of the newly renovated hospital were a fake out for what laid down the hall. The heat came rushing at me from the hallway and yelled! “WELCOME TO HELL ASSHOLE!” Upon stepping out the hospital corridor, any hope I had of leaving Attica alive evaded me.

The ideology of Attica has always been one of human torture. White guards habitually raped, murdered and brutalized Black flesh to emphasize terror and maintain control directly over the prison population. Burton elaborates that, “The White man’s ongoing effort to maintain racial and gender dominance helps explain why the political repression of Black men often takes explicitly sexualized forms.” Tip of The Spear collapses how we think about time, space, and the sequence of events that connect them. Instead it offers a narrative of a timeless suffering and struggle that roars in a single voice of resistance against an on going oppression. ATTICA! ATTICA!

One of those voices was mine. After numerous racist and sexual remarks about my anatomy during strip frisks, I rebelled.

“HEY FUCK FACE. ON THE NOISE OR ELSE I’M GOING TO TAKE ARTHUR’S DICK AND SHOVE IT DOWN YOUR THROAT,” yelled a guard to another prisoner being strip-frisked in the booth next to me.

Another time a different guard said to me during a strip frisk. “Arthur not for nothing, but if another Attica happens, just don’t fuck me up the ass with that n**ger stick huh.” Then he spit some tobacco off to the side and threw my underwear at me.

That’s where I drew the line. There would be no next time. I decided to wage my own personal war for dignity and respect. “They will never count me among the broken men,” George Jackson wrote. I would fall into the ranks of my revolutionary forefather and resist the strip frisk.

In November of 2002, I refused to be strip frisked after a visit with two women friends of mine. I said “No!” when I was ordered to remove my clothing in the small secluded booth. This activated the actors of the carceral state to beat me up, forcibly rip the clothing from my body, and probe my body cavities for contraband. No contraband was ever found. Yet, I laid there beneath the soles of their steel toe boots, a Black massive heap of hurting flesh. I recovered my pride as a man, because I took a stand.

“I became a man in Attica.” Despite its horrific history, “it’s where I grew up.” In 2015, that’s what I told journalist Alexander Nazaryan from Newsweek about my 13 years at Attica. It’s where I refused to be any longer what Burton refers to as “one of those boys that something happened too.” ATTICA! ATTICA!

In 2010, I left Attica hard as the rock I carried in my soul (see below), and wounded. Upon entering Coxsackie Correctional Facility, I found that the tension of Attica had tapered off somewhat. Things looked different, but inwardly felt the same. Despite the “Programming Pacification,” Burton explains, the atrocities didn’t stop. The oppression just changed appearance to the same effect. “The war was not over. . . it had only transformed in sophisticated ways,” Burton wrote.

Burton has convincingly proven that what happened at Attica in 1971 and the events leading up to its eruption wasn’t just a shameful episode in time. “State actors waged an imperialist war, a war of capture and conquest that had the production of slaves as its unspoken object,” Burton wrote about the premise of systematically putting Black men in prison. Attica also represents a deeply encoded strand of resistance within our DNA to oppression. I encourage everyone intent on taking a stand for what Burton calls “humanhood” to read this book.

Oppression and revolution go hand and hand. Burton’s work gives us a deeper and more profound look at, not just what happened at Attica, but also why Nelson Rockefeller, the Governor during the Attica uprising, described the state’s massacre of Black men in prison as a “really beautiful operation.” Eventually, if left unchecked the white patriarch imperialist will come to operate on you and your loved ones next. “Everybody is a n**ger,” if you’re not aligned with the white man, explained one survivor of Attica.

“Revolution must be a love inspired act.” That’s how George Jackson put it. That’s how it went down in the Attica uprising. Today I’m evolving the resistance, by the wisdom of Black lesbian feminist Audre Lorde. “You can’t use the master tools to tear down the master’s house.” Lorde also theorized “Black life as warfare,” writes Burton, who continues to make a brilliant use of Lorde’s “The Erotic” as proof that George Jackson’s theory of Black communal life laced with love is a reality.

Those men survived the Attica massacre because they practiced feminism, mutual aid, social care, and brotherly love. Albeit unconsciously, Burton’s interview with an Attica uprising survivor reports that “he witnessed someone spontaneously break into tears because he could not remember ever being so close to other people.” Decades later when I was in Attica I felt the same with my brothers in arms. Little did those brothers back then in the uprising, or I decades later would know, but we were being forged by feminism.

In 2020, the finer points of George Jackson’s and Aurde Lorde’s words would find me and force me to finesse my resistance with feminism. That same year Covid clapped the world. I led my prison community at Fishkill Correctional Facility as their Inmate Liaison Chairman through the pandemic while still resisting the carceral state without a single violent act. I employed love universally across the board to every human being on the compound. This is what Burton calls, “Humanhood.” This is how we all survived the COVID-19 crisis.

It’s also how I further resisted the state by beginning a movement with an art exhibit called “She Told Me To Save The Flower.” It’s my plea to use feminism as a way to heal in the carceral state as opposed to brutal cruelty. The global community heard my call and clicked up to crash the carceral state.

The Long Attica Revolt still resides with us today, although it has significantly evolved. New “technologies are also facilitating new forms of surveillance and control,” Burton asserts, and I agree. This book review has been censored by this same technology––JPay. Since you are reading this, we have successfully resisted the carceral state once again. Unfortunately, it’s not enough. The Tip of The Spear still needs sharpening by our strongest hearts and most brilliant minds. For every cry of oppression, there will always be someone resisting and shouting. . . ATTICA! ATTICA!

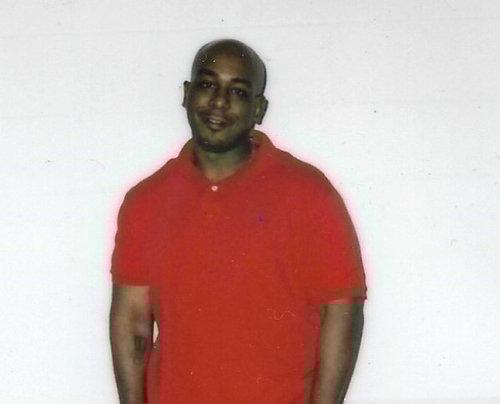

Corey Devon Arthur is an incarcerated writer and artist who is part of the Empowerment Avenue Collective, with his work published in venues including, The Marshall Project, Writing Class Radio, The Drift, and Apogee. He exhibited his art at 2 galleries in Brooklyn, New York in early 2023. You can check out more of his work at dinartexpression on Instagram, and on Medium.

From: Study and Struggle