Weeks ago, the Zapatista youth groups had meetings to see how they could promote the theme of “the common” among themselves and with the young partisans.

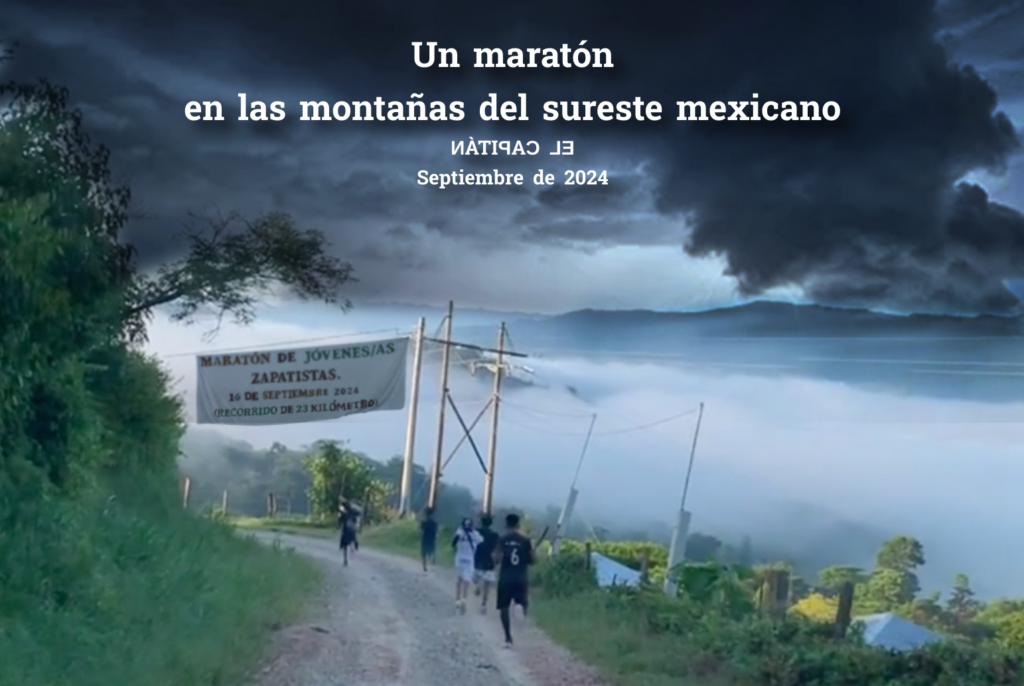

They came up with the idea of a marathon (of 23 kilometers) on dirt roads with steep slopes (i.e., “lomas” – as we call them here).

Their plan was that there would be no prizes for personal gain among the winners. Instead, the objective was that the prize would be a productive base to start first with the collectives in their villages. From there the next step is that projects of the commons can be created, where young partisans are involved.

The prizes were then breeding animals and farm animals. Although the breeding pairs would be for first place, all the participants would be awarded the money to buy chickens and start their projects for collective farms. The GAL (Local Autonomous Government) of each village will take care that the commitment is fulfilled and will ask for reports.

This is what they explained to me that they would do and (they are Zapatistas), so they did it.

They chose the date of September 16 to thus celebrate the beginning of the war of independence and the place that in that process -and throughout the history of this geography called “Mexico”-, the original peoples had and still have.

According to what the Tercios Compas of the zone tell me (Note: the “Tercios Compas” are groups of young Zapatistas who do media work: from taking videos, editing them, making recordings, radio programs and sound recordings; to “covering” what happens in their towns, regions and zones), the marathon began at 3 a.m. national time (4 a.m. southeastern Zapatista time), and, from two starting points, would converge in the Puy (or “caracol”) of Dolores Hidalgo. There would be categories of “jóvenas” (young women) and “jóvenes” (young men), that is, women and men.

Although there was no age limit, some 200 Zapatista young men and women registered. Their average age was under 20 years old, but the majority are young men and women between 12 and 16 years old.

The youth groups that did not participate in the marathon were organized in such a way that some of them covered the start with cheering slogans; others covered the finish with cheers and targets; others went in trucks cheering them on the road in case someone fainted, and with music and words of common sense as they passed through the communities; and others were in charge of the talks about independence, the awarding of prizes to those who participated, and the dance at the end of the marathon.

Those who arrived first arrived about 3 hours after the start. But most were still a third to a half of the way there. Those who were coordinators consulted among themselves as to whether the missing people had already been picked up and transported in the trucks. It was agreed that they would ask those who were en route.

According to what I am told, the compañeras who were offered the chance to get on the truck refused, replying, more or less, something like “Of course not. We are going to get where we have to go, it may take a while, but we are going to get there, even if we have to crawl.” Upon hearing this answer, the men also had to refuse to be “rescued.”

And, in effect, all of them arrived. In the evening they danced. And that is how the September 16 celebration went… in the mountains of the Mexican Southeast.

I can attest.

El Capitán.

México, septiembre del 2024.

P.S. OF MORAL IN THE FACE OF THE STORM – There were men and women who kept the pace and rhythm, and completed the challenge in the first places. The others explained: “they prepared ahead of time because they already knew what they were going to face.”

P.S. GENDER SELF-GOAL GOSSIP – The Zapatista special envoy on the scene told me: “The men arrived at the finish line and collapsed exhausted. With cramps and covered in dirt, lying on the esplanade of the caracol, they only listened to the slogans and the noise. One of the runners confessed: “uh compa, no way am I thinking about dancing, right now even my hat hurts.” On the other hand, the compañeras just drank water and asked what time the dance was going to be. While a group of young girls laughed and joked among themselves about how they had ended up, one of them declared: “We asked about the time of the dance to see if we could take a bath, or dance as we are, already the color of the earth.” They were all smiling happily. They had completed 23 kilometers of a thankless route, on which hills even motor vehicles struggle.

Mmh, I don’t think I’m going to leave this. It would be recognizing that the compañeras have more endurance than the compañeros, and gender solidarity prevents me from doing so. So delete this part.

P.S. TO GOSSIP. – And just like that, by the time the dance started, only the young women were kicking up dust to the rhythm of the cumbias. Only after a while, and in what is called “gender pride,” the men joined in. Grimacing and wincing, but without losing their composure, they said: “We’re fine, it’s just a new way of dancing that we just invented called ‘Cumbia de Esto te pasa por no prepararte para lo que viene’ (This is what happens to you for not preparing for what’s coming).

Echoes of a distant dance and a keyboard compete with out-of-tune crickets. A sparkle and the smell of tobacco barely outline a figure on the lintel of the champa. The night is already queen and mistress in the mountains of the Mexican southeast. Up at dawn, with a nagua of stars and a moon with a notched edge as a medal on its chest, it moves its hips to the rhythm of the “cumbia del Común”.

Again I attest.

The Captain.

Original Text and Translation published by Enlace Zapatista on September 17th, 2024.