Necibe Qeredaxi

From the moment humans become aware of their existence as a will, they have continuously asked themselves fundamental questions, always searching for the best and most satisfying answers that give meaning to their lives, both personally and socially. The question “Who am I?” has been the question of most truth-seekers, philosophers, prophets, and leaders of social movements. “Who am I?” might be one of the most important questions in the life of every ordinary person, regardless of color, ethnicity, gender, religion, sect, language, and culture. This question carries an even deeper meaning for individuals and social groups whose identity, existence, culture, and history are denied, or worse, face physical and cultural genocide. It becomes a catalyst for different kinds of action compared to others.

This begins at an individual level, becoming a driving force for self-questioning and later transforms into consciousness. In this process, these people consciously search for each other to reach the level of a self-defensive group. In doing so, they work together to build something new and prefigure a different form of life, one that stages their existence against the forces that deny them, both as individuals and as groups. The success of this process of question and answer depends on individuals being immersed in their historical memory. A memory that, with every change, both preserves the roots of its identity and renews itself, being reborn daily.

This process needs other motivations as well: consciousness from the depths of historical and social memory, courage and persistence despite obstacles, determination for all steps including self-sacrifice, the power to struggle against all ugliness, and commitment to promises with those who searched for each other in the initial steps and found each other within the circle of this search. Without extending this introduction further, I will discuss steps that indicate such a birth. Not just a physical birth, but the process of birthing a new identity, beyond that lack of identity and beyond the identity that the ideology and knowledge of those in power have imposed throughout history, especially on women. At stake, are processes of rebirth and self-construction.

One of those people who gave profound meaning to this process from the stage of self-awareness until the age of 56 was Sakine Cansiz, known as “Sara.” She was born on February 12, 1958, in a cold winter in the village of Takhti Khalil in Dersim, Northern Kurdistan, 20 years after the greatest genocide of the 20th century (the Dersim Genocide of 1938). Her parents, grandmother, and many relatives were survivors of the Dersim Genocide. In those extermination campaigns by the Turkish state, being Kurdish and Alevi wasn’t the only crime – being a woman in Kurdish society, trapped between state occupation and tribal relations, was to be in a paradoxical situation. On one hand, they were a weak link of subjugation and multiple layers of occupation, and on the other hand, they possessed an energy always ready for rebellion.

Sakine was the eldest daughter of the family, carrying many household responsibilities. Her mother was a rebellious woman, while her father was a calm and patient man. In general, due to the influence of Alevi culture, women were respected in their family. Sakine was mostly influenced by her grandmother. In the first volume of her book My Whole Life Was A Struggle, Sakine Cansiz describes her grandmother this way:

“My grandmother’s characteristics always caught my attention, I admired her and observed all her behaviors… She never extinguished the fire. At night she would cover it with ashes and start uncovering it again at dawn. For her, it was a sin to go to another house to bring or give fire. If someone asked for fire, she would get angry with them and advise them to keep their own fire under ashes from the night before… For Eze (grandmother), life was about maintaining the fire, praying during lunar and solar eclipses, and being connected to the earth.”[1]

The saying that nature is humanity’s first teacher perfectly fits Sakine’s grandmother. How could one not learn the spirit of patriotism and connection to land and society from her! When she would pray facing the sun daily, saying:

“O Angel of Dawn, who created earth and heaven

Write good fortune for us, poor and innocent humans

O Mother Fatima, O Hazrat Ali, Hassan and Hussein, take up your sword

Be a shield for our youth, protect them and save them… Show your bravery

Free Kurdistan and Dersim. O Khizr, Great Khizr”[2]

It’s likely this is the same “Khizr Zine” that we are familiar with from our grandmothers’ stories. Sakine attended primary school in Khozat and completed middle school there as well. Her sister recalls a notable moment from that period regarding their father, saying:

“At that time, our mother was in Germany. Our father would wake up early, brush Ferida and Nesibe’s hair, then Sakine would get us ready and send us to school before going himself.”

Initially, she only knew Dimli (Zazaki) because that was the dialect her family spoke at home. In school, Sakine learned Turkish through the education system, as Kurdish was banned from the establishment of the Turkish Republic until today. However, her mother always told her, “Never be ashamed of being Kurdish.”

In 1968, when the world was awakening to student uprisings and the ’68 revolution, and leftist groups were growing in Turkey and Kurdistan, Sakine’s first self-questioning began during her school years, starting with the language issue. Later, hearing stories of the Dersim genocide from elders, she became aware of the oppression faced by Kurdish society. Hearing about this oppression accumulated questions and the search for answers in Sakine, drop by drop, day by day. Although the elders whispered about these events out of fear, in that terrifying silence her curiosity for knowledge and her adventurous spirit began to emerge. Isn’t it said that “Freedom begins in childhood”[3]? From that stage onward, her determination showed that the elders’ fear created courage in her instead of silence, created curiosity and questioning instead of retreat. Rather than being a mere observer, she threw herself completely into the conflicts and questions, searching for answers.

Regarding Sakine’s first exposure to revolutionary life, Ali Haydar Kaytan (Comrade Fuad), who later became one of PKK’s founding members, says:

“It was 1974, in Dersim their house was in the Dag (Mountain) neighborhood. There was a large house next to theirs. We often stayed there, but occasionally visited that student house near Comrade Sara’s home. That’s how those comrades influenced Comrade Sara.”

Her brother Metin Cansiz describes those moments, saying:

“Sakine was mostly drawn to the leftists. She participated in their marches and demonstrations. She asked questions but never became a member of any ideological group. After she met the Kurdistan revolutionaries, she became very active.”

Her cousin Nurcan Yildirim, who was familiar with this period of Sakine’s life, says:

“It was 1974-1975, she talked about Kurdistan. In that city, I heard the word ‘Kurdistan’ for the first time from that woman. She would tell me about her student comrades, and there was a picture of Leyla Qasim drawn on her wall. She said ‘They drew it and gave it to me as a gift.’”

Her student comrades (who were the first group of Kurdistan revolutionaries) knew that her liberation-seeking tendencies as a woman drew their attention, and they saw her admiration for Leyla Qasim.

In the first volume of her memoirs, Sakine Cansiz writes:

“The inspiration they gave to political and revolutionary work put me on a path that changed my entire life. I knew several men who lived near our home; their lifestyle, their interactions, and their attitude toward values influenced me, and I saw the torch of Dersim’s freedom in them.”

After the 1971 military coup in Turkey, she connected with revolutionary youth and joined the revolutionary movement from Elazığ in Northern Kurdistan. About her interests, she says:

“I read many books, which brought joy and learning. There were ideological discussions, and those who defended these ideologies weren’t ordinary people. They had influential personalities and created enthusiasm in their surroundings. At first, everyone mocked them, calling them 4-5 rebellious Kurdish nationalists. Later, their name changed to Kurdistan Revolutionaries, and they were called Apocu[4].”

She actively participated and was present at the first revolutionary meeting in Dersim at the end of 1976.

Sakine always had conflicts with backward, imposing, and traditional attitudes. She was a woman who rebelled against customs and traditions. Sakine’s activism angered her mother. They were always fighting. About her mother’s personality, Sakine says:

“While she led me to develop a rebellious personality, she also taught me how to fight! I’m very indebted to her for that.”

Because she gave meaning to everything happening around her, instead of cutting off relationship ties, in her youth she tried to understand. This was the characteristic that attracted the attention of the first group of revolutionaries from the beginning, more than justifying the title that later became the name of her three-volume memoir: “My Whole Life Was A Struggle!”

In the winter of 1976-1977, the first expanded meeting of Kurdistan Revolutionaries was held in Dersim. For the first time, she heard the phrase “Kurdistan is colonized” from Abdullah Öcalan, the group’s leader, at this meeting which initially had 60 participants, in the house they called the “White Palace” in Dersim because it was painted white. For the first time, she became thoroughly familiar with national and class conflicts and embarked on a long journey that, as she says, “My Whole Life Was A Struggle!” She strived to ensure women had a role in the national liberation struggle and participated actively. For this, she was the first woman in the movement who organized women wherever she went.

During this period, Sakine Cansiz felt she could no longer continue living as an ordinary woman and searched for an alternative that would allow her to move more freely in revolutionary struggle. Sakine wanted to become a revolutionary and saw the solution in leaving home, searching for and finding an excuse, which was marriage. This path was an excuse and method for many revolutionaries at that time, as leaving home wasn’t easy for women. Sakine told her mother and family:

“I love Baki Polat, my cousin. He asked for me before and you didn’t agree. He’s a revolutionary and I’m going with him; he won’t prevent my revolutionary activities.”

Later, she married Baki and went to Izmir. However, Sakine had already left home and achieved part of her dream – she didn’t commit to married life because her goals were different. She worked at a chocolate factory for her livelihood while organizing women in general, particularly immigrant women workers from Eastern European countries in the factory.

After conflicts with her family, especially her mother, Sakine’s second conflict began with Baki after their marriage. On one hand, Baki was a member of “People’s Liberation” which, like its organization, didn’t see Kurdistan as colonized, and on the other hand, Baki Polat wanted Sakine to be a traditional wife solely committed to family life, which was impossible for Sakine. At the factory where she worked, she organized women and youth, leading to her and several others being fired. The workers began demonstrations and strikes. Sakine was arrested for carrying the banner whiuch read. “Kurdistan is colonized”. For these efforts, Sakine was taken to court, where she shouted “Down with the colonizer.” She wasn’t satisfied with just shouting slogans for “bread, work, and freedom” because she believed that in an occupied country and society where identity, history, and culture were denied, work and bread alone meant nothing. She saw true socialism in ending colonization and the joint struggle of peoples, and for this, she organized workers without discrimination.

Anyone somewhat familiar with Sakine’s life knows that she always took on difficult tasks. When she returned to Kurdistan, she began organizing women in Çewlig (Bingöl), one of the most conservative regions of Northern Kurdistan. In a place where people were afraid to even say they were Kurdish, she established several women’s groups of 3 to 5 people and gave women the courage to organize themselves. Despite family and societal barriers, women gathered around the slogans of the first revolutionary group and found themselves in it. Sakine had a great influence on them.

About this period, Sakine says:

“We said women must participate in the national liberation struggle, as this is how they can become free and take steps toward true freedom.”

Her first lessons for women were about the effects of the capitalist system on women, and she always said: “Women are viewed as commodities.” Women were initially uncomfortable with this term, but she patiently explained to them what she meant by the commodification of women. Sakine Cansiz’s struggle among women in Çewlig, Xarpêt (Elazığ), and other regions inspired the Kurdistan revolutionaries. She organized not only among women but in all sections of society. She created trust, belief, and hope in a people who had faced attempted genocide.

The fruits of her work in these later years had reached the level of beginning a new phase of struggle. The phase of moving toward establishing a revolutionary party that would answer the needs of freedom and independence for the phrase “Kurdistan is colonized.”

In the last week of November 1978, in the village of Fis in the Lice district of Amed (Diyarbakır), the movement’s first congress was held. Sakine Cansiz (Sara), along with Kesire Yildirim (Fatma), were the first women to participate in the founding congress of the PKK. She was very happy because they were preparing for a historic phase and filling a great void in Kurdistan.

While the manifesto and program were being drafted, Sakine was preparing for women’s struggle, and they even planned to call it the “Girls’ Group”[5], composed of all cadres and supporters. They researched women’s struggle and even prepared to write a pamphlet. Later, Sakine traveled throughout Kurdistan, following up on and analyzing women’s conditions.

From the movement’s First Manifesto, there was an analysis of women that stated:

“The destiny of women is like the destiny of the Kurdish people. Women must establish their own mass organization. If the goal is to build a democratic Kurdistan, then tribal and comprador pressures must be eliminated. Foreigners wanted to influence different social classes, but women are the segment of society they cannot influence. Women have been enslaved since the class society era.”

In 1979, after the congress, Sakine Cansız was tasked with organizing women in Elazığ (Kharput) and preparing for women’s education. Following organizational guidelines, women began studying Roman law and research on women worldwide. They started this struggle to build a foundation for women’s movement from 1979. Once, eighty women gathered in Dersim. Under normal circumstances, such a meeting would never have happened, especially since women couldn’t discuss their issues when men were present.

The state was aware of these steps and conducted operations against revolutionaries and other leftist and socialist groups. Regarding this time, Sakine said:

“It’s wonderful to fight and live with hatred against your enemy. I always told myself if our existence intimidates them, I should always be like a curse to them.”

On May 18, 1979, following a coup, Sakine and many of her comrades were arrested in Elazığ. In prison, she demonstrated strong resistance both against the prevalent tendency to surrender within the movement and against state authorities. The state used various torture methods including hanging, electrocution, solitary confinement in cold dark cells, stripping, force-feeding excrement, etc. Her resistance amazed prison officials. She stood very courageously against her torturers. The notorious Diyarbakır prison, known for torturers like Esat Oktay, was where he particularly enjoyed torturing Sakine and wished to hear her scream just once under torture, but she never did.

Sakine described the prison conditions by comparing them to Nazi camps, saying:

“Humanity in Nazi camps was a silent and shameless corpse, the body naked and exposed. Hope was killed in those meaningless eyes. Those corpses only moved when their turn for death came. If one asks if such a place exists on Earth, we don’t need to look far – there is Amed (Diyarbakır).”

When Esat Oktay confronted her saying “You must accept what is said, many have come and gone, do you know who I am?” Sakine replied, “Do you know who I am? I am a revolutionary, clearly you don’t know revolutionaries” – and when he attacked her, she spat in his face.

Let me translate and adapt this narrative about Kurdish political prisoner Sakine Cansız’s resistance and experiences in Turkish prisons:

The incident of spitting in Asad Oktay’s face became a legendary tale passed down both inside and outside the prison. Sakine’s stance led her to be recognized as a symbol of resistance throughout the women’s ward and the entire prison. The resistance of Sakine and her comrades during their hunger strike in Amed Prison became like a rebirth for Kurdish women and the Kurdish people in particular.

Her courage and bravery in prison impressed all the women inmates, both the political and non-political prisoners. One day, through a hole in their ward’s wall, they discovered that a prison guard was regularly spying on the women through it. When the women prisoners reported this to Sakine, she set up an ambush and stabbed the guard’s eye with a knitting needle. The guard screamed in pain, and Sakine was subsequently taken for torture because of this act of defiance.

Gültan Kışanak, the imprisoned HDP mayor of Amed who was in the same prison at that time, described Sakine:

“She maintained relationships with all prisoners. She would care for those who were tortured, massaging their bruised bodies to prevent blood clots after they were beaten with clubs and cables.”

Due to her acts of resistance against the prison administration and guards, Sakine Cansız was transferred to Amasya Prison. There, she was brought before the prison director named Şükrü. Their confrontation became an open defense of her political identity. When the director tried to establish his authority, saying “I am Şükrü, I have run this prison for so long that nothing happens here without my order,” Sakine responded defiantly:

“I am Sakine Cansız, a founder of the PKK. I am here now and I have my own principles! I recognize nothing else.”

While there, she made several escape attempts, but they were unsuccessful due to informants. Because of these efforts to break free from the cell that imprisoned her body she earned the name “Butterfly” from her fellow inmates.

In response to the September 12, 1982 coup, which aimed to break people’s will, only one window of hope remained: the resistance of revolutionary prisoners. Those who played a role in this resistance brought new life to a society on the brink of death. Kurdish revolutionaries understood two key points: first, that Kurdistan’s freedom as a national question depended partly on changing the mentality of the genocidal and denial-based state system, but even more importantly on the awakening of the Kurdish people themselves; and second, that the resistance and defense of a society’s identity and values in this movement wasn’t limited to men – women’s participation in this resistance opened the way for major social transformation.

Sakine Cansız’s resistance paved the way for both women’s and society’s freedom. From this emerged the slogan “Without women’s freedom, society cannot be free.” What had weakened Kurdish society wasn’t just the effects of colonization, but also the social illness and backwardness that colonization had internalized in Kurdish identity.

Sakine was the first woman in Turkey’s history to resist at such a level, becoming an exemplary figure of heroism. Sakine never accepted the conditions of an ordinary life and constantly struggled against such circumstances, never surrendering. She spent much of her youth imprisoned in various prisons (Elazığ, Malatya, Bursa, Amed, and Çanakkale).

In 1991, she was released. After her release, she went to the Mahsum Korkmaz Academy in Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley and participated in ideological education led by A. Öcalan. There, she participated in the first conference of political prisoners and later carried out organizational work in Palestine, Syria, and Rojava.

After this training period, Sakine requested to go to the mountains of Kurdistan. Öcalan, along with the academy comrades’ votes, agreed to her request to go to the Kurdistan mountains, believing that since she had played a role in the PKK’s founding from the beginning, he couldn’t make this decision for her. When most of the women comrades at the academy supported Sakine’s decision to go, Öcalan told her, “Sara, you won.” Sakine was overjoyed at this…

“I was very determined and stubborn – when I set my mind to something, I would definitely achieve it. Everything I wanted happened one by one. I saw the leadership, I saw half of Kurdistan, I saw and felt the love of people’s freedom. I told myself if I go to the mountains and my dream of becoming a guerrilla comes true, then everything will be as I wish.”

Sakine later went to the mountains of Kurdistan with great passion, participating in guerrilla activities and operations. She played an active role in the congresses and conferences of the Kurdistan Women’s Freedom Movement and the movement in general, having a decisive role in all conferences and congresses. She was also a powerful writer, which led Öcalan to suggest that she write her life story and memoirs.

Despite the harsh conditions in Kurdistan’s mountains, she maintained a very clean and disciplined life. Exercise was one of her passions and daily habits. She would wake up early in the morning and exercise in the mountain environment, even during snowfall, and collect spring herbs from the highlands. She loved writing her memoirs, always keeping her notebook in her bag, taking it out to write whenever she had the chance.

Öcalan, in describing Sakine’s character, could not hide his amazement and told her:

“You’re a very resilient girl. We put you through a lot of hardship, but this was certainly meaningless. What can we do? It’s our struggle and fighting that brought you to this level… You can be a well-rounded personality. Your courage and sacrifice, a hundred times more than mine, gave you strength.”

When the first autonomous women’s organization (Union of Patriotic Women of Kurdistan) was established within the movement in Hannover in 1987, Sakine was in prison. In the second congress held in 1989, Sakine played an important role by sending a guidance letter from prison that was read at the congress. The main topic of that congress was women’s autonomy (independent and special practices of organization) and how to develop it. From Kurdistan’s mountains, photos of 50 female guerrillas under the command of Comrade Azime were sent to the congress, creating great enthusiasm among women and presenting a new image for everyone.

The third congress of the Union of Patriotic Women of Kurdistan was held in Europe in August 1991, with approximately 1,500 delegates attending. The congress decided to establish autonomous education for women in the Kurdish language, taking a clear and powerful stance against ethnic cleansing. They also decided to publish “Jina Serbilind” (Proud Woman) magazine, which became the first women’s magazine.

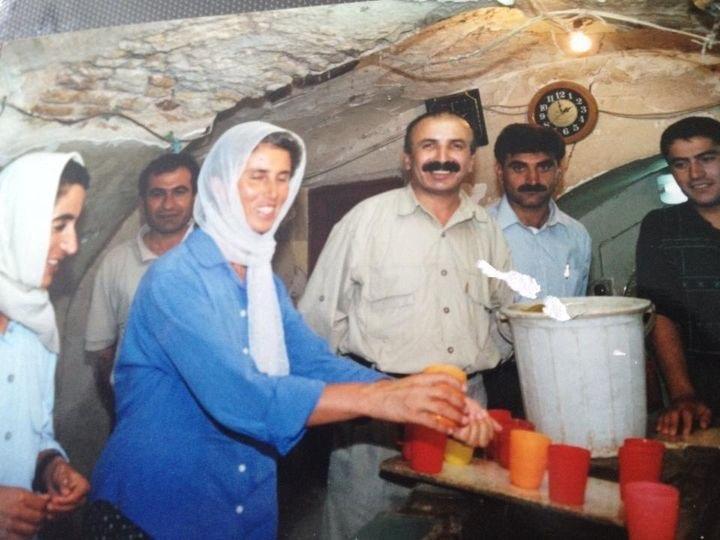

After returning to Kurdistan’s mountains, Sakine Cansız stayed in Botan in 1994. That year saw intense fighting, and she was part of the mobile unit, which was the most combative unit and faced the most battles. In 1995, it was decided to hold a women’s congress in Kurdistan’s mountains. Sakine played a key role in the preparatory committee for the first congress of the Kurdistan Women’s Freedom Union (YAJK). They prepared the movement’s bylaws, program, and reports in Metina, in Beshiri village, in a large historic cave symbolically called the “Women’s Temple.” The congress included representatives from all regions, with 350 female delegates participating. It was the first historical experience and step of the Kurdish women’s freedom movement in Kurdistan’s mountains.

This monumental step came after Kurdish women’s militarization. It was an army that would break through all inequalities, shatter the wall of fear, bring women out of their homes, and lead them to struggle. Beyond its military aspect, this army fundamentally uprooted the prevalent conservative mentality in Kurdistan and showed men the standards by which women wanted to live. In all these steps, Sakine was a collective pioneer. She deeply understood that Öcalan had addressed history’s deepest contradiction and that democratic change was impossible without this radical revolutionary approach.

Regarding this step, Sakine said:

“Women’s militarization wasn’t limited to just being an armed force. The creation of the freedom army meant ideological and political development, action, will, and the creation of power and morale. It also meant creating grounds for unity with the people. It meant addressing people’s main demands, organizing collectively according to people’s needs, creating an organization that would encompass all of these.”

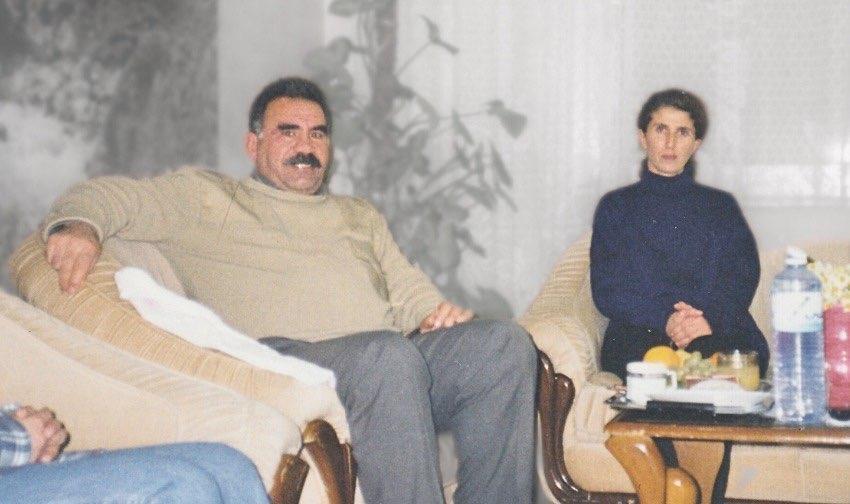

After gaining extensive practical experience in Kurdistan’s mountains, Sakine returned to the cadre training academy with a wealth of experience and theoretical foundation, where new perspectives and analyses were needed. At the exact time when Turkey and international forces were preparing a conspiracy network to expel Öcalan from Syria, during a Media TV panel with Abdullah Öcalan, Sakine, and several female comrades, the project of women’s liberation was announced. This is considered one of the most fundamental and important stages in the Kurdish women’s freedom movement’s struggle, occurring precisely when the movement’s ideology was being rendered increasingly meaningless by neoliberal propaganda waves globally.

This stage had been formulated in both theory and practice over many years to answer the question “how to live?” and required historically redefining the relationship between men and women in Kurdish society and beyond. Turkish journalist Maher Sayan, in an interview with Öcalan, described this relationship as “fire and gasoline,” referring to the transformation from a traditional master-slave relationship between a dominant man and a traditional woman to a free relationship. According to the women’s liberation ideology, this new relationship was based on principles of patriotism, struggle, organization, free will and thought, and ethics-aesthetics. This step would change not only Kurdish society’s destiny but the entire region’s, now having global reverberations. This was the historical, philosophical, and practical dialogue between Abdullah Öcalan and Sakine Cansız.

After the cadre academy training, Sakine (Comrade Sara) returned to the academy in 1998. Following new dialogue and sociological analysis with Öcalan, she moved her struggle to Europe, where she continued organizational work and opened a broader front in lobby work. She made significant steps both among Kurdish people’s friends and in diplomatic struggle. In 2018, during our first Jineolojî camp in Bilbao, Basque Country, we discovered that Sakine was the first Kurdish woman to visit Bilbao upon arriving in Europe in 1998, meeting with Basque women. Basque activist women and academics noted Sakine’s strong personality and broad intellectual horizon.

Whenever Sakine visited a home, she left a powerful memory and greatly influenced the development of patriotic spirit. She built comradely relationships not only with Kurdish homes but also with leftist, socialist, and internationalist figures, opening broad avenues for struggle, resistance, and collaboration. She introduced them to Kurdistan and the freedom movement, finding support for the freedom struggle.

Especially after the international conspiracy against Öcalan and his imprisonment in İmralı‘s solitary confinement, Sakine conducted lobby work country by country while explaining the difficult post-conspiracy period within the movement and society. Particularly regarding the paradigm shift to Democratic Modernity, which was both a strategic step and carried its own risks. Sakine worked day and night to maintain organizational unity and fulfill the Kurdish Women’s Freedom Movement’s strategic role in resolving historical issues, providing genuine leadership for women within the movement, whilst also protecting the movement and leading the process of socializing Kurdistan’s revolution. For this, alongside other leading cadres, she maintained a decisive position in all subsequent congresses and at the movement’s turning points.

Sakine was very confident that a crucial phase in Kurdistan’s freedom struggle was approaching. Speaking confidently on Roj TV on October 27, 2008, she said:

“There is an ongoing struggle that’s advancing. A struggle that has now become the Kurdish people’s own. It has opened the path to freedom for our people, paved the way for Kurdish people’s organization and unity, and has become the foundation for people’s self-determination.”

In a 2011 interview, published in Nawaya Jin magazine, and responding to a question about women’s responsibilities, Sakine said:

“We struggle so that we don’t become the women who can do nothing but cry, we struggle so we don’t become the women who wear black and lament their pain, that’s why we’re in the mountains… The pain and oppression that society and women have lived through in history and continue to experience today is about awareness, creating consciousness, thought and perspective, and means of struggle. We can only overcome this situation through broad organization.”

When discussions were held in Europe about establishing a Women’s Foundation and its name, it was suggested to name it after Sakine, just as many institutions were named after Rosa Luxemburg. At that time, Sakine said: “Why are they planning to kill me?” Evidently, she sensed that those who couldn’t eliminate her in prison or in Kurdistan’s mountains had pursued her to Europe. In the center known for ‘human rights’ and ‘democracy’, they succeeded in their conspiracy against her.

On January 9, 2013, at the Kurdistan Information Center on Paris’s busiest street, Sakine Cansız (Sara), Kurdistan National Congress member Fidan Doğan (Rojbin), and youth movement member Leyla Şaylemez (Ronahî) were assassinated by a member of the Turkish intelligence agency MIT. Later, the killer died in a French prison under mysterious circumstances, leading to the case’s closure.

The occupiers attempted to silence the voice of Kurdish women and the Kurdish people through the assassination of Sakine and other pioneering women. Their goal: to strike a deadly blow against the inspiring mind of this movement. However, Sakine, just as she had learned to succeed, became the voice and spirit of millions in the face of both death and her killers, as people poured into the streets to express their feelings about this massacre. She dreamed of being showered with flowers when received in Kurdistan as a guerrilla fighter. She carried the pain, suffering, and tragedy of her people in her bag, transforming it into hope, energy, awareness, and organization as she traveled from city to city, mountain to mountain, country to country. Yet she also understood that the path to peace is a long one.

Öcalan assessed this massacre and said:

“In reality, they wanted to use this massacre to prevent my peace efforts. That is, those within the state who don’t want the issue resolved through democratic means wanted to disrupt the process. Sakine’s life is an example. Women’s freedom is Sakine’s struggle. I will ask for accountability for Sakine, and I will reveal this…”

Source: Tawar Magazine

[1] – Sarah’s documentary https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oLiq0p6T1x4

[2] – Ibid.

[3] – A. Ocalan, Beyond the state and violance.

[4] The word apogee is an abbreviation for who belives in Abdullah Ocalan’s philosophy, the leader of the first group of Kurdistan revolutionaries.

[5] Dalal Amed, “Women’s History Lessons in the Kurdistan Freedom Movement”.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Sarah’s documentary https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oLiq0p6T1x4.

[8] Butterfly is a 1973 film about the life of a prisoner, directed by Franklin J. Schaffner. The screenplay was written by Dalton Trumbo and Lorenzo Semple Jr. and tells the story of a French prisoner named Henri Charier

[9] Abdullah Ocalan, Volume 1 of “How to Live”

[10] – (Dalal Amed), book “Lessons of Women’s History in the Kurdistan Freedom Movement”.

[11] – Ibid

source: Jineology