The EZLN celebrated together with its support bases a conference commemorating the 31st anniversary of the uprising in Chiapas, in which they reflected on the challenges that the movement is facing. Between April 13 and 19, they are preparing another event: the “(Rebel y revel): encounter of art, rebellion and resistance towards the day after.”

”When we say common, we say that it has to be of our life for centuries and for centuries, forever from people to people, unity,” explained the insurgent subcomandante Moisés last January 1 in San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Chiapas, where the meeting of “Resistances and rebellions” called by the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) took place between December 28 and January 1 of this year, as part of the celebration of the 31st anniversary of the indigenous rebellion of 1994. Now, between April 13 and 19 of this year, the organization is preparing to receive artists from around the world in a meeting called “(Rebel y revel) Arte: encuentro de arte, rebeldía y resistencia hacia el día después,” in three different venues in the rebel territory.

In December 2024 the Zapatista movement published that their new political strategy within their communities and autonomous regions would be the “komon” word used within the Mayan communities or “common” in the Spanish language. After a year, the Clandestine Revolutionary Indigenous Clandestine Committee General Command of the EZLN, led by Moisés, but also with Comandante David, explained in detail the “first steps” of this practice that is being developed in the Zapatista Mayan communities. Where does this idea and practice come from?

From semi-slavery to liberation

In the territory of Chiapas, by 1910, 92.8% of the peasant population were peons, which explains the inheritance of that regime and dominating power that allowed the concentration of land and labor force. Chiapas remained on the margins of the Mexican revolution, particularly in the agrarian distribution that took place since the 1920s. It did not even experience a “revolution from the outside”, as in Yucatan.

From the transformations of the post-revolutionary national State, until the 1940s, the process of making the legal framework for obtaining land more flexible and, therefore, the conversion of important extensions of land into ejidos stood out. This was the implementation of President Lázaro Cárdenas’ reform to the Agrarian Code of 1934, whose main objective was the recognition of the peones acasillados (farm laborers) who lived on the farms as subjects of agrarian rights, which meant that from then on they could also become land applicants. This also brought friction between the local oligarchy and peasants and indigenous people in resistance. The young militants of the EZLN, they were the ones who were born with the inheritance of the old peon farms and who also lived under the repression and the paramilitary groups at the service of landowners and corrupt politicians.

In the recent meeting for the 31st anniversary of the EZLN uprising, Moises made a strong criticism of the legal regime of peasant land that comes from years of experience: “Lazaro Cardenas when he gave the plots, in an ejido, one has 2,000 hectares, each (peasant) has 20 hectares. That’s where the problem comes from. Although they worked the land in common, there are no boundaries or fractions. They themselves allowed it, (they said) that it had to be divided.” This process of gradual transfer of collective property into individual ownership is in fact the historical process in which the legal framework of the nascent liberal Mexican State during the 20th century allowed the existence and even encouraged the “individual rights” of peasants. It is the incorporation of land into the regime of capitalist modernity.

Applicants for land, sometimes still peons or indentured servants, were repressed and in the best of cases, when some lands were legalized, the peasants were forced to subordinate their loyalty to the cacique, boss, political party or representative of the government in office. This was the difficult exit of the Tojolabal, Tseltal, Tsotsil and Chol Mayas from the period known as the “baldío”, in which the peasants worked “en balde,” that is to say, with miserable pay.

It was the decline of the plantation regime in whose experience the Zapatistas express it in the sense of “we left in a ball, in a mass” -and they continue- “They grabbed en masse and then they said we are going to work the milpa in common, our houses in common. We realized that it is better, this way nobody says that this land is mine, this is mine, that is where the anger comes from, the fight of one people against another, (but) this common sense has not been understood because of individualism.”

When the indigenous populations of Chiapas became politicized through the influence of liberation theology, a broad conscientization was awakened that in practice allowed the deployment of this liberation struggle and allowed them to leave the regime of semi-slavery exploitation of the old farms, seeking the exodus to the Lacandon Jungle in a “ball” and as a collective. They brought their common customs and the sense of that “promised land” without the old humiliation of bosses and foremen and that gave strength to their rebellion almost twenty years later.

In 1974, the fourth centennial of the death of Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas, one of the defenders of the indigenous people, was commemorated and celebrated. An important work of awareness of the historical context and the social participation of 1,400 delegates from more than 500 communities had already been undertaken. The meeting allowed an important grassroots politicization.

In 1984, the ruling classes left behind the welfare state and neoliberalism was imposed in Mexico, which began the privatization of national enterprises. By 1991, the neoliberal reform of President Carlos Salinas de Gortari irreversibly modified Article 27 of the Constitution, allowing the sale/purchase of peasant ejido land. The EZLN took up arms in 1994 and despite the 1996 San Andres Accords on culture and indigenous rights, communities were left at the mercy of the penetration and expansion of “legalized” capital, as well as paramilitaries, organized crime, and drug cartels.

What has changed?

Despite the arrival of the “institutional left”, the so-called Fourth Transformation to power in 2018, the San Andres Pact was not fulfilled. It even expanded the free entry of savage capitalism in Chiapas. The current Zapatista critique even maintains that a peasant social class capable of accumulating wealth and goods has been created: “There are already medium-sized landowners, whoever lent money to a migrant, kept the land. Now any narco-businessman can buy what used to be ejido, what used to be common,” explained Subcomandante Moises in that January meeting. That is to say, there is a free entry for those who have ties to crime to even buy peasant land that was previously protected by the state’s political constitution.

But the “progressive” government of former President López Obrador incorporated another program that represented the greatest penetration of capitalist modernity in Chiapas with the official “Sembrando Vida” (Sowing Life), which intensified not only the buying and selling of land, but also dispossession. “They tore apart the ejido lands, before (a peasant) had the right to 20 hectares of land. But with this program it is divided into 8 pieces. Each farmer gets 2 and a half hectares and with the right to sell it,” said Comandante David.

“There are people who sold their plot of 20 hectares. And the one who left as a migrant and came back, he himself is working on that which was his land.”

This program, promoted by the governments of the Morena party, has led to peasants who used to cultivate the land now receiving cash to plant timber or fruit trees. The peasants take the money, get themselves into debt and then migrate. When they return because they have been deported or because of the death of a family member, they go back to their place of origin to work as employees sometimes on what was their own land, that is, this process is revealed as the mirror of the times of the abandoned land. “Many are already on the street with the “sowing death” program. There are people who sold their 20-hectare plot. And those who left as migrants and returned, they themselves are working what used to be their land,” said the military commander in front of almost a thousand Zapatista support bases in the Indigenous Center for Integral Training-University of the Earth.

When the indigenous peasants perceive the ease with which they can divide the inherited or recovered land and take advantage of it momentarily to migrate, then the dispossession is implemented. Sold at a low price, some small landowner will have control and ownership of the land. Now even the former owner of the land loses his communal rights because of the cultural illusion of modernity: “Those who have migrated, it is not because they are poor, it is because of the capitalist system of fashions, so everyone wants to have their watch, their new phone, their latest models. So they leave,” said Moisés.

In Chiapas, the Fourth Transformation does not imply the benefit for the peasant population, but rather a change in land use and rent. It is a deception that provokes the increase of individual landowners and the accumulation of capital. In its neoliberal form, this relationship is creating a social class of small and medium landowners who used to be peasants and are now landowners.

Faced with this situation, the “common” means returning to that komon a’teltik, which in the Mayan Tojolabal language means, “our work in common.” This collective project unfolds as a policy of liberation and a commitment to life and peace. Generous as it is paradigmatic, the EZLN is lending land to those who lost their property rights because they sold their land and/or migrated, even to non-Zapatistas. With this strategy, the Zapatistas are preparing for that day after the foreseeable capitalist collapse: the hopeful challenge is undoubtedly the sense of community, the “commons.”

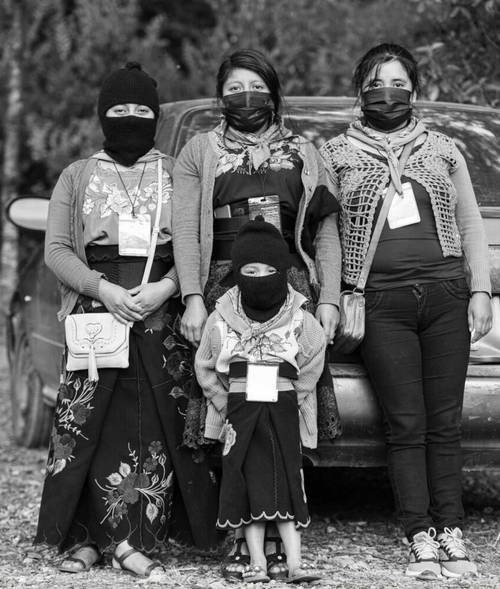

Zapatista Support Bases in CIDECI, January 2025, by Carlos Ayala CARLOS AYALA

Original text by Juan Trujillo Limones published in El Salto on March 19th, 2025.

*Juan Trujillo Limones is a Mexican anthropologist and journalist. He has conducted several investigations on Chiapas and is a contributor to the Mexican magazine Ojarasca.

Translation by Schools for Chiapas.