Reflections on the One-Year Anniversary of the UCLA Palestine Solidarity Encampment

By a militant organizer from the UCLA encampment with assistance from outside agitators.

Download a zine version to print/fold here.

Due to the violence and fierce collective self-defense that characterized the action, the UCLA Palestine Solidarity encampment became one of the major sparks and infamous stories of the 2024 “Student Intifada.” There are many political lessons to be learned from the student intifada, both from the height of its militancy and from the counterinsurgency which took hold soon after. This counterinsurgency contains many parallels to the containment of resistance after the George Floyd uprisings, with contradictions heightened by the limitations of a student-centered movement. My hope with this anniversary reflection is to keep the memory of militancy alive while also critiquing how it has been erased or misrepresented, and to close with suggestions on how we proceed from these lessons. What follows is not a well-known story.

Many reflections on the UCLA encampment (April 25–May 2nd 2024) prefer to dwell on the victimhood of the students, and the failure of the UC administration to protect these victims and the beautiful community they created. These analyses reflect a severely defanged tendency that effectively demobilized the student movement and mired it in self-congratulating and self-infantilizing narratives. The militant resistance of the camp is rarely uplifted because it contradicts the image of non-threatening peaceful protesters.

We were not victims or heroes; we were a militant, confrontational force of students and community members committed to risking and sacrificing in solidarity with Palestine. Due to the unique conditions at UCLA, where violent Zionists attempted to physically assault students from day one, everyone was quickly forced to see the necessity of self-defense and the need for a highly organized and robust security team that took on round the clock shifts. People were forced to deprioritize personal comfort, safety, and ego, practice self-control and yes, follow rules, much to the chagrin of those who fetishize the freedom of individualism. Militancy was pushed and nurtured by leadership that treated the encampment like the war zone it was, and discipline was collectively strengthened by the practical concerns that we had to face every day to preserve the camp, like instituting quiet hours so folks could recharge to fight the next day. The standoff against the pigs was made possible by the resilience, training, and discipline built after a week of warding off Zionist attacks on the barricades.

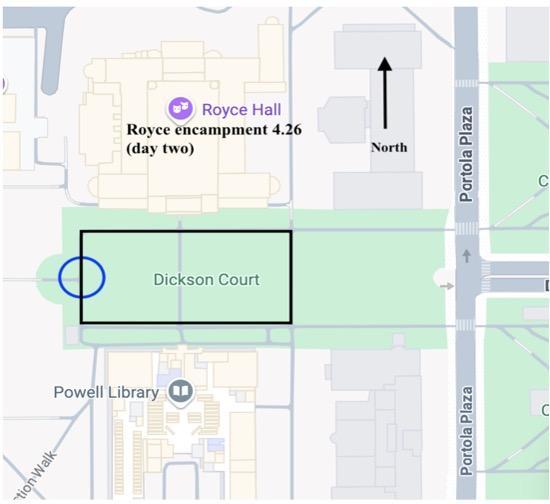

We chose a strategic hilltop location to avoid taking the low ground beneath Zionists and police, both of whom attacked us with projectiles. In the 48 hours prior to the morning of 4/25/24, when we crept onto Royce Quad to set up, organizers amassed a large quantity of scrap wood and pallets to assemble barricades immediately. The encampment required a logistics team for food, water, barricades, and medical supplies, a medic team to administer care, a media team to interface with journalists, and a security team to prevent the university, the police, and local fascists from harming the community. This reflection centers on the effort to maintain a militant, disciplined movement in the face of external and internal pressures.

Those who stood on the frontlines of the Royce Encampment at UCLA remember the power of our community as we broke the line of the Zionist attackers and drove them away from our barricades three nights in a row. We remember how the Zionists fled. We remember the fear in the eyes of 30 LAPD officers when we kettled them and drove them from the encampment. And we remember feeling the blossoming militant potential of a thousand people committed to our collective struggle.

Many accounts of the 6-hour police sweep have described the concussion grenades, the wounds, and the beatings. Accounts of the Zionist attack have described the bear mace and broken bones. These accounts only narrate what was done to us and the choices the pigs made, obscuring the choice that hundreds of people made that night to courageously hold ground against a militarized and aggressive police force the night after fighting off a fascist mob. Everyone knows about the rubber bullets. Do people know that one encampment defender was shot in the knee, and after being bandaged and encouraged to rest, went straight back to the frontline because he had been shot by the IOF as a child and this “was nothing in comparison?” Do people know that countless comrades who were bear maced on the night of the Zionist attack went to the medics to get their eyes flushed, went back to the frontline, and did this for multiple rounds? Do people know that we drove off all three major Zionist attacks by advancing our line against them, in unison, forcing them to panic and flee? Is anyone aware of the defeats, humiliations, and injuries Zionists sustained in their failed attempts to destroy the camp? Was the sweep a brutalization or was it a battle? That night, a collective of people who had been radicalized by the necessity of militant defense against Zionists became soldiers.

We are at war– against the university, against the Zionist entity, against global imperialism, and against the infrastructure of genocide. If we don’t maintain a clear militant line of needing to fight the police, rather than expecting their protection, then we risk losing the political clarity behind what an anti-imperialist movement in the imperial core requires. The struggle against imperial violence abroad is always a struggle against domestic warfare at home, especially given the influence of the military on American police forces.

A year later, as memorialization and celebrations of the student intifada proliferate and atrocities continue in Gaza, it is our duty to critique not only the encampment itself but also how people have chosen to characterize and remember it. How did we get there? What made it possible? Where have we gone since? It is worth quoting recently exiled student organizer Ziyan Mataora, who shares much with my analysis:

“We cannot recommit to the struggle without first truly and absolutely acknowledging that our movement was militant for a brief period of time — then collapsed due to internal contradictions combined with a lack of sustainable infrastructure to combat state repression, degenerating into a movement that has become largely toothless out of fear and liberal tendencies of a lack of discipline and disorganization. Despite the insistence of national organizations such as NSJP and PYM and many others in their social media campaigns, I do not think that romanticizing the student movement is acceptable, especially when we cannot name material victories in the fight for Palestine in American universities, primarily universities actually divesting from weapons manufacturers, not just symbolic victories of passing divestment resolutions.”

Spontaneity, “Leadership,” Autonomy, and Building Militancy

The UCLA encampment radicalizing to the point of fighting the pigs for 6 hours resulted from a combination of strong leadership and collective buy-in that disciplined and empowered the right people to become militants. When liberals realized the militancy of the camp had exceeded what they were comfortable with, they often left. Alienating liberals strengthens the militant potential of our movement and discourages the liberal tendencies in people who are radicalizing in real time, as it did the night we expanded our barricades.

Leadership and autonomy are not mutually exclusive, and strong militant leadership is important, especially when dealing with a large group of conflicting political visions. This type of leadership is necessary for quelling liberalism in the mostly petty bourgeois student movement, where careerism and respectability politics stifle interest in radical disruption. There were also alignments beyond just student and non-student. There was the non-direct actionist community support, mostly non-student, and often from cultural groups or organizations focused on housing, education, etc. This included local Arabs and Muslims that didn’t organize but would show up for Palestine. There was also support from autonomous anarchists and direct actionists, as well as from the progressive, non-activist student body who did not belong to any organizations or affinity groups. The makeup of encampment leads was also varied, though mostly affiliated with undergraduate and graduate Students for Justice in Palestine and the Rank-and-File Caucus for a Democratic Union, UAW 4811. Some were adults who had lived in L.A for years and had organized for even longer, with experience in direct action and connections to local non-student organizations and/or autonomous action networks. Others were much younger and receiving a crash course in confrontational action, learning and adapting quickly but susceptible to the interference of counterinsurgents and liberals.

The first day or so of the encampment internally resembled a music festival: complacent, indulgent, and with very little desire to be confrontational. People were getting high and drinking, sitting around chatting, and calling it resistance to genocide because a Palestine flag was on their tent. We quickly instituted strict no drinking or smoking rules to foster a culture of responsibility; this was not a party nor a place to have fun. The camp was a tactic of resistance, and the constant threat outside required vigilant, alert, and sober situational awareness. Zionist counter protesters began assaulting and trying to breach the encampment the first day by tearing at the barricades, stalking and attacking protestors, playing IOF torture music throughout the night (and every night that followed), rushing the barricades, brandishing knives, releasing infected mice, and more. Those who were not serious about defending the camp saw themselves out, and those who stayed despite the risks were radicalized and became heavily invested. We demarcated five zones that Zionists often tried to breach, limited entry to only two zones, and established a complex check-in, wristband, and vouching system once Zionists wearing keffiyehs began infiltrating the camp. It is a delusion to imagine that planning and implementing all this, in addition to the logistics of feeding, politically educating, and training hundreds of people each day, could happen without leadership. Some crews like the food tent, medic tent, and media team became basically autonomous while still coordinating with leaders. The negotiation between autonomy and leadership was a constant struggle, but for the most part mutual respect and a shared commitment to the camp left room for both.

Autonomy among encampment participants often did not translate into militancy, and liberals took it upon themselves to autonomously peace-police. Due to constant threats, we needed 24/7 security across most of the perimeter and a lot of manpower. De-escalation training was intended to instill a baseline level of self-control, but among the more liberal people working security, non-violence became a fetish to impose on others through peace-policing. The limits of de-escalation became apparent the very first night of 4/25, when Zionist counter protesters continued to harass protestors until individuals broke out in random and unplanned brawls to chase them away with limited success. This demonstrated that when provoked, some people would escalate against Zionists on their own in an uncoordinated fashion. The hesitancy to stray from de-escalation and enforce a more aggressive self-defense strategy was a failure of leadership to decisively harness and direct energy. However, even as leads shifted away from de-escalation in the security trainings, this did not stop the autonomous peace policing.

There is also critique necessary against the romanticization of “community” which compelled some leaders to capitulate but which also undergirds anti-leadership proponents of encampment horizontality. Not everyone is valid, not every sympathizer organically supports escalation, and the people who want to police the insurgency of our movement legitimize their counterinsurgency on the basis of democratic participation. In contexts so full of contradictions like an elite university, militant leaders must not only guard against the neutralization of rebellion but also actively convince people of the necessity to fight.

The moral superiority of peaceful protest has been entrenched in mainstream discourse by progressive politicians and celebrities, especially following the pacification of the George Floyd uprisings in 2020. By condemning rioters and uplifting the goodness of non-confrontational and peaceful protests, NGOs and mass media characterized rebellion, escalation, and anything that deviated from pacifism as being instigated by disruptive thrill seekers who endanger others. As Martin Schoots-McAlpine writes about the 2020 uprisings, “the goal of the ruling class was to separate ‘peaceful’ liberal protestors from the more radical element, both to avoid radicalization of the moderate protestors but also to isolate the radicals within the movement.” Given that the anti-police uprisings of 2020 were some of the most visible, explosive, and subsequently defanged protests in recent American history, this manufactured commitment to “good” pacifist protest influenced the fixation on peaceful protest held by the average progressive liberal in the UCLA camp. Thus, it is no surprise that an entrenched aversion to escalation and a belief in the moral superiority of de-escalation was diffuse and difficult to overcome.

Positional Warfare: Advancing the Line, Emboldening the People

Planning and spontaneity are not antithetical, and flexibility is necessary to adapt the former to the conditions of the latter. If you can’t adapt, you can’t respond. And yes, while some liberals fled the mounting culture of militancy that began to characterize the camp, others who had been fearful in the moment looked around at how we chased away the Zionists to expand our territory and their mentality began to change. This was the political education of the camp, much more so than any teach-in or reading discussion.

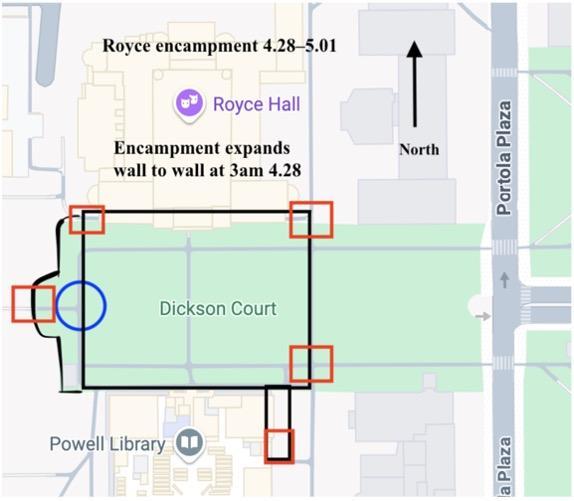

On April 28th, encampment leaders sketched a plan on how to expand the barricades since a massive Zionist mobilization to take down the encampment had been announced for the next day. The expanded perimeter would use the walls of the adjacent buildings to our advantage, limiting Zionist access to two sides when previously we had been surrounded on all sides by Zionists. This would also escalate the disruptive effect of the encampment, since Royce Hall and Powell would become non-functional for public use when absorbed into the perimeter. However, around 1 am a sizable group of counter protestors began surrounding the camp, tearing at the barricades with knives, and playing loud music while harassing and threatening protestors. A handful of leads (with only quick discussion, and not among all leads) realized it was an opportune time to expand the barricades, because the issues with a surrounded perimeter were manifesting in real time and using the barricades to push Zionists back would be an offensive maneuver to change the political tone of our camp. We assessed the strategic value, we decided to do it, we spread the word to encourage confidence over trepidation, and we picked up the barricades to advance in line formation. Caught off guard by the wood pallets and metal barricades suddenly approaching them, the Zionists panicked and scattered like cockroaches, and the encampment was secure again. Spontaneously executing our plan exposed the enemy’s cowardice, since they felt most emboldened when we were passive.

Zionists were counting on our fear, but many people had already built resilience and were more interested in improving our position than in being sitting ducks. They were starting to think like soldiers and see the encampment as territory to defend and strengthen rather than just something to sustain and enjoy. This neat and effective escalation was quickly soured by members of the encampment who feared spontaneous militancy and leaned on ideals of democratic participation to criticize the brave for acting decisively in combat without calling for a townhall or collective agreement. Courageous leadership and respect for initiative is necessary in these moments. We couldn’t afford to have a town hall for every strategic maneuver we made: when to go on lockdown, when we returned to the vouching system, how we would expel an infiltrator, how to respond to renewed and unpredictable waves of counter protesters, such as on the nights of April 29th and April 30th.

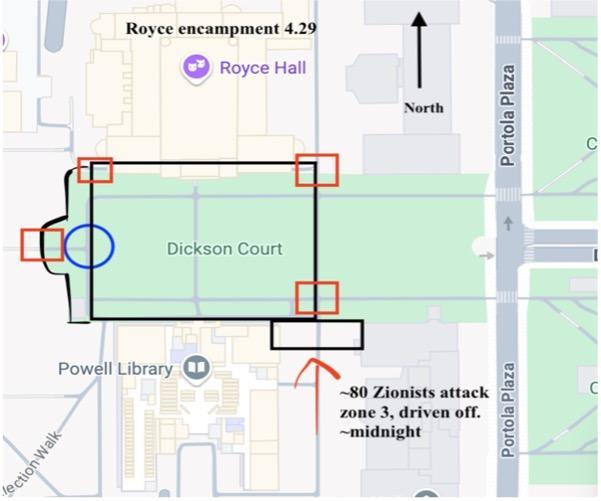

On April 29th, the night after the first expansion, a large group of counterprotesters again attempted to breach the encampment after failing to do so during the massive Zionist rally in the daytime. Once again, a lead saw a spontaneous opportunity, and after convincing the frontline security on shift that offensive advancement would successfully force out Zionists (as demonstrated by the first expansion), they pushed the attackers back about 30 feet by moving the barricades. As expected, most of the spineless agitators scattered and fled upon finding themselves on the defensive.

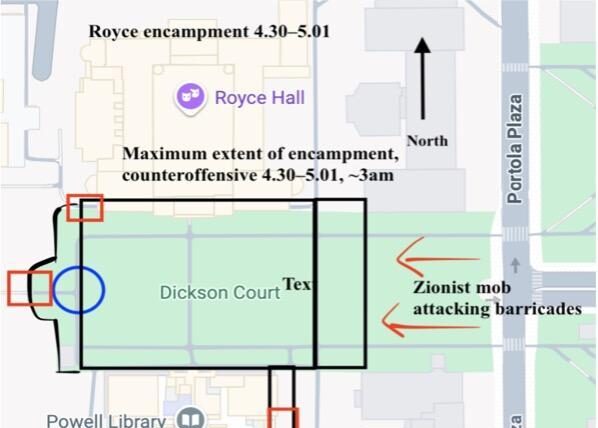

The third counteroffensive took place during the largest Zionist attack, on April 30th. The highly publicized details of this attack don’t need to be rehashed: fireworks, bear mace, beatings. Zionists failed to breach the barricades. The two prior expansions were crucial to building courage for this night; there was undoubtedly panic, confusion, and fear among the camp, but there was also a crop of people who had been previously emboldened to be confrontational and were willing to do it again. The barricades were our strength and fully remaining behind them would have been the most strategic response. At first, the autonomous “peaceful protest” ethic won out over the more militant leads, and people across the line discouraged folks from coordinating an escalation akin to the counteroffensives on the two nights prior. Without any direction or leadership, some frustrated people broke the line to fight as individuals. Abandoning the barricades to fistfight Zionists on open ground was unwise, and lead to many unnecessary injuries, but this outburst of energy reflects a boldness and bravery, which— if directed —could be highly productive.

Militant leads channeled this energy, disciplining the organic desire to resist into a more effective tactic. My comrade risked injury several times extracting impulsive people from the fascist mob to pull them back behind the barricade and prepare for an offensive. Upon establishing buy-in among the frontline to coordinate a forward push, we advanced around 40 feet and scattered the mob before pulling back to the original perimeter and demanding people stick behind the barricades. Upon failing to breach, suffering a sharp reversal with numerous injuries, and seeing fewer reckless stragglers to attack, most of the counter protestor Zionists gave up and left around 4 am.

As with almost every confrontation during the encampment, initiating and building support for disciplined, courageous, and controlled counter offensives was the essential role of militant leadership. Leaders also sought consent from everyone on the line so as to move with decisive coordination. This often required modeling confidence and pushing people to embrace the flexibility, daring, and quick decisions that our conditions required.

Leadership also solicited input from people on the front lines who proved themselves to be brave, sharp, and serious, building trust and mutual respect. The stakes were too high to compromise with liberals, entertain individualism disguised as autonomy, indulge in deliberation that stalled spontaneous militancy, or soothe the moral qualms of every person still invested in peaceful protest. If the enemy has the intent to maim and kill, passivity only serves to endanger people, break morale, and limit collective power. If one person on the line refuses to advance out of personal disagreements, they endanger their comrades to the left and right.

Beyond Free Speech – Forcing Confrontation with the Pigs

When the encampment first went up, Vice Chancellor Michael Beck informed other administrators that their goal was to “quarantine the encampment as quickly and effectively as possible, to prevent further growth.” University leadership decided to allow the tents to remain “as an expression of students’ 1st Amendment rights practices” and requested that police not yet be involved in the security plan according to UCPD police chief at the time, John Thomas. When we set up at UCLA, USC had just had their encampment swept by LAPD in 12 hours, Columbia’s repression was in all the headlines, and encampments were spreading quickly across the U.S. When a university sweeps a peaceful encampment, it sours the public perception of it as a learning institution with ethical obligations surrounding free speech. Public relations are essential instruments of counterinsurgency that reinforce the legitimacy of universities and this explains why UCLA originally elected to let the encampment stand before both protestors and Zionists began escalating. Rather than come down hard against us, UCLA chose this moment to brand itself as a tolerant university that defended free speech. Furthermore, the UC “systemwide community safety plan” advises police deployment as “a last resort” after UC Davis police set off heavy backlash and controversy upon pepper-spraying peaceful protesters in 2011. As militants we must sharpen contradictions and not allow facades of legitimacy to obfuscate our struggle; at UCLA this meant abandoning the spectacle of protest which the administration was friendly to and provoking them into open conflict with us.

One of the most prescient stalwarts of liberal counterinsurgency regarding the function of protests and police is the “right” to free speech. The liberal counterinsurgent narrative claims that the circumspect permissions of the First Amendment codified by law (that is, forms of political expression that do not break or threaten the rule of law) are the essence of “good” protest. Likewise, it is why modern policing emphasizes the necessity of friendliness and discretion towards peaceful protesters, uplifting one version of the movement and criminalizing another. In the 2022 crowd management manual for LAPD, it states that “peace officers must carefully balance the First Amendment rights and other civil liberties of individuals with the interventions required to protect public safety and property.” This is accomplished through coordinating with organizations and their protest marshals whenever possible. When principled actionists call protest marshals “peace police” it is because they are actually coordinating with police to assist in command and control. The way police are trained to respond spells it out for you in the manual- “organizers provide safety marshals to assist with protester control (“if you police yourself, we don’t have to”).” The university followed the same logic and publicly communicated its support for our “free speech.”

If we weren’t a threat to the university they would let us stay, but if we moved beyond free speech they would be forced to act. Since the administration was guarding against expansion and disruption more so than “protest” itself, the act of expanding our barricades alone served as an escalatory tactic. To do so as a form of fighting back attackers also undermined their legitimacy by demonstrating that we effectively kept each other safe through nonpeaceful methods. The UCLA encampment was not simply besieged by Zionists while we sat peacefully awaiting an inevitable sweep. We were defending ourselves and escalating in calculated steps due to the militant leadership that kept pushing the camp to be bolder. It is not victim blaming to say that we caused our confrontation with the pigs, because we are not victims. In a reflection on their 2009 occupation of Kerr Hall at UCSC, students describe this form of agency which is often erased in moral appeals to our innocence that many of us at UCLA have been subject to:

“The point is that there was nothing out of the ordinary or irrational about the way the administration or the police acted on that day. Administrators acted like administrators, and police acted like police. Anyone who was surprised or appalled by their actions seems to us naive in their understanding of the dynamics of power and resistance. The truth is that there was no ‘peaceful resolution’ to the occupation, because the occupiers refused to allow it. It was not the administration’s fault that the police were called. The outcome was forced by the students themselves.”

The Discipline to Sleep and the Courage to Fight

Around 10 pm on May 1st, less than 24 hours after the last and largest Zionist attack on the UCLA encampment, my comrade began going around with a megaphone yelling at people to quiet down and go to sleep. Chancellor Gene Block had announced that the police intended to sweep the camp at 6 pm, and indeed around 6 pm UCPD began announcing over speakers that everyone must clear out. Instead, we collected gas masks, handed out goggles and helmets, and prepared to hold our ground while the pigs slowly staged. Everyone was exhausted from the 4 hour long Zionist attack the night prior and needed to rest, especially those who had been defending the camp from relentless Zionist violence the entire week. We needed to recharge and conserve energy since the pigs clearly intended to wait us out late into the night and catch us tired. However, newer arrivals and a few other undisciplined encampment members continued to blast music, chant, and treat the camp like a party until someone came through with a megaphone telling people to take the impending sweep seriously and allow their comrades some rest before the next fight. Sometimes discipline isn’t exciting.

Before taking my couple hours of rest, I walked around to admire the graffiti concentrated under the arches of Royce Hall, feeling both calm and restless. Earlier around 6 pm the camp had been buzzing with anticipation and energy as people donned helmets and called their friends to come support. I was under no illusion that we could hold the camp forever- the question was how hard we would fight to make it as difficult as possible for the pigs. All the work to maintain, defend and expand the camp had led to this moment. I had watched people literally transform day after day through struggle, and Royce had also transformed into a collage with political messages telling cops, settlers, and Israel to fuck off. A drawing of a burning cop car on the wall with “COPS OUT OF UNIVERSITIES WORLDWIDE” neighbored messages of love to Gaza, embodying what tonight would bring. I took a picture of “Viva Viva, Tortuguita,” a slogan honoring the forest defender Tortuguita from the Stop Cop City movement who had been murdered by Georgia state troopers the year prior. Our enemy was clear.

At 1 am the battle truly begins. Community members from all over Los Angeles are still flooding into Westwood to support the camp defense while pigs deploy stun grenades over our heads. Clusters of protestors armed with shields have taken position at each zone, but I can see people who are clearly infiltrators running around yelling that cops are breaching at other areas, causing people to leave their positions and create gaps in our defense. The one I catch and confront denies everything, so I go around to each zone to warn of the infiltrators and remind people of the discipline we’ve been practicing- hold the line, move together with intention, and be brave. As pigs armed to the teeth start pressing in from different directions the screaming intensifies but no one moves an inch. The screams aren’t afraid, they’re outraged, and the courage to hold our ground is so strong that the pigs cannot advance and so they begin picking people off. The line doesn’t weaken—when someone falls or is violently yanked by a pig, another picks up their shield.

Eventually at around 2 am the pigs breach not by force but because of one disjointed line with poor communication. However, those inside quickly reappropriate barricades as shields to form a quasi-barricade enclosing the pigs and preventing further advance. Supporters outside the encampment make it difficult for more cops to follow the first contingent, and energy builds as it becomes clear that the pigs are kettled by protestors who vastly outnumber them. Our enemy was clear. We yell with hatred at these defenders of genocide and capital, and the frontline takes initiative to push forward with their new barricades. I am a few lines from the front and stand on tiptoe to watch the pigs swivel their heads around at the angry and fearless crowd surrounding them. As they begin nervously stepping back while pointing their “less lethal” firearms at us, I too began to scream from joy mixed with hate. Slowly and methodically, we push, they are forced to retreat, and as they file out of the encampment with tails tucked between their legs the fervor reaches a new level. When the last pig leaves and the perimeter closes behind him the curses turn to cheers, and though I know the long battle is just beginning I look at the strangers around me and feel I could cry. To have experienced that concentrated collective power and triumph remains one of the best moments of my life.

We fought until the sky began to lighten. A particularly difficult zone to defend sandwiched between hedges falls and the pigs rush in after the 6-hour standoff. We are mostly able to quickly retreat, but a group is surrounded and begins facing mass arrest. My nerves are racked but I am not tired at all, and I immediately go with a comrade to pick up food for jail support.

Why Would the Police Protect Us When We are at War with the Police?

When sympathetic narratives critique how police “did nothing” or say the school “failed its students” and simply stood by throughout the Zionist attacks, it is objectively true, but it assumes that the legitimate function of police is to protect people and that the university is made legitimate by serving and protecting its population (just like police). The problem with the pigs both structurally and on the major Zionist attack on April 30th is not that they failed to “protect and serve.” The police were in fact doing their job, because the only thing they protect is capital. We oppose police not purely because of what they do, but because of who they are and their social role in enforcing existing conditions of exploitation and war profiteering. What they do is always already conditioned by this structural function, whether they shoot rubber bullets into a crowd of students, harass unhoused people in Westwood, or present a friendly face through community policing programs.

“Doing nothing” in response to non-threatening protests is a strategy which strengthens the claim that pigs preserve both public safety and free speech. When we insist that the issue is pigs failing to protect students by “doing nothing,” we validate the idea that police can do “right” when they effectively protect students. The police refer to themselves as protectors of the peace for a reason, and when we fetishize peace and safety in ways that align with how police represent themselves, we do the work of reaffirming legitimacy for them. The other side of the “cops did nothing” reaction to the encampment is the emphasis on administration “failing” students. The same analysis of counterinsurgency also applies to the university and its administration, who likewise claim to protect and serve the UCLA “community” of students, faculty, and employees.

The recuperation of legitimacy by community policing programs often relies on the precarity and poverty of target populations by publicly funding scholarships, social services, housing initiatives, and other resources to win trust and support among communities most affected by policing. UCLA does much of this work. These efforts to re-establish legitimacy became federal policing policy in response to LA riots against the police beating of Rodney King. In the context of a university campus where the university already provides social services, and the precarity of the overall student body is much less dire, the remaining safeguard to legitimacy that police can employ is “de-escalation.”

By now most leftists are aware of the militarization of police and the ‘deadly exchange’ between the IOF and U.S pigs, as well as between military and police tactics, training, and equipment more broadly. It is a key aspect of why one of the encampment demands included cops off campus. In the case of UCLA, there is also thorough evidence that police were coordinating directly with Zionist security group Magen Am, composed largely of former IOF war criminals, to respond to the Royce encampment. For these reasons, it is crucial that critique of pigs is rooted in clarity on how they domestically apply martial strategy.

The militarization of police goes beyond weapons and includes the domestic application of military theories of counterinsurgency. The U.S Army Counterinsurgency Field Manual 3-24 defines counterinsurgency as a style of warfare that combines direct coercion with subtle legitimacy-building activities that keep peace and build trust. This approach leads with the awareness that conditions of insurgency undermine legitimacy and that legitimacy is necessary to stabilize rule during and beyond moments of crisis. Therefore, analysis of policing, repression, and power in our movement must emphasize the political and material warfare between insurgency and counterinsurgency rather than the abstract preservation of safety, protection, and rights. These liberal abstractions legitimize the ‘normal’ function of police and distort the narrative of how and why we fight the pigs. The militancy of the UCLA encampment attacked the legitimacy of policing, and it is imperative that we avoid narratively reinstalling this legitimacy when possible. As Kristian Williams writes in his work on the “softer” sides of counterinsurgent policing, “The state understands that there is a war underway. It is time that the left learns to see it.”

A Brief Note on Media Strategy, Legal Strategy, and Ideological Clarity

Mainstream accounts describe the experience and aftermath of the encampment as being “like a warzone” to express shock and outrage. Every sympathetic journalist, faculty person, and media-trained camp participant repeated the line of “peaceful protest” to emphasize the brutality of the police during the sweep. Media strategy has a different function and orientation in a movement than ideological line or political education, and there was some value in publicly describing ourselves like this in mainstream outlets to gain popular support. But it is concerning how many organizers have muddled key political principles by decrying how police “did nothing” when Zionists attacked and by accusing the university of “failing its students.” We might describe our movement in different ways according to different audiences, but we should never describe our opponents in a way that upholds their legitimacy.

Of course, certain strategies of the movement like lawsuits must preserve the logic of certain narratives in order to make a coherent claim. If a movement lawyer is attempting to contribute to movement defense by filing a lawsuit against our enemies, then of course the basis of the argument is based on the legitimacy of law! At UCLA, the lawsuit filed on behalf of protestors injured by Zionists and cops is based on discrimination and negligence, constantly appealing to the peaceful, lawful protest, and victimhood of protestors in order to seek redress for them. As organizers we know that the police are the armed force of the same law which a lawsuit appeals to, but all the internal contradictions of this portion of movement work should not be muddled with our principled political analysis and propaganda. Legal advice is not political advice, and so legal narrative should not be political narrative. Movement lawyering serves an organizing purpose, but a purpose that does not include building militancy. That being said, the lawsuit narrative of expecting protection and decrying mistreatment cannot define our own perspective, nor should it dictate our path.

A Movement with Teeth

Many intellectuals and first-hand accounts have emphasized how the encampment was an experiment in living, a rehearsal of freedom, and a manifestation of the collective joy that comes from mutual aid and solidarity. While none of this is inherently wrong and while there may be political value in pointing out how we are able to take care of each other, the purpose of the encampments was never to indulge in new social models. The purpose was to cost the university money, to physically disrupt, and to express mass oppositional power. To that end I would emphasize, explicitly and repeatedly, that the most liberating and radicalizing part of the UCLA encampment was fighting the Zionists and police. The most important experience was sacrificing personal safety to defend something greater than yourself, and that is not always a joyful experience. In fact, it was often exhausting, frustrating, and sometimes frightening.

It was more important that the largely privileged, comfortable, and politically complacent student body receive blows from police while refusing to surrender than it was for this population to have interfaith seders and engage in collective study. We are at war with imperialism, and romanticizing the encampment for its internal dynamics slips into a liberal metaphysics of resistance. On the night of the sweep, there were three groups of LASD personnel with snipers and tear gas guns on the roof of Royce Hall. That is what we are up against, and “taking care of each other” in a beautiful display of mutualistic living has no teeth or tactic against that. Instead, what we do have are the barricades, the helmets, the resolute commitment to never surrendering. Non-militants speak of the encampment as though its political value stems from getting people to live and sleep together. If that was the purpose, we could’ve started a hippie commune anywhere.

Our current political moment requires courage, discipline, and clarity. With the collapse of the so-called ceasefire in Gaza, the genocide against Palestinians rages on and we must commit to making our struggle against it meaningful. What does militancy look like in the context of overt fascism intensifying in the U.S, among ICE disappearances and heightened lawfare? How should the student movement for Palestine proceed in the wake of the student intifada, when political prisoners like Casey Goonan lack widespread support and have been abandoned? In my personal correspondence with Casey, they wrote me, “I remain steadfast and unbroken in here, and it’s the Palestinian resistance and such spirit that keeps me going, reminders of our obligation to destroying empire from within.” The repression we’ve faced at UCLA since the encampment has been used by many to justify passivity, cowardice, and inaction. It is past time we remember our obligation and stop acting like victims.

Increased policing, surveillance, and repression necessitates community defense efforts and collective bravery; anything less will not suffice. When the pigs knock on our doors, or when ICE prepares to launch a raid into university housing, we mustn’t indulge in any fearful demobilizing tendencies which the student movement has suffered since last spring and which squandered the militancy of the encampments. Kristian Williams aptly writes that “when facing counterinsurgency, we need to learn to think like insurgents: The antidote to repression is, simply put, more resistance. But this cannot just be a matter of escalating tactics or increasing militancy. Crucially, it has to involve broadening the movement’s base of support.” Realistically, the militancy across campuses is not at the height that it was in the spring of ’24 and sloppy escalations won’t solve this. Instead, we must prove to more and more people as we did in the pressure cooker of the UCLA encampment that we keep us safe. Zionists at the barricades, ICE at the door- we must build mass confrontational power to fight back against fascists. We must sharpen the teeth of our movement and proceed with militant discipline.

Download a zine version to print/fold here: