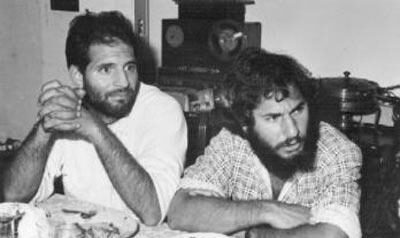

Monte Melkonian was an US-born Armenian revolutionary who struggled for the liberation of his land from Turkish occupation from the late 80’s until the Nagorno-Karabach war against Azerbaijan where he fell martyr in 1993. The struggle for the Armenian cause brought Monte to Lebanon where he joined the ranks of ASALA (Armenian secret army for the liberation of Armenia) in the late 80’s. There, he, together with other Armenians, Kurds, Arabs and Turkish fighters took part in the resistance against the Israeli invasion of the South-Lebanon. For some time his brother Markar joined him in Lebanon in the Palestinian resistance. On the base of his own memories and the ones reported in Monte’s self-biography “A self-Criticism”, Markar wrote the book “My brother’s road”.

The book includes a passage where he speaks about the PKK cadres he met at the PLO military camp in the Beka’a valley, talking about their approach, both among themselves and with the others militants. We decided to share this witness-report, which allows to understand how the PKK, from the very beginning, developed in a deeply internationalist context shaped by the cooperation between communist, socialist and national liberation movements against the hegemonic forces. In his description we find one of the mayor reasons for the success of the PKK: Militancy, discipline and an absolute insistence on their values and living by them. Exactly in this period 11 cadres of the PKK fell martyr in Lebanon fighting the Zionist aggression.

“Many of the trainees at the Struggle Front camp were shibl, or “cubs,” in their teens. Some of them had literally run through the desert and crossed the Syrian border a few hundred meters east of the camp, to flee Syrian President Hafez al-Assad’s crackdown against the Muslim Brotherhood in Syria that summer. The older trainees consisted of Arabs and Armenians, mostly from Syria, Lebanon, and Palestine. There were six Kurdish cadres, too, from Abdullah Ocalan’s PKK. At night, the Kurds actually dreamt about their suffering motherland, and as soon as they awoke they charged off to the drill ground. They dug foxholes with gusto and shouted Thaura! Thaura! “Revolution!” during assault practice, instead of the usual Allahu Akbar! “God is Great!” Whethey picked the odd quince, they left coins for the farmer at the foot of the tree, and when a Druze farmer came to harvest olives at a nearby orchard they climbed the trees with buckets to help. Once, when the Kurd Suleiman broke a banana in half and absent-mindedly handed Comrade Hassan the smaller of the two pieces, his PKK comrade Terjuman demanded a round of criticism and self-criticism. Suleiman came clean with a self-criticism and a solemn oath never again to engage in such unseemly behavior. After their initial amusement wore off, the scruffy, swearing, cigarette-smoking Arabs and Armenians at the camp began to feel self-conscious in the presence of the abstemious Kurds, with their internationalist songs, their allusions to German classical philosophy, and their constant focus on revolution. But Monte loved these goings-on. “These guys are like gold!” he effused. Their enthusiasm was contagious. One by one, the smokers started tossing aside their cigarette rations after returning from the morning jog. All the comrades grimly huddled around the radio for news about the September 12, 1980 military coup in Turkey. Arab recruits volunteered to shoot Turkish diplomats. Before long, they were all stomping shoulder to shoulder under the sun, shouting in Arabic, Kurdish, and Armenian: “Return to the homeland!” “Struggle until victory!” and “We are fedayees!” At Yanta, Monte felt that expansive feeling that comes with living and fighting together for a common purpose. It was a feeling for which the word “solidarity” is entirely too tepid. The simplest activities— squatting around a tray of lentils; tearing bread and handing it out; donating blood; passing the overcoat at the change of the guard—each of these gestures formed part of a daily liturgy that had nothing to do with egoism or altruism.”

The struggle for Armenia and Kurdistan liberation has always been deeply intertwined, although within the national liberation paradigm they have taken different strategic lines. In the 1980 conference held in Sidon, Lebanon, ASALA and the PKK announced that they were fighting together against Turkish state occupation and trained together in PLO camps in Lebanon until 1983.

ASALA went through a complex process of deviation from the revolutionary line that had several consequences: the split of the organization between the faction of the bloodthirsty founder Hagop Hagopian and the Melkonian faction, the rupture of relations between Hagopian and the PLO, and numerous reprisal murders against dissident militants ordered by him. The Melkonian’s struggle then continued uninterrupted even during the critical moment of the fall of real socialism, a phase in which, arguably for Kurdistan, the question of the future of both nations and their revolutionary struggle in the new world order arises forcefully. In Melkonian’s understanding, the Kurdish and Armenian peoples, who share the burden of colonization and genocide on the same land, also share the duty of common liberation. He has always shown a very critical and broad approach to this issue. With his stance he marked a different line from the one of many nationalist militants and Armenian intellectual figures who never really accepted the idea of common struggle because of the involvement of various Kurdish tribal elites in the 1915 Armenian genocide. With the same attitude, he harshly criticized the violence, carried out as a form of historical revenge, that Armenian troops (many of them under his command) committed against the Kurds living in the Nagorno-Karabakh territory during the 1993 war against Azerbaijan.

Melkonians reflections from his book “A self-ctiticism,” on the meaning of the holy-day “Newroz” precisely reflect his internationalist position and his attempt to understand the struggle of the PKK and the Kurdish people in a right way.

“NEWROZ: A NEW STAR

Every year, on March 21, the Kurdish people celebrate their holiday. This is one of the most important and ancient of dates on the Kurdish calendar. The Kurds call it Newroz or “the new day”. The exact origin of Newroz is uncertain, but the tradition is traced back to the fall of the Neo-Assyrian capital, Niniveh in 612 B.C. For many tribes of the Jazira; the defeat and burning of Ninive represented the overthrown of a despotic; oppressive regime. This defeat marked a new era for the people previously dominated by the Assyrians. Among the people to celebrate the new era were the predecessor of modern Kurdish nation. For over 2500 years Newroz has been celebrates by building bonfire which give light through the night, separating winter and spring. The date is festive, with dancing and feasting. Our main concern of course is not ancient history. What concerns Armenian militants is the significance of Newroz for our Kurdish comrades today. How has Newroz as an important festival, and why has it gained so much emphasis in recent years? In Answering this question we may learn a lesson which is internationally valid. The Symbolism of Newroz is clear: the end of winter and the start of spring; departure from the old and welcoming the new; the end of an oppressive regime and the beginning of a new era. Newroz, in short, signifies a new start. This is why Newroz has survived, and why it is so very important today. The Kurdish people today are struggling for their national self-determination. They are struggling to cut the feudal bonds of the past and establish a democratic socialist and revolutionary Kurdistan. They are for something new, something better than anything that has occurred in the past. Their struggle is for progress, for future. This is a simple but powerful lesson which has a such meaning for Armenians as for Kurds. The Armenian people are also at the stage of leaving behind old ideas and institutions. We are replacing counterproductive ideologies with new approaches for the problems we face. We are taking a step forward, toward the goal which, if achieved will results in conditions for Armenian people better than any yet have been existed for three thousand years. We are not struggling for military domination of land or for an imperialistic-controlled “Armenian regime”. We are struggling for the liberation of our homeland from the domination of imperialism. In this struggle, we are no longer alone. Alongside us there are our Kurdish compatriots, our Turkish comrades and all peoples struggling for their freedom and national rights. It is truly the dawn of a new day, a Newroz. We have the right to celebrate, to be festive. We have started now.”

22 December 1985, Fresnes prison, France.

Monte Melkonian

Like Melkonian, we can, by learning about our respective struggles and giving meaning to our history find similarities and differences that will enrich our common vision for a socialist life. In order to develop common struggles and strengthen each other we need to dive into each others realities and find the core of humanity in our shared values.

On the day of Monte Melkonian’s martyrdom we remember his great struggle for the Freedom of the Armenian people and his efforts for developing an internationalist approach and understanding that overcomes the disease of Nationalism which has caused so much division among Revolutionaries. As he said: “In this struggle, we are no longer alone. Alongside us there are our Kurdish compatriots, our Turkish comrades and all peoples struggling for their freedom and national rights.”