As I continue to endure worsening complications from prostate cancer and am denied treatment by U.S. prison officials, which has gone on for over a year, I’m reminded of Frantz Fanon’s own death from leukemia and how the U.S. government provided him care at the very end.

Fanon a champion of national liberation

Fanon was one of the world’s leading champions of national liberation struggle during the 1960s. Just months before his death, he wrote what many regard as the “bible” of anti-colonial resistance, “The Wretched of the Earth.” (1)

Born in Martinique and trained as a psychiatrist, Fanon joined and lent his expertise to the Algerian resistance against French colonialism. His writings and example influenced revolutionary movements all over the world and such leaders here in Amerika as Huey P. Newton and the original Black Panther Party, Malcolm X, George Jackson, Imiri Baraka, James Yaki Saykes and a great many others.

He died in Washington, D.C., on Dec 6, 1961, at the National Institute of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, where he gained admission and treatment through involvement of the CIA. He didn’t favor receiving treatment “in that country of lynchers,” but was told by advisors that treatment at this institution was his only path to survival. He distrusted the medical staff and insisted as he lay dying that “they put me through the washing machine last night.”

Treating Fanon as a PR tool for Amerika’s ambitions in Afrika

Whether Amerika truly tried to save Fanon’s life or not, the offer of treatment was a political bone thrown to the Afrikan liberation struggles and the new Black leaders of the newly emerging Afrikan-led nations, as their European colonizers were withdrawing and being expelled from the Continent because of Afrikan resistance.

Amerika was portraying itself as a champion of Afrikan national liberation, with a self-serving ulterior motive, of course. The angle was to push the European colonial powers out and take their place in accessing and controlling the Continent’s abundant natural resources, especially its vast fossil fuel reserves.

To accomplish this, Amerika aspired to prop up and back Black Afrikan rulers to take control of the liberation movements and “liberated” Afrikan countries and serve as its puppets and junior partners in stealing and exporting Afrika’s resources. This was the very neocolonial method that the U.S. had used for over a century with great effect in its own “region of influence” of Central and South America.

In 1957, then-Vice President Richard Nixon exposed these ambitions upon returning from a tour of Afrika. He stated:

“American interests in the future are so great as to justify us in not hesitating even to assist the departure of the colonial powers from Africa. If we can win native opinion in the process, the future of America in Africa will be assured.” (2)

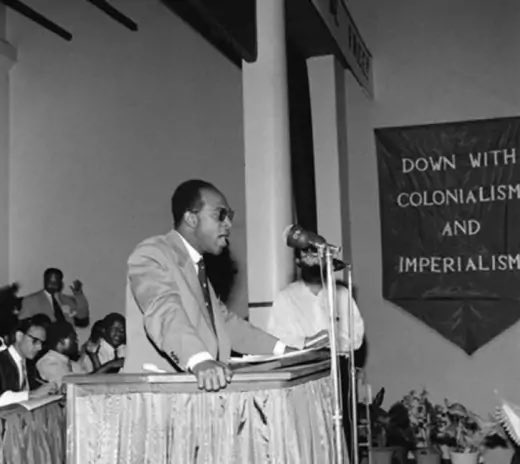

Amilcar Cabral sounds the alarm against U.S. neocolonialism

In analyzing the development of neo-colonialism in Afrika, Amilcar Cabral (one of Afrika’s great revolutionary leaders and theorists) was the first to raise suspicion of Amerika’s support of Afrika’s nationalist independence movements as a neocolonial plot and to recognize that the strategy of revolutionary nationalism did not provide an answer, but was actually a gateway, to neocolonialism. He wrote:

“In Guinea as in other countries, the implementation of imperialism by force and the presence of the colonial system considerably altered the historical conditions and aroused a response – the national liberation struggle – which is generally considered a revolutionary trend; but this is something which I think needs further examination. I should like to formulate this question: Is the national Liberation movement something which has simply emerged from within our country, is it a result of the internal contradictions created by the presence of colonialism, or are there external factors which have determined it? In fact I would even go so far as to ask whether, given the advance of socialism in the world, the national liberation movement is not an imperialist initiative. Is the juridical institution which serves as a reference for the right of all peoples to struggle to free themselves a product of the peoples who are trying to liberate themselves? Let us not forget that it was the imperialist countries who recognized the right of all people to national independence.” (3)

He recognized the inherent contradiction in imperialists like America promoting Third World independence if such struggles were really a threat to imperialism. He saw neocolonialism as the real danger. He noted, “What really interests us here is neocolonialism,” which he saw as the new form of imperialism that emerged after World War 2 to replace the old colonial system under European control, by “grant[ing] independence to the occupied countries plus ‘aid.’”

The revolutionary pan-Afrikan solution

Cabral realized that colonialism was no longer the major threat to the underdeveloped world, nor was revolutionary national liberation the solution. The real problem for Afrika was now neocolonialism and the solution for Afrikans everywhere was a revolutionary pan-Afrikan struggle that united all Afrika’s people in class struggle against imperialism. A model that was also championed by Cabral’s close friend and comrade Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana’s first Afrikan president who was overthrown in a CIA orchestrated coup the year after he wrote a definitive expose on neocolonialism. (4)

Pantherism as conceived by the Revolutionary Intercommunal Black Panther Party advances a similar strategy of revolutionary pan-Afrikan based movements under a revolutionary intercommunal party with some adjustments, aligned with traditional revolutionary national struggles led by Maoist Revolutionary Parties. (5)

But Nkrumah failed to follow through with the strategy of developing a pan-Afrikan revolutionary movement, party and army. As Cabral observed in his eulogy given at Nkrumah’s funeral, Nkrumah confided in him that he had made grievous errors in this regard and if he could begin anew he would follow a different course. As a further setback, before he could consolidate the strategy himself, Cabral was assassinated by Portuguese agents within his own party in Guinea Bissau.

Countering Amerika’s neocolonial dirty tricks

But Amerika didn’t quite succeed in its designs to win Afrikan influence and control, thanks in large part to the Soviet Union and its international media and efforts of people like Malcolm X, who traveled Afrika and the Third World, exposing Amerika’s crimes against Blacks in the U.S. – outrages not unlike the atrocities committed by the European colonizers who Afrikans were fighting to expel from the Continent. Malcolm’s efforts cost him his life at the design of the CIA.

So the plot to use Fanon’s cancer treatment as a political tool to win Afrikan favor failed. BUT it does not detract from the importance of the lesson we must take from Amerika’s use of slimy tactics like this to curry favor and manipulate oppressed peoples to look to the very source of our oppression as our friend and ally.

We should remember this when we see willing token Blacks encouraging us to support establishment politicians and political parties like the Democrats that are Imperialist bodies that have been at the core of our suffering since their founding, and Black puppets who are used to co-opt our struggles and woo us into looking at them as our ally against the very police state violence, class exploitation and white supremacy that it upholds and we are struggling to be free of.

Neo-colonialism is alive and well. And it shies away from no dirty tactic, including using medical care or neglect as a political Weapon.

Dare to Struggle Dare to Win!

All Power to the People!

___________________

Endnotes:

1. See, Frantz Fanon, “The Wretched of the Earth” (New York: Grove Press, 1963)

2. Quoted in “Dirty Works 2: The CIA in Africa,” edited by Ellen Ray et al. (Seacaucus: Lyle Stuart, Inc., 1979), p. 58

3. Amilcar Cabral, “The Politics of Struggle” (1964)

4. Kwame Nkrumah, “Neo-Colonialism the Last Stage of Imperialism” (New York: International Publishers, 1976); for Nkrumah’s outline of this strategic revolutionary pan-Afrikan struggle led by an all-Afrikan revolutionary party and People’s Army, see, Nkrumah’s “Class Struggle in Afrika” (New York: International Publishers, 1970)

5. See, Kevin “Rashid” Johnson, “On Pan Afrikanism: Part One of an Interview with Comrade Rashid by JR Valrey (Block Report Radio)” http://rashidmod.com/?p=2525

Fundraiser for an attorney to represent Rashid’s struggle for medical care

Here is the new donation link for Rashid’s legal fund: https://fundrazr.com/025tu2?ref=ab_6BrbV1

Send our brother some love and light: Kevin “Rashid” Johnson, 1007485, Sussex I, 24414 Musselwhite Dr., Waverly VA 23891.

From: SF Bayview