What distinguishes martyrs like Sheikh Izz al-Din al-Qassam is that studying their character is more than merely an exercise in reading the past. It is a reading of the present that stretches back through history in order to carry us into the future. With a figure like al-Qassam, to recount his life is to recount our own. And this is not simply because any historical reading is inevitably colored by the lens of the present. With a martyr of this caliber, death itself becomes a liar: his story continues, breaking the rules of time in the clearest proof that they are “alive, provided for” in ways we can see.

“Zionism wants to slaughter you just as the natives were slaughtered in America.”

— From al-Qassam’s speech after the 1930 execution of Atta al-Zeer, Fuad Hijazi, and Muhammad Jamjoum

Al-Qassam is one of the exceedingly rare figures in the history of anti-colonial resistance across the Global South who fought three separate European powers. He prepared men, money, and arms to battle Italian colonialism in Libya, fought the French in Syria until they sentenced him to death, and ultimately fell in combat against the British in Palestine. And if we momentarily accept the notion that the scattered zionist communities constituted a kind of “nation,” then al-Qassam essentially resisted four colonial projects. Setting aside the hazards of ahistorical comparison, it is difficult to recall another Arab figure who crossed the plains and valleys of Greater Syria to fight two empires — save perhaps the singular Khalid ibn al-Walid.

Revolution, in this sense, is the compression of time and space into an eruption that overturns an entire political, social, geographic, and economic order — those few weeks in which, as Lenin said, changes occur that would otherwise take decades.

Yet what makes al-Qassam an exemplar of what we may call the personality-as-revolution is not simply that he fired a gun at colonizers. Many people will eventually pick up arms, but true historical revolutionaries are few. Revolution, in this sense, is the compression of time and space into an eruption that overturns an entire political, social, geographic, and economic order — those few weeks in which, as Lenin said, changes occur that would otherwise take decades. When we examine al-Qassam’s life and trace its events, we reach an unavoidable conclusion: within the historical structure of the Palestinian people, his short years of struggle represent a concentrated distillation of what it will take us decades to understand.

We must liberate al-Qassam’s struggle from narrow factionalism and restore him to the broad horizon where he belongs: a symbol for all the peoples of the Arab world and beyond. Indeed, one of the most enduring waves in Arab anti-colonial history, particularly the strands most distant from class patronage, has been led by scholars and religious figures: from Abd al-Karim al-Khattabi in North Africa, to Emir Abdelkader, Omar al-Mukhtar, Ahmed Orabi, and later Ahmed Yassin, Ragheb Harb, Abbas al-Mousawi, and others.

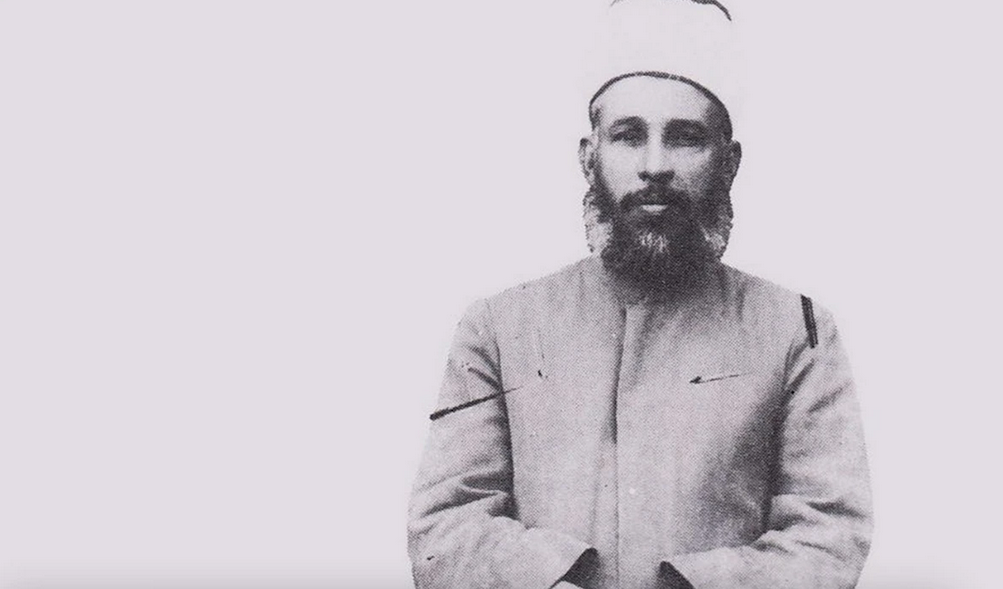

Born in 1882 in the countryside of Latakia to a modest family devoted to religious learning, al-Qassam grew up surrounded by legends, including the tale of his ancestor who split a giant snake in two. His family sent him, with the sponsorship of a local notable, to study at al-Azhar in Cairo, where he spent ten formative years under the mentorship of Muhammad Abduh, immersed in the ferment of the Arab Nahda and its vibrant intellectual milieu.

One of the earliest signs of his transformation appears upon his return to Syria, when he refused his father’s request to present himself before the notable who had sponsored his studies, rejecting the feudal hierarchy entirely.

One of the earliest signs of his transformation appears upon his return to Syria, when he refused his father’s request to present himself before the notable who had sponsored his studies, rejecting the feudal hierarchy entirely. “God did not create us as nobles and commoners,” he argued, reassuring his father: “Do not fear the notables, I am strong through my faith and through the knowledge I have learned.” Thus began a lifelong rebellion against every form of authority he encountered. From the pulpit of the Mansouri Mosque, he began preaching and teaching with such influence that he threatened the dominance of the local notables. He even barred his own mother and sisters from working in their estate, assuming financial responsibility for the household himself.

With the Italian invasion of Tripoli in 1911, al-Qassam did more than protest: he mobilized hundreds of fighters and raised funds to send them to battle. World War I found him preparing, years before the French took the Syrian coast, to resist occupation. He sold his home to purchase weapons and moved to a more defensible village. After joining the fighters of Omar al-Bitar, he battled the French in the mountains of Syria alongside national figures such as Saleh al-Ali and Ibrahim Hananu until 1920. When the revolt subsided, the French sought to co-opt or hang him; he fled to Damascus until after the martyrdom of Yusuf al-Azma at the Battle of Maysalun, then set out for Palestine via Beirut and Saida, eventually reaching Haifa.

The fifteen years al-Qassam spent in Palestine until his martyrdom in 1935 were not merely years of armed resistance shaped by his earlier experiences in Egypt and Syria. They were the period in which he constructed what we may call the revolutionary matrix: a web of relationships with every significant social force in Palestinian society. If we speak of his revolutionary compression of time and space, it is because Palestinian struggle to this day remains a long and imperfect process seeking, often unknowingly, to rediscover al-Qassam’s methodology. Indeed, the most vibrant phases of the Palestinian revolution have been those that most closely echoed his model.

“He who repeats an experiment already proven to be failure is a traitor.”

— Al-Qassam

Upon his arrival in Haifa, Qassam lived in its poorest neighborhoods, as the rest of the Syrian refugees. When the Islamic Burj School invited him to teach, he accepted and taught both boys and girls. He threw himself into education, using extracurricular activities to instill the spirit of resistance. He introduced theater to the school; one student recalled playing the role of Salah al-Din at the Battle of Hattin. His creativity earned him a strong reputation and wide affection.

This marked the beginning of his most influential phase: his speeches at Haifa’s Independence Mosque, still standing today, where he transformed the pulpit into a revolutionary platform.

He soon left the school after clashing with its administration, which prioritized profits and marginalized poor students. This marked the beginning of his most influential phase: his speeches at Haifa’s Independence Mosque, still standing today, where he transformed the pulpit into a revolutionary platform. His sermons warned against zionist immigration, calling early on for treating zionists not as guests but as enemies. His rising influence prompted repeated summons by the British and attacks from Palestinian notables who saw his popularity as a threat.

To understand the significance of al-Qassam’s mosque, one must set aside the stale Arab intellectual binary of “progressive versus reactionary.” The social hierarchy of Mandatory Palestine consisted of the British administration, zionist militias, Arab notables (whether religious or feudal elites), and last the workers and peasants. In this hierarchy, Independence Mosque, and the Sheikh who led it, occupied the most revolutionary position.

The elites, driven by their class interests, sought to accomodate the British while presenting nationalist rhetoric to the public. They attempted to limit confrontation to the zionists alone, keeping the British out of the conflict and keeping their distance from the workers and peasants who sought authentic leadership. History repeated itself as farce in later decades with the Palestinian Authority, similarly invested in class privilege, Western patrons, and suppressing the poor and the resistance.

What al-Qassam represented was the opposite: a direct bond with the popular classes, expressed through an idiom rooted in Arab and Islamic history, intuitively meaningful to ordinary people and capable of igniting national consciousness. In this historical sense, the Independence Mosque embodied genuine progressiveness, in contrast with the historical regression of the elite.

While preparing for armed struggle, al-Qassam engaged the cultural front, helping to establish the “Associations of Muslim Youth,” a largely forgotten but vital part of his project. Christian missionary societies had long served as the soft arm of imperialism, creating social environments that normalized Arab–Jewish interaction under colonial patronage. These were the predecessor of today’s foreign-funded NGOs. In 1928, after a large missionary conference in Jerusalem sparked widespread Arab denunciation, al-Qassam was elected head of the Muslim Youth Associations, which became both an ideological alternative to missionary influence and a recruiting network for his underground organization.

The enduring significance of al-Qassam’s life is that, if the Palestinian revolution is to succeed, we must all become Qassamists, each on our own front.

The enduring significance of al-Qassam’s life is that, if the Palestinian revolution is to succeed, we must all become Qassamists, each on our own front. The Palestinian hierarchy remains unchanged: American imperialism, a zionist enemy, and a Palestinian Authority built on the alliances of bourgeois families who repeat old mistakes and commit new betrayals. As George Habash echoed from al-Qassam: “US is the head of the snake.”

Perhaps the most accurate summary of Palestine’s last century is that traditional leaders of the past, and later the leaders of Oslo, empowered the zionist project at the expense of the Qassamists; the poor of Haifa’s shantytowns, the peasants of Marj Ibn Amer, and today’s impoverished camp dwellers and besieged people of Gaza. One of the most striking proofs of al-Qassam’s revolutionary insight is that he foresaw zionism’s danger earlier than anyone, recognizing that colonialism is absolute evil. Had his revolt and methodology not been betrayed, the history of Palestine, of zionism, and perhaps of the world, would have been different.

Between Nablus and Jenin, the geography of today’s armed resistance is the same terrain where Qassamists operated ninety years ago: ambushes along settler roads, homemade explosives, the same improvised metal pipes. In 1932, Qassamist fighter Ahmad al-Ghalayini built an explosive device detonated inside the room of a leading zionist settler. His operation still echoe in today’s resistance workshops in refugee camps and old city quarters. Families like the al-Saadis and al-Zubeidis, who produced fighters in al-Qassam’s time, produced them again: Zakaria Zubeidi, his brother Dawoud, and their comrades are the living continuation of the great revolutionary.

Ninety years after the martyrdom of Sheikh Izz al-Din al-Qassam, the evidence of his greatness is abundant. But perhaps the image that captures it best is this: the Sheikh ascending the steps of his small pulpit in Haifa, standing before a handful of exhausted port workers and factory laborers, and speaking words that would, a century later, form the motto of fighters who would change the world:

“It is a jihad; either victory or martyrdom.”

Moussa al-Sadah

Source: Al Akhbar