On November 25th, 1975, the 60th birthday of Chile’s CIA-installed dictator General Augusto Pinochet, high-ranking representatives of the repressive secret police forces of Argentina, Bolivia, Paraguay and Uruguay gathered in Santiago for a covert three-day summit. There, the quintet of US-sponsored Latin American fascist juntas forged an incendiary agreement. Dubbed ‘Operation Condor’ after Chile’s national bird, over the next eight years the endeavour blazed a gruesome trail of repression, torture, and murder throughout the hemisphere and beyond.

Declassified records of the summit contain little trace of the horror that was to come. They primarily outline the establishment of regular meetings between the oppressive agencies, formal and routine exchange of information, and the creation of a shared database “on people and organizations linked to subversion” in the region – in particular, individuals and entities “directly or indirectly linked to Marxism.” The only hint of belligerence is a brief snippet on the Operation being concerned with “attacking subversion related to our countries.”

Within months, Condor evolved into a transnational death squad nexus, with “subversives” the world over marked for execution. Of particular focus was the Revolutionary Coordinating Junta (JCR), an exile coalition of left-wing Latin American revolutionaries opposing the governments behind the Operation – which by 1976 also included Brazil. That July, a Condor meeting was convened, about which US intelligence learned. It was planned to insert operatives into Paris, where JCR was headquartered, to conduct intelligence gathering and ultimately, assassinations. A heavily redacted contemporary CIA memo noted:

“The basic mission of ‘Condor’ teams being sent to operate in France would be to liquidate top-level [JCR] leaders…Chile has ‘many’ (unidentified) targets in Europe…The Uruguayans also are considering targets…such as…opposition politician Wilson Ferreira Aldunate, if he should ever travel to Europe. Some leaders of Amnesty International might be selected for the target list.”

While the CIA installed all Condor’s constituent governments via military coups invariably involving mass disappearances and slaughter of political opponents, the Agency was extremely anxious about its Latin American proxies conducting “offensive action outside their own jurisdictions,” as a late July 1976 CIA memo recorded. Not least because it raised the prospect of the Agency being “wrongfully accused” of responsibility for “this type of activity.” The State Department was also intensely worried about the Operation’s extraordinarily broad range of targets.

‘Growing Problems’

A briefing dispatched to Secretary of State Henry Kissinger in August 1976 recorded how Condor’s members “see themselves as embattled” by phantom Marxist adversaries at home and abroad. “Despite near decimation of the Marxist left in Chile and Uruguay, along with accelerating progress toward that goal in Argentina,” the juntas were possessed of a “siege mentality shading into paranoia.” This was enhanced by “suspicion…the US has ‘lost its will’ to stand firm against Communism because of Vietnam,” and détente with the Soviet Union. As such:

“Fighting the absent pinkos remains a central goal of national security…Some ‘mistakes’ are made by the torturers, who have difficulty finding logical victims. Murder squads kill harmless people and petty thieves.”

In response to this illusory threat, pursuit of perceived “subversives” became absolutely central to the domestic and foreign policy of Condor governments. However, the State Department fretted how this crusade “increasingly translates into” vicious oppression of “non-violent dissent from the left and center left.” More generally, “subversion” was “never the most precise of terms.” In the Latin American context, the categorisation “has grown to include nearly anyone who opposes government policy.”

Resultantly, “there is a chance of persecution by foreign police acting on indirect, unknown information.” The memo recorded how “numerous Uruguayan refugees have been murdered in Argentina,” with “widespread” and “credible” accusations Buenos Aires was “doing their Uruguayan colleagues a favor,” and a high risk the victims were just average citizens, not engaged in political activism, let alone insurrectionary violence. Concurrently, many officials in Condor countries spoke of fighting a “Third World War” against Communism globally.

The utility of this narrative was clear. “It justifies harsh and sweeping “wartime” measures,” the State Department observed, while “[emphasising] the international and institutional aspect, thereby justifying the exercise of power beyond national borders.” Moreover, for the juntas involved in Operation Condor, “it is important to their ego, their salaries, and their equipment budgets to believe in a Third World War.” This shared self-interest was encouraging regional military governments to “[band] together in what may well become a political bloc of some cohesiveness.”

The State Department believed “the broader implications” of this development “for us and for future trends in the hemisphere” were “disturbing”, creating “a range of growing problems.” For one, Condor was damaging to the US from a public relations perspective, as “internationally, the Latin generals look like our guys.” Washington was “especially identified with Chile,” so the country serving as the Operation’s nucleus “cannot do us any good.” It was noted how Europeans “hate Pinochet & Co. with a passion that rubs off on us.”

Chile’s “black-sheep status” had “already made trouble for its economic recovery” due to overseas boycotts and countries refusing to trade with Santiago. “Human rights abuses” committed by Pinochet and his allies were constantly “creating more and more problems of conscience, law, and diplomacy.” Most gravely, “the use of bloody counterterrorism by these regimes threatens their increasing isolation from the West and the opening of deep ideological divisions among the countries of the hemisphere.” There was a significant risk of other regional governments following their lead.

Challenging this state of affairs was predicted to be problematic, given Condor members were wholly unrepentant about their reign of carnage. “They consider their counter-terrorism every bit as justified as Israeli actions against Palestinian terrorists and believe that the criticism from democracies of their war on terrorism reflects a double standard,” the State Department lamented. Nonetheless, a demarche was duly drafted, warning Condor countries of the “adverse effect” of their assassination program being publicly exposed. It was never delivered.

‘Inside Intelligence’

Orlando Letelier was one of the closest confidantes of Chilean President Salvador Allende, overthrown by Pinochet with CIA assistance in September 1973. Accordingly, he was among the first former state officials arrested by Santiago’s military government post-coup. Held in a number of concentration camps for political prisoners and tortured every step of the way, he was finally freed due to US diplomatic pressure after 12 months. Upon Letelier’s release, he was informed that DINA, the junta’s secret police force, “has long arms”. His tormentors added:

“General Pinochet will not and does not tolerate activities against his government… [punishment can be delivered] no matter where the violator lives.”

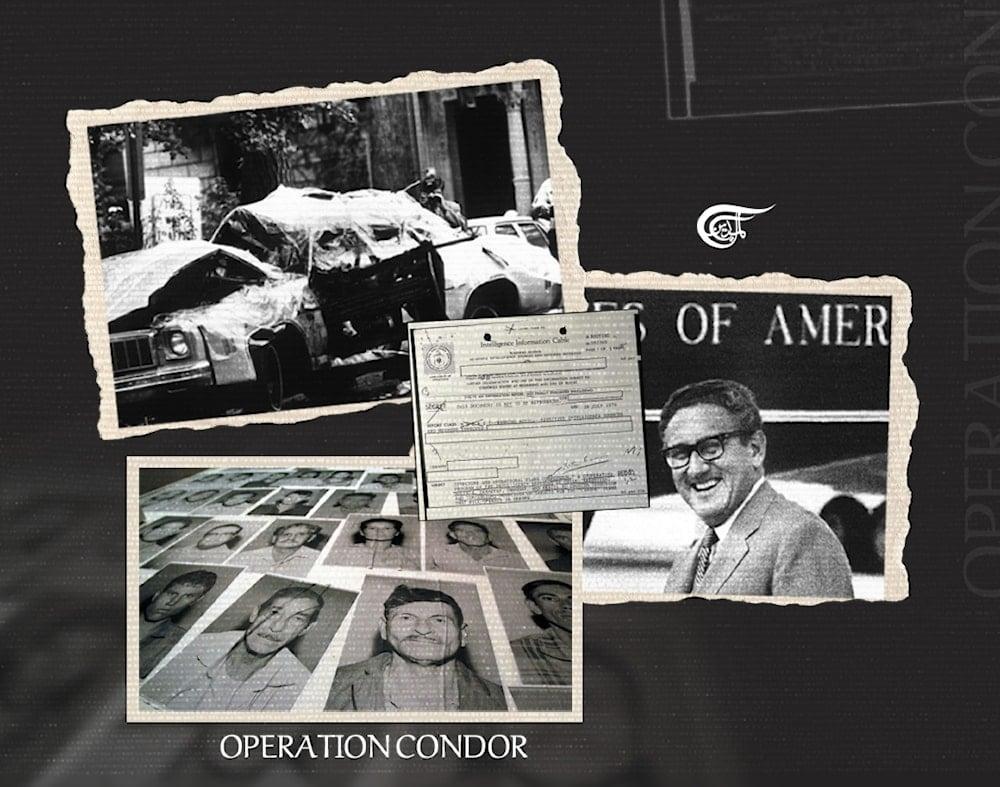

Having relocated to the US, and despite fearing for his life, Letelier immediately began organising exile opposition to Pinochet’s rule, while publicising the junta’s sadistic treatment of dissidents and opponents. His campaigning compelled several governments to sever economic ties with Chile, and refuse the country loans. These activities placed him squarely in Condor’s crosshairs. On September 21st 1976, while driving to work, Letelier was assassinated via car bomb. It was the first known act of state-sponsored terrorism to ever take place in Washington DC.

Letelier’s murder prompted a frenzy of media attention, widespread international outcry, and an FBI probe spanning multiple continents. In April 1978, Chile agreed to extradite US-born DINA agent Michael Townley, identified as the key point-person on Letelier’s slaying, Stateside. He struck a deal with prosecutors, receiving a light prison sentence and witness protection in return for offering extensive insight into how the attack was planned and executed. Townley implicated DINA chief Manuel Contreras and his deputy Pedro Espinoza as the assassination’s ultimate architects.

In a confession note authored by Townley, he detailed how “explicit orders” were given “to locate Letelier’s residence and workplace,” and meet with the CIA-created Coordination of United Revolutionary Organizations to concoct a scheme to “eliminate him” using the nerve agent sarin, “or by another hit-and-run, another accident, or ultimately by any method.” Pinochet’s government “wanted Letelier dead” by hook or by crook. Curiously, Townley also revealed Paraguayan officials told him if he “needed help” in the US, he should contact then-CIA chief Vernon Walter.

Documents unearthed by veteran journalist John Dinges suggest the CIA “had inside intelligence” about Condor assassination plans in the US, “at least two months before Letelier was killed” – “but failed to act.” Moreover, State Department cables released in 2010 indicated Henry Kissinger cancelled the dispatch of a warning against carrying out killings overseas due to be sent to Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay, five days before Letelier’s murder. There are ample indications this was no coincidence.

In September 1978, Washington demanded the extradition of DINA officials fingered by Townley to stand trial. Following an intimidatory bombing spree targeting Chile’s judiciary, Santiago refused the order. Pinochet was further encouraged by Kissinger subsequently meeting with Chilean Foreign Minister Hernan Cubillos. He dubbed President Jimmy Carter’s behaviour towards Santiago a “disgrace”, declared the extradition order’s rejection “correct”, and advocated treating Carter’s administration “with brutality.” Kissinger forecast the next US President would be a Republican, and restore relations with Chile.

So it was Ronald Reagan won the 1980 Presidential election. Chilean soldiers celebrated his victory by publicly dancing in the streets of Santiago. Condor ended after the fall of Argentina’s junta in late 1983. Still, death squad operations in Latin America targeting “subversives” only ratcheted thereafter, under CIA management. Today, we are left to ponder whether Operation Condor represented the Agency inadvertently creating a monster it couldn’t control, or was the deliberate, desired product of concerted clandestine CIA strategy, acting with Washington’s tacit approval.

Kit Klarenberg

Source: Al Mayadeen