Georges Ibrahim Abdallah is a communist, anti-imperialist, anti-Zionist, and internationalist activist born in Lebanon in 1951. To this day, Georges remains a fedayeen (a fighter), a “sin” that the capitalist system has never forgiven. Despite spending 41 years imprisoned in France, tortured and isolated, released in July 2025 and deported to Lebanon, he continues to maintain that his identity is that of a revolutionary militant: “In reality, I was a militant within the prison. I was never a prisoner aspiring to become a militant; I am a militant, and as such I fight even under exceptional conditions…”

The life of Georges Ibrahim Abdallah is the story of a young Lebanese man who joined the ranks of the Palestinian and global revolution at a very early age. It expresses the history of the Palestinian revolution in Lebanon, the revolution that began after 1967, and which, unfortunately, was cut short by a treacherous and capitulating Palestinian political leadership; but which continued with new generations of Palestinians from Gaza, the West Bank, Jerusalem, Palestine of 1948, and the diaspora. George’s story didn’t begin with his arrest in 1984, but rather long before that. The 1960s and 70s were the decades in which George’s internationalist political identity was forged. The massive mobilizations against the Vietnam War, the student and social movements of ’68, Ernesto Che Guevara’s message at the Tricontinental Conference of ’67, the national liberation struggles, and much more, converged in the militant formation of an internationalist comrade who, to this day, holds the same convictions.

The world has changed, but George Abdallah’s ideals and strength have not. He still clings to the essence of the revolutionary project of Arab liberation, which sees Palestine as its center: “The liberation of Palestine has historical and strategic value: it is the historical lever of the Arab revolution process.”

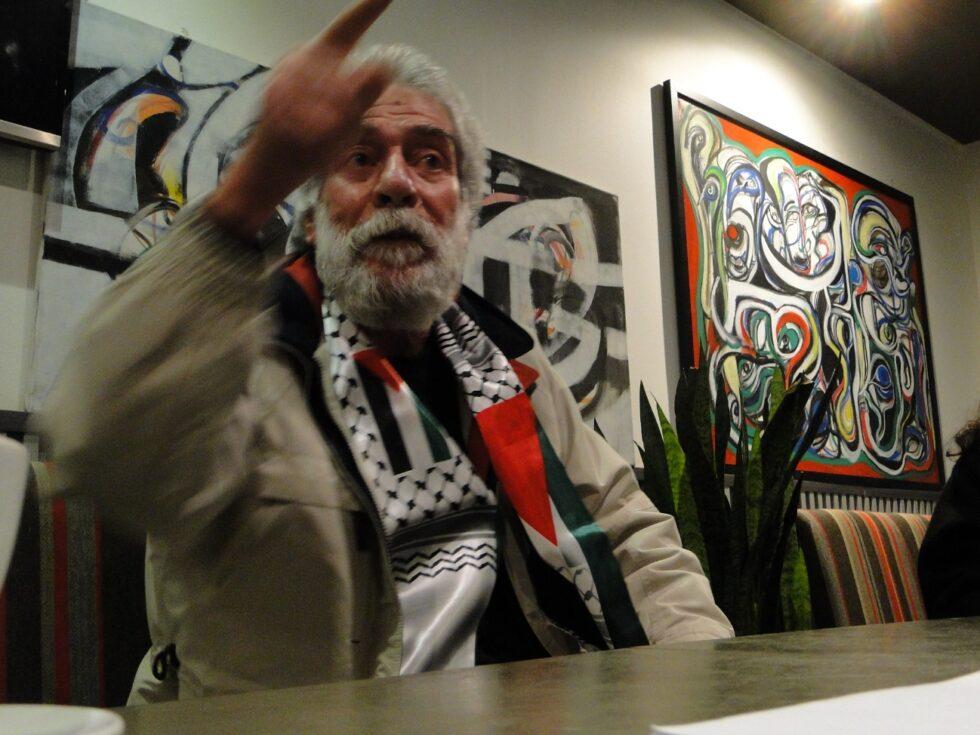

On December 18, 2025, in the city of Beirut, Lebanon, along with comrades from Masar Badil (Palestinian Alternative Revolutionary Route Movement), we were able to speak with and interview Georges Ibrahim Abdallah.

Interviewer: For us, your trajectory is an example: forty-one years in prison without your ideals being broken. How did you manage to maintain them?

Georges: Actually, I was an activist within the prison. I was never a prisoner who aspired to become an activist; I am an activist, and as such, I fight even in exceptional conditions, such as those of captivity. The central issue for me has always been the struggle; my personal situation is secondary. To the extent that my situation allows me to strengthen the struggle, I feel I am in an appropriate position. That’s how it happened.

My convictions were sustained through daily practice, alongside comrades who consistently came to support me for 41 years. Solidarity with me was understood as a means of joining the struggle alongside the Palestinian people and their masses, and also as a way of expressing the position of the Palestinian masses within the struggle in France. When workers mobilized to demand improvements in their conditions or to express political positions, those who showed solidarity with me participated directly in the mobilizations of the CGT (referring to the General Confederation of Labor of France) and other trade union organizations. I regularly—approximately every month, or every 20 or 25 days—took part in these mobilizations. At the demonstrations, some comrades took on the task of giving speeches, and thus my words, as a Palestinian and imprisoned Arab activist, were read by one of them. In this way, time passed within the context of the struggle, not apart from it.

When I was released, the court decision was based on a fundamental legal argument: that my continued imprisonment harmed national security more than my freedom. My release was granted on that basis.

My presence in prison was, therefore, a militant one. I approached captivity from the perspective of the conditions and principles of the struggle, not as an end in itself. I was not in prison to demand personal improvements, nor to demand my release, nor to proclaim my innocence. That logic is unacceptable to me.

Before the courts, I answered the central question, concerning foreign operations in France and Europe. There is no evidence to incriminate me. What I am being criticized for is my political stance. I stated that these military operations were justified and should continue, not only in France, but throughout the world, especially in the regions that constitute the heart of the imperialist system, the same system that is waging war against our people. Not only today, but since the 1980s. Today, this reality is even more profound.

Interviewer: And what about contact while you were in prison? Political news, information… what was your connection with the outside world like?

Georges: As I mentioned in my first answer, inside the prison I was an activist. Those who came to visit me were all activists. Their main task was to convey my point of view to the outside world; the second was to reinforce my position as an activist. Therefore, they made sure I had all the necessary means of access to information: journalistic, cultural, and political information. To give a simple example: I didn’t lack time because I had too much of it, but because I didn’t have enough. I didn’t suffer from having too much free time; I suffered from not having enough time to read everything I should have read. And when I say this, it’s not a literary metaphor, it’s a concrete reality.

Every week, my comrades provided me with five dossiers, just on the journalistic front. Everything published in Arabic, French, or English in Lebanon, Palestine, and Egypt. Five times a week. Each dossier was about 90 pages long. That is, around 450 pages a week, just of news material related to the Palestinian cause, the situation in Lebanon, the resistance, and the protests in Egypt. In addition, I had access to all the French press: the party press and the bourgeois press, such as Le Monde, L’Humanité, and other publications, as well as all the publications of left-wing parties, particularly the smaller ones. In that sense, I had a comprehensive view of everything available culturally and informationally, even broader than that of many people outside the prison.

As for my political training, my time was strictly organized. If you ask me how my day began: I left my cell at 8:30 a.m. and returned at 10:45 a.m. During that time, I exercised to keep my body fit for combat, so to speak.

• From 10:45 to 11:00 a.m.: washing and showering.

• From 11:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m.: reading the mail. I needed a lot of time to read the letters and materials that arrived.

• From 4:00 to 7:00 p.m.: theoretical readings.

• In the evening: correspondence related to theoretical materials and what should or should not be done.

• I slept four hours, so I woke up at 4:00 a.m.

• From 4:00 to 7:00 a.m., I answered my personal emails to preserve my humanity. I wrote simple words to my family (daughter, brother), greetings, gestures that allowed me to remain a normal human being: someone who smiles at the sight of a child, who sees beauty in a flower, who appreciates the simple things of everyday life.

At seven in the morning, the guard arrived, and the prison day officially began. Thus, my day was completely filled.

Interviewer: The situation in Lebanon, the Palestinians in the refugee camps… how did you find the Palestinians in the camps, and what is your interpretation of the political situation within them and in Lebanon itself?

Georges: The Palestinians in Lebanon are part of the Arab component of Lebanese historical identity. There is a long history of Palestinian-Lebanese struggle in Lebanon. The shared bloodshed between Palestinians and Lebanese historically constitutes the fundamental basis of our identity as activists. My generation was shaped by the effects of the Palestinian revolution and the Palestinian resistance movement. As resistance parties, Lebanese and Palestinian, we maintain a deep historical connection.

What I found in the camps confirms that Palestine remains the historical driving force of the Arab revolution. As I was saying, I am Palestinian, I am Lebanese, and I am Arab, but I am also a communist, and I see all these dynamics as part of a process that awaits the end of general exploitation.

The liberation of Palestine has historical and strategic value: it is the historical driving force of the Arab revolution. You cannot separate the two.

The camp—speaking in anthropological terms—is the space where, through its own evolution, the most intimate Palestinian identity has been formed. All of Palestine is a collection of camps. What one sees in Palestine, and what has been seen in Gaza, is a sum of camps that have shaped this profound identity of the Palestinian people. One must live in a camp, sleep for a week in one of those so-called “houses,” to understand what life is like inside. What then can be said when that life extends for decades, since 1947 and before? This allows one to understand what the camp is and why there is such imperialist, Zionist, and reactionary Arab fury aimed at destroying it. To destroy the camp is to destroy Palestinian identity.

The camp remains, to this day, a fortress impossible to eradicate. A camp is destroyed here, and the Palestinians move there and build another. A new camp cannot be created outside the framework of the destruction of the previous one.

We don’t have camps because of desertification, hunger, or unemployment. We have camps because there is an entity that swallowed the land where these people lived; their villages were destroyed, and they were forced to take refuge in camps.

And these camps weren’t destroyed just once. There isn’t a single camp in Palestine that hasn’t been destroyed more than once. That’s why the camps in Lebanon—to answer your question—have become the main refuge for the country’s poor. In reality, they are no longer “Palestinian” camps in a strictly demographic sense. If you go, for example, to Shatila, you’ll find that around 20% are Palestinians; the rest are poor people from Lebanon: Syrians, Iraqis, and Lebanese. The camp is a focal point of this historical transformation, within the objective process of the revolution, because of its real contradiction with the imperialist and Zionist strategy.

I found a people who remained steadfast, despite all their contradictions. Like any people in the world, we are not homogeneous: there are social sectors that lean toward negotiation and capitulation. But there is a vast majority of resilient masses who rose up with joy upon seeing the Israeli soldier weep and march away defeated, while the Arab regimes and armies watched passively.

We have masses who seek leaders and demand that they take a revolutionary stance. Those leaders may not be there today, but in the end, these masses will find their effective leadership, they will make the revolution, and they will become the revolutionary nucleus that will shake the entire Arab world.

What is at stake today is that Lebanon is the only place in the Arab world where a revolutionary will exists and where there is a weapon that is not completely controlled by the balance of power. Therefore, we will be subjected to enormous pressure. The entire imperialist system, all the forces linked to Israel, and in particular the Arab reactionaries, will use their entire arsenal of hatred to force us into surrender. But our people will not surrender. We will retain this weapon and be the spark that ignites those official systems that oppress our people in Egypt, Jordan, and the so-called Gulf protectorates.

That is what I found in Lebanon: vibrant forces. I was received as militants are received, and I was deeply surprised by the warmth of that welcome. I am profoundly grateful to all the leaders who received me, and I feel very reassured by the enormous willingness of the masses to give without limits.

What our people have demonstrated at this stage is that the energy of the masses surpasses all expectations. When it comes to self-defense and the future, the masses of our Arab nation, and particularly in Palestine and Lebanon, are at one of their highest points. They will play their historic role by withstanding the pressure, just as the Palestinian people historically assumed the responsibility of confronting Zionist settlement throughout the Arab Mashreq (Arab East). For decades, that burden has rested primarily on the Palestinian people. Today it falls to the Lebanese and Palestinian masses to take on the demands of this stage so that the Arab situation explodes and we can free ourselves from these tyrants, from this layer of rulers whose interests are organically linked to global capital.

Interviewer: Today many people point out that the economic and social situation is worse than it was years ago, but at the same time, voices are emerging that say there’s no need to fight, that change should be limited to the institutional level, to democratic and parliamentary reforms, without revolution. This is heard in various countries, for example, in Argentina.

Georges: On a global scale, the situation is this: we are living through explosive conditions worldwide. The movement of capital, the capitalist system as a whole, is undergoing a profound crisis, a structural crisis. This crisis is pushing the bourgeoisies to confront each other. What we see with Trump, what we see in Europe, what we see in Russia, indicates that for the third time in less than a century we are on the brink of a world war as a direct consequence of the crisis of capital. It is the third time in less than one hundred years, and this is evident to anyone who observes reality. What can we expect in this context? The masses are increasingly facing a process of fascistization on a global scale. There is a clear dynamic of transformation toward fascism within the capitalist system itself, which is progressively abandoning what it called representative democracy. Today, more and more, the main parties and governments are expressing this drift: in Argentina, in Italy, and with similar processes advancing in France, Germany, and the United States. This dynamic leads to a growing impoverishment of the masses, and this impoverishment will only worsen. The central question is this: how will revolutionary vanguards capable of uniting forces to confront fascism be formed?

In other words, the composition of today’s working class is not the same as it was in the 20th century. What are called the precarious and marginalized sectors now constitute the majority of the world’s population, distributed globally. The crisis of the capitalist system is affecting them on every continent. The question is how these popular forces can organize themselves within political frameworks equipped with a program capable of confronting fascism in Argentina, Peru, France, and elsewhere.

Our answer is clear: there is a large social mass with a vested interest in change. This mass is composed of a combination of precarious sectors, workers, and other popular sectors. This popular force is built through concrete participation in everyday struggles. In its historical process—economic, social, political, and cultural—this mass is formed amidst contradictions, but under a clear slogan: together, and only together, will we win. Together, and only together, will we advance; together, everywhere, we will prevail.

In Argentina, as in Beirut, it is necessary to identify common ground and strengthen it to build a shared identity. Solidarity with Venezuela, with Palestine, with the Kanak people of New Caledonia, with the peoples of the Caribbean, is part of the same process. It is a solidarity that forges the historical identity of the masses in the face of a global capital that offers nothing but barbarism. We have seen this barbarism in Gaza, in the West Bank, in Argentina, and in the peripheries of poverty and misery; we see it in Africa and Southeast Asia. Capital has no other proposal: only barbarism.

To the extent that we act collectively around common objectives, we contribute to building the historical identity of these masses. The masses, the agents of change, are formed through struggle, not outside of it. In the process of struggle, the conciliatory bourgeois forces are differentiated, and a common understanding of the real interests of the masses is built. These masses will come to understand their own immediate and historical interests. They will be the ones who transform reality. The role of revolutionary militants is to contribute to the construction of this popular mass on a clear foundation: together, and only together, will we win; together we fight, together we are formed. The constitution of this popular mass allows it to understand its present interests, its historical interests, and, with them, the general movement of history. That is true liberation: a liberation that occurs within this process, not apart from it.

Interviewer: The October 7 operation, the Al-Aqsa Flood… How did you experience it? Did you expect an operation of this magnitude? What were your impressions at the time, and what are they now?

Georges: I am Arab, Palestinian, and Lebanese, and I approach this issue as something that concerns every human being in this great Arab homeland. Furthermore, I am a communist, and from that perspective, I analyze this operation not only in its local dimension but also in terms of its global effects and its relation to the dynamics of the Arab and international revolutionary struggle.

From a strictly military point of view, October 7 was a relatively limited operation; it was not a large-scale operation in historical terms. The Palestinian revolution is over forty years old. That groups of fighters—a thousand or so—would carry out an action of this kind is natural, even something that could have been repeated periodically. However, what happened produced a series of effects that went far beyond what was expected.

On the political and social level, at the level of the immediate popular reaction, the response was spontaneous. Like so many other sons of our Arab people, when we saw a fedayeen capture an Israeli soldier on top of a tank, we applauded and erupted with joy. That was a natural reaction, seeing the fighters acting as fighters should. Later, when analyzing the operation in detail, it is legitimate to say that some things could have been done differently. But, in its overall direction, it was a highly successful military operation.

Now, there were effects that not everyone perceived immediately. This operation revealed a reality that was not entirely visible. When Israel faced Palestinian violence, it responded barbarically, as was to be expected. But that response transformed the entire region into an unsafe zone for global capital, and this is the crux of the matter.

To understand this, one must understand what Israel is. Until the 1970s, Israel lacked large private financial institutions: banks, insurance systems, and key financial structures remained publicly owned. In the 1980s, with the arrival of nearly a million settlers from the Soviet Union, enormous amounts of capital also flowed in, often through channels illegal from the perspective of capitalism itself. Along with this capital came a highly skilled, scientifically trained workforce, which allowed Israel to take a qualitative leap and build what is known as its “Silicon Valley.” October 7th struck this strategic core. Not because it physically destroyed it, but because capital cannot remain where there is open armed conflict. No one anticipated this effect. And it is precisely this that places Israel in the final phase of its historical existence.

The project of so-called “Greater Israel” was viable as long as this Silicon Valley functioned. It was not a classic military occupation, but rather an economic and administrative domination of the entire region, similar to that exercised over the so-called Gulf States. On October 7, that project was canceled, even if those who carried it out weren’t necessarily aware of its strategic dimension.

Furthermore, on October 7, normalization between Saudi Arabia and Israel was prevented. We mustn’t forget that Gaza is a vast prison, and that the plans involved further expanding that confinement. October 7 was the explosion of that prison, and that explosion disrupted all regional projects.

The West responded by deploying its full arsenal of barbarity and criminality, but the Palestinian people stood firm, with their wounds and their children, refusing to surrender. They offered an example of resistance that humanity had not witnessed in either Dien Bien Phu or Stalingrad. Never before had a people fought in such a way in defense of their very existence.

On a global scale, the impact was immediate. For the first time in the history of Western capitalism, a war of extermination could be observed in real time, hour by hour. Argentinians, Bolivians, and Pakistanis could see the genocide unfolding before their eyes every day. This spurred broad sectors of the youth to rise up: first out of human solidarity, then out of a deeper political understanding. This mobilization began to take on a clear character of confrontation with the “fascistization of extermination.” In a global context marked by the crisis of capitalism and the real possibility of a third world war, the Palestinian cause became a banner against the advance of fascism in Europe and the world.

That is why, when the demonstrations began in Europe and the United States, governments tried to ban and criminalize them. Wearing a keffiyeh or carrying a Palestinian flag could lead to imprisonment or accusations of antisemitism. Today, however, there is no city in the world where the Palestinian flag and the keffiyeh are not raised as symbols not only of solidarity, but also of resistance to fascism within their own countries.

Netanyahu is a concrete expression of fascism. Israel, as an entity, is an organic extension of Western imperialism, which was historically formed through wars of extermination. The United States, Latin America, Australia: all these state projects were built on mass genocide. Israel is the latest expression of that logic.

The war of extermination against the Palestinian people did not begin in Gaza; it began at the end of the 19th century. In 1948, when the Palestinian population numbered fewer than a million, they resisted. Today, they number over fourteen million. Within historic Palestine, Palestinians now outnumber the settlers. This proves that the war of extermination has failed.

On October 7th, the world told this colonial project: you have reached your end. The violence unleashed today in Gaza and Lebanon is the expression of that final chapter. Israel can no longer present itself to the peoples of the world as a “democracy.” It has revealed itself for what it is: an absolute symbol of barbarism. Without the moral and political support of the imperialist West, Israel cannot survive. They can continue sending it weapons, but weapons do not change history. It is the people who make it. And the Palestinian people, with rudimentary means, have demonstrated a strength superior to the entire military arsenal.

For more than a century, the Palestinian people have resisted a war of extermination on behalf of the entire Arab Mashreq. The colonial project targeted not only Palestine, but the entire region. And it was the Palestinian people, the vanguard of this nation, who paid the price with the blood of their children and triumphed. Today, the world tells them: you have not only resisted, you have won. And not only as a Palestinian, but as a symbol of the fight against fascism, which is advancing everywhere.

These are the historical effects of October 7th.

Interviewer: With the so-called ceasefire, we’ve seen a certain demobilization on a global scale. How do you analyze this?

Georges: What is called a “ceasefire” is a stage within this conflict, an important stage. But we must analyze its real foundations. The main backdrop is the role of the Arab reactionaries in the attempt to disarm the resistance.

The central concern that is shaking imperialism is that the armed struggle in Palestine has produced a global effect they did not expect. The fedayeen has become the representative of true humanism, the one that transformed the keffiyeh into a universal symbol of freedom and opposition to fascism. That is why they are resorting to every possible means to put an end to this form of struggle. That is, in essence, what is at stake in the so-called ceasefire. They have divided this process into three or four phases.

The first phase consists of saying, “We will allow them to eat; we haven’t managed to exterminate them.”

Then they propose a second phase: that, under religious or regional cover, the Arab reactionaries enter Gaza. But for them to enter, they demand the presence of international forces intended to disarm the so-called “terrorists.”

We say clearly: these weapons will not be disarmed. These weapons are a symbol of humanity. It is these weapons that allowed thousands upon thousands of young people to take to the streets of the world, raising the banner of freedom represented by the Palestinian keffiyeh.

If these Arab reactionaries try to enter Gaza, we will crush them. And if the imperialist forces try to enter Gaza, we will confront them and destroy them in the fullest sense of the word.

The European and global bourgeoisies, under pressure from popular mobilizations in Europe, the United States, and worldwide, have begun to make certain concessions on a discursive level. Today they tell you: you can show solidarity with the “Palestinian victim,” with the Palestinian people who are starving, murdered, and bombed. That’s allowed. But you can’t show solidarity with those who are anti-imperialist.

You can show solidarity with the victim as a victim. But for that victim to become a historical subject, a political actor, that’s not allowed: then they become a “terrorist.” You can denounce that a people is being exterminated, you can affirm that they are victims. But you don’t have the right—according to them—to show solidarity with those who are fighting with weapons to defend that people.

The imperialist forces clearly state: the real problem is that anti-imperialism is now being presented as a legitimate political position, with a real presence in the struggle. That’s what keeps them up at night.

They tell you: “You can show humanitarian solidarity with the children, with the mothers… but be careful, very careful about saying that there is an anti-imperialist resistance and that you stand in solidarity with it. That is criminal.”

That is their position. We say the opposite. These historical conditions that have made the children of Gaza a universal symbol of freedom that would not exist without October 7th. They would not be a symbol of freedom if those fedayeen who carried a bomb and placed it on a tank did not exist. Only the fedayeen position truly embodies the essence of humanism. That “humanism” that many claim to defend today is nothing other than the practical expression of the sacrifice of those fighters who put their lives and bodies on the line against the military machine.

The imperialists, in all their variations, repeat: “Show solidarity with the victims, but be careful… be careful about showing solidarity with the anti-imperialist fedayeen.”

And we respond clearly: we are anti-imperialist because we are fedayeen. And we represent true humanism because we are fedayeen who practice armed struggle, in Palestine and beyond.

Interviewer: We want you to send a message to the peoples of the world and also to Latin America.

Georges: The message to the militants of Latin America is clear: we are in the same battle. Imperialism’s greatest fear is that the anti-imperialist struggle will cease to be an abstract slogan and become a concrete reality, legitimate and embraced by the masses. That is their true fear.

“Together, and only together, we will win.” We, together with the militants of Latin America and other parts of the world. Isolated, we cannot win anywhere. If we are fragmented, none of us will win. When the masses of Latin America mobilize for their own demands under the Palestinian banner, they do so as part of the struggle against fascism. In this way, they express the most concrete and effective form of solidarity with the prisoners of the Palestinian revolution and with every Palestinian who struggles.

This principle is not just a slogan. The Argentine, Palestinian, and Egyptian masses have common interests in the face of the barbarity of capital. When the social masses in Argentina mobilize against their own fascism, they are also defending Palestine. Every victory there is a victory here. Any triumph anywhere on the planet is a victory for all of us.

Every step forward anywhere in the world strengthens the entire revolutionary force. When the sons and daughters of the Argentine people advance in their struggles, that advance is also ours. And every victory in Palestine is a victory for the peoples of Argentina, Peru, and elsewhere.

The true leadership of the popular masses must understand that our struggles must be coordinated. We must learn how to do this. Every battle in Lebanon must be considered in relation to a battle in Argentina, in Europe, or anywhere else. We must relate to each other as capital does on a global scale, but without reproducing its contradictions. “Together, and only together, we will win.” That is our motto today, tomorrow, and the day after.

This is how we build the popular masses with a historical interest in change. These masses are built here and there, and through this solidarity, what we call the revolutionary international is forged. The defense of Venezuela, the defense of Argentina, the defense of the popular masses everywhere, is one and the same defense. Every victory in Cuba, in Venezuela, in Russia, or anywhere else in the world is a collective victory.

Revolutionary leaderships must keep this in mind when defining the priorities of the struggle. Our enemy is global capital; our allies are the popular masses. The popular masses are not built outside of coordination: they are built within it, and part of their identity is born from this process. The level of development of the popular struggle is reflected in the nature of its leadership. When reformist, reactionary, or surrendered leaderships predominate, this constitutes a defeat for other peoples as well. When there are revolutionary leaderships in Palestine, this is a victory for Argentina. When there are revolutionary fighters in Argentina, this is a victory for Palestine.

This interaction is what allows us to build a global popular mass capable of ending the capitalist system, a system in permanent crisis that can only be overcome through its overthrow by organized masses. But this is not achieved with abstract speeches. The popular mass is built through the daily practice of “together, and only together, we will win.” This is how it is built in Argentina and beyond. Confronting them is our duty: in Palestine and everywhere. Every step here is a step forward there. Every step there is a step forward here. “Together, and only together, we will win.”