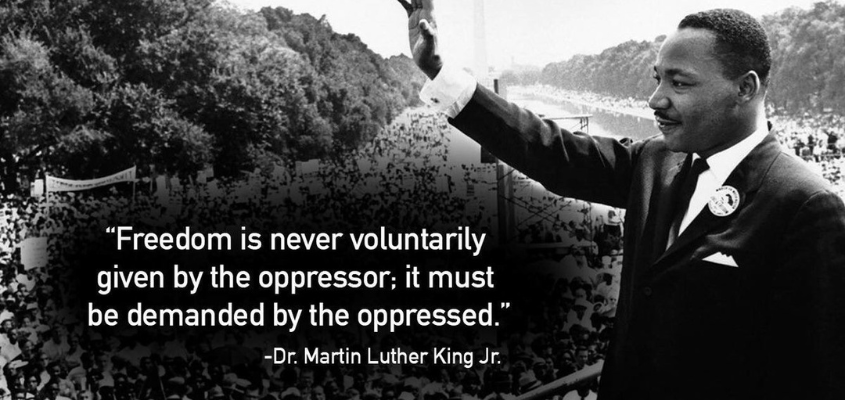

The annual ritual of sanitizing Martin Luther King Jr. serves to obscure his radical anti-war politics, which are urgently needed to challenge U.S. imperialism.

Every year in the U.S., what has emerged as a cynical ritual around the birthday of Dr. Martin Luther King takes place, where the state uplifts an image of Dr. King that is compatible with the fiction of what the U.S. society sees itself as and that depoliticizes King by ignoring his progressive Anti-war and anti-imperialist politics. But with the medieval barbarism of the Israeli genocide in Gaza fully supported by the U.S., rogue state gangsterism by the U.S. in Venezuela, and consolidating fascist terror domestically, the critique of the U.S. by someone with the moral clarity of King combined with a material analysis of the interests driving U.S. policy brings a new clarity to the normalizing horrors being carried out by the U.S. state.

The U.S. state capture of Dr. King was a part of the process of deradicalizing African Americans, an objective of the counterinsurgency and counterrevolutionary program of the U.S. settler state. That objective was to not only to neuter the radicalism of Dr. King but also to diminish the radicalism and internationalism of the Black Liberation Movement and transform the consciousness of the colonized Black population from a radical, oppositional force into a domesticated, deradicalized pro-“American” population. It would be a population that is, more “American” than African, with a psychological and emotional investment in the fiction of “America.”

But the reality of Dr. King and the movement that he personified, along with the parallel radical Black Liberation, anti-imperialist, and anti-capitalist movements, was much more complicated.

The complexity of those two movements and their intersectional politics were captured in the opposition to the Vietnam War that Dr. King publicly articulated in 1967.

But that Dr. King is much too dangerous to be a focus. This is why the official celebrations, including a celebration of his birthday, are not on his actual birthday but on the Monday after, giving the population some time off to engage in mindless consumerism with “King Day” sales

The real Dr. King, and also the real movements that emerged in the 1950s and 1960s, were less accommodating to state manipulation and distortion. King was always a fierce critic of the contradictions of U.S. life and politics. But by 1967, he felt morally charged to expand his political critique beyond domestic civil rights to address the structural violence of U.S. imperialism.

In his April 4, 1967, address at Riverside Church, King argued that the Vietnam War was not an anomaly, but a symptom of a broader system rooted in militarism, racism, and economic exploitation — what he called “the giant triplets of racism, extreme materialism, and militarism” (King, 1967). This was important because it highlighted the theoretical and practical interconnection of these elements. It located U.S. power within a global racial-capitalist order. As he noted: “A nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual death” (King, 1967). King also emphasized the humanity of those targeted by U.S. violence: “They watch as we poison their water, as we kill a million acres of their crops… so they must see Americans as strange liberators” (King, 1967).

Gaza and Venezuela: Racialized Violence, Settler-Colonial Power and Empire

The assault on Gaza exemplifies the racialized logic of imperial violence. Palestinian life is rendered disposable within dominant Western discourse, enabling extraordinary levels of civilian death to be framed as unfortunate but necessary.

King’s words regarding Vietnam apply with striking historical precision: “We have destroyed their two most cherished institutions: the family and the village” (King, 1967). Settler colonial practice has demonstrated that such violence is not episodic but structural.

Venezuela demonstrates a different modality of imperial coercion. The U.S. used unilateral economic sanctions on the country, economic warfare targeting civilian populations but justified as “nonviolent.” But the U.S. recently escalated with military violence, kidnapping the President of the Bolivarian Revolution

King condemned U.S. imperialism while arguing that it would bring imperial blowback: “The bombs in Vietnam explode at home” (King, 1967), underscoring that militarism deforms social relations everywhere. This insight into the interconnectedness of imperial and domestic power relations is almost completely absent among the contemporary left, let alone the general population. This is another product of the success of the five-decade counterrevolution – the construction of a weak, soft class collaboration social democratic left, a left that adopted analytical frameworks that prioritize critiques of “authoritarianism,” corruption, or abstract human rights violations in isolation from imperial power. This theoretical and political shift, often grounded in liberal cosmopolitanism or post–Cold War humanitarianism, treats states like Venezuela (or resistance movements) like those in Palestine as morally equivalent to imperial powers.

This produces a false symmetry that erases asymmetries of power. Such frameworks “collapse imperial relations into a flat moral universe,” rendering the United States and its targets as equally culpable, and thereby legitimizing intervention, sanctions, or regime change in the name of protecting “democracy” or “human rights.”

In this sense, sections of the left become ideologically aligned with imperial projects even when subjectively opposed to war. King anticipated this danger when he warned that the greatest obstacle to justice is not overt reactionaries but those who prefer “order” to justice and “a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice.”

Ethics, Silence, and Complicity

King’s warning that “a time comes when silence is betrayal” (King, 1967) applies not only to governments but also to intellectuals and movements. Silence about imperialism — or its theoretical minimization — becomes a form of complicity.

Knowledge and consciousness are terrains of struggle. To depoliticize empire is to normalize it. Dr. King concluded his Vietnam speech by identifying with the victims of empire: “I speak as a child of God and brother to the suffering poor of Vietnam… the barefoot peasants of our world” (King, 1967). This identification was not symbolic but political. It grounded King’s ethics in solidarity with the colonized, the exploited, and the excluded.

Contemporary radicals face a similar task. People(s)-Centered Human Rights offers a framework that reclaims human rights from state-centric, liberal, and imperial interpretations and recenters them on collective dignity, sovereignty, material survival, and self-determination. It allows movements to defend life without legitimizing empire, to oppose repression without endorsing intervention, and to build unity across the Global South and within oppressed communities in the North.

Such a framework restores the connection King insisted upon between morality and power, and between justice and structure. In a world where empire increasingly disguises itself as humanitarianism and war as protection, People(s)-Centered Human Rights provides a language for resistance that is ethical, political, and internationalist.

King warned of the “fierce urgency of now.” That urgency remains: to confront Gaza, to defend Venezuela, and to resist the normalization of imperial violence requires not only protest but theory, not only outrage but analytical clarity. Breaking the silence today means refusing both the weapons of empire and the concepts that excuse them — and standing, as King did, with the barefoot peasants of the world.

References

Baraka, A. (2017). The problem with humanitarian imperialism. Black Agenda Report.

Baraka, A. (2018). Racism, imperialism, and the politics of silence. Black Agenda Report.

Baraka, A. (2021). Sanctions are war: Venezuela and the normalization of economic warfare. Black Agenda Report.

Baraka, A. (2023). Gaza, Zionism, and the crisis of Western political morality. Black Agenda Report.

Baraka, A., & Kovalik, D. (2019). Human rights as a weapon of empire. CounterPunch.

King, M. L., Jr. (1967). Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence. Riverside Church, New York.

Said, E. (1978). Orientalism. Pantheon.

Weisbrot, M., Sachs, J., & Montecino, J. (2020). Economic sanctions as collective punishment: The case of Venezuela. Center for Economic and Policy Research.

Ajamu Baraka is an editor and contributing columnist for the Black Agenda Report. He is the Director of the North-South Project for People(s)-Centered Human Rights and serves on the Executive Committee of the U.S. Peace Council and leadership body of the U.S.-based United National Anti-War Coalition (UNAC).

source: Black Agenda Report