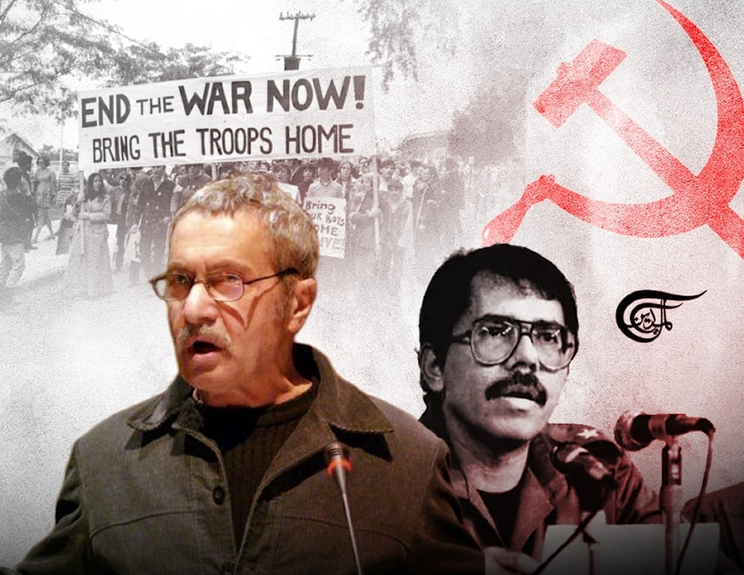

The global left is mourning the death of Michael Parenti, the influential Marxist scholar, historian, and public intellectual whose work exposed the mechanics of capitalism, imperialism, and ideological power with unmatched clarity. Parenti passed away on January 24 at the age of 92, leaving behind a body of work that shaped generations of scholars, organizers, and anti-imperialist movements across the world.

For decades, Parenti stood apart from mainstream academia and political life, refusing to dilute his analysis or bend his language to liberal respectability. He wrote not to impress institutions, but to arm people with understanding.

Working-class roots, uncompromising politics

Born in 1933 in New York City to a working-class Italian American family, Parenti often said that his political commitments were grounded not in abstraction, but in lived experience. Class was not something he discovered in theory; it was something he grew up inside.

He earned a PhD and taught political science and history, but his outspoken Marxism and anti-imperialism meant he was steadily pushed to the margins of elite academia. Rather than retreat or conform, Parenti chose independence: lecturing widely, writing prolifically, and speaking directly to union halls, community centers, activist spaces, and international audiences.

He lived modestly, avoided think-tank careers and corporate funding, and kept his private life largely out of the public eye. He was a husband and a father, including to journalist and political analyst Christian Parenti, but he never cultivated a public persona rooted in biography. What mattered to him was the work.

Exposing the class nature of “democracy”

Parenti’s most enduring academic contribution was his systematic critique of liberal democracy under capitalism. In his landmark book Democracy for the Few, first published in 1974, he argued that capitalist democracies are not neutral systems open equally to all, but class-structured states in which economic power overwhelmingly determines political outcomes.

He showed how elections, courts, media, and state institutions consistently serve the interests of capital, while popular demands are managed, diluted, or suppressed. Democracy, he argued, is tolerated only so long as it does not threaten property relations.

“Power is not evenly distributed in society,” Parenti wrote. “Those who own and control the productive wealth tend to dominate the political life of the nation.”

The book became a formative text for students and activists worldwide, prized for its clarity and refusal of liberal illusion.

Imperialism without disguise

Parenti was equally influential for his work on imperialism and US foreign policy. In books such as Against Empire and To Kill a Nation, he dismantled the idea that Western wars are motivated by humanitarian concern or democratic ideals.

Instead, he traced intervention, sanctions, and regime change to material interests: control over resources, labor, strategic territory, and global markets. He showed how human rights discourse is selectively deployed, how compliant client states are shielded from scrutiny, and how resistance is pathologized as extremism.

One of Parenti’s most quoted observations remains painfully current: “The essential function of imperialism is not to civilize or democratize, but to maintain a global system of inequality.”

His analysis helped anti-war and anti-imperialist movements reject moral distraction and focus on structure rather than spectacle.

Anti-anticommunism and historical honesty

In Blackshirts and Reds, Parenti confronted Cold War anticommunism as an ideology rather than an analysis. He did not deny repression or failure in socialist states, but he exposed how capitalist violence is normalized while socialist experiments are judged by impossible moral standards.

He insisted on historical comparison: asking why fascism is treated as an aberration while capitalism’s own mass violence, including colonialism, slavery, sanctions, structural deprivation, is rendered invisible or inevitable.

The book reopened serious discussion of socialism’s achievements in literacy, healthcare, women’s participation, and social welfare, at a time when such discussions were considered politically taboo.

Media, ideology, and manufactured consent

Long before “media literacy” became fashionable, Parenti laid bare the structural bias of corporate media. In Inventing Reality, he explained how ownership, advertising, sourcing, and elite consensus shape what is reported, how it is framed, and which voices are excluded.

He stressed that propaganda does not require overt censorship. It works through repetition, omission, ridicule, and selective outrage, teaching audiences what to ignore as much as what to believe.

This work made Parenti a cornerstone of critical media studies, especially among activists seeking to challenge war narratives and economic myths.

A scholar of struggle, not accommodation

What distinguished Parenti was not only what he argued, but how he lived. He never treated radical politics as a career ladder. He accepted marginalization rather than compromise and continued to speak plainly when euphemism was rewarded.

His lectures, many of which circulated widely online, are remembered for their warmth, humor, and devastating precision. He trusted ordinary people to grasp complex ideas without academic gatekeeping.

In doing so, Parenti helped bridge the divide between scholarship and struggle, restoring confidence in class analysis at a time when it was being hollowed out or replaced by moral abstraction.

An enduring legacy

Michael Parenti did not found a school or cultivate disciples. His influence traveled differently: through dog-eared books, shared lectures, study circles, movement spaces, and quiet moments of recognition when the world suddenly made sense.

At a time of renewed imperial violence, deepening inequality, and ideological confusion, his work remains unsettlingly relevant.

He once wrote: “The first step in the struggle for social justice is to understand the nature of the system we are up against.”

For generations of working-class intellectuals, organizers, and scholars across the world, Michael Parenti helped make that understanding possible.

His voice is gone. His clarity remains.

source: Al Mayadeen