This article, the first part of a multi-part series that I will be publishing over the subsequent weeks, provides an overview of Mohammed al-Deif’s (known by his kunya, “Abu Khaled”) most formative operations. It seeks to delineate and illuminate how al-Deif’s leadership shaped the Martyr Izz-al-Din al-Qassam Brigades. Given al-Deif’s enigmatic presence and disciplined operational security, with him having scarcely been photographed or proffered recorded remarks, this requires plumbing the lesser-known resources.

What immediately follows is a transcript documenting the sole interview al-Deif ever participated in, translated into English for the first time. The interview was conducted with Iyad al-Daoud of Al Jazeera, as part of the 2005 program, In the Guesthouse of the Rifle. The film presented an overview of the Izz al-Din al-Qassam Brigades, the military wing of the Islamic Resistance Movement (Hamas), narrated by witness accounts provided by resistance members themselves. On the evening of 9 August 2014, Al Jazeera rebroadcast the film, which had been made shortly after the Zionist occupation’s disengagement from the Gaza Strip in 2005. With strict security precautions in place, the director was blindfolded and guided to an area where al-Qassam members were conducting training operations. In addition to al-Deif, al-Daoud also interviewed the prominent military commander, Aḥmad al-Jabari, who was subsequently martyred in an assassination operation that the occupation undertook on 14 November 2012. He also interviewed numerous anonymous combatants. “It is notable that among them were a number of young fighters who, as the narrator notes, were pursuing their university studies. A group known as “al-murābiṭīn” was also documented as they followed the movements of the occupation army as the latter ambulated along its observation positions.

Mohammed al-Deif, the General Commander of the Brigades of the Martyr ʿIzz al-Dīn al-Qassām: We are a people who have been oppressed, wronged, and expelled from our homes. We seek what is our right. What was it like before 1948? There was no Zionist occupation. This occupation arose by a decision from the United Nations, and the League of Nations turned into the organized gang of the United Nations such that it did not realize our right to these lands. As you have all seen, its [international] laws are only applied to the weak, and thus not applied to the Zionist entity.

We have departments for training, scientific and cultural departments; we also have development and educational departments within the military apparatus. And we are thinking of establishing a military court for the Al-Qassam Brigades so that we can mandate and adhere to a system of formal rules.

[…]

Iyad al-Daoud: 1 January 1992 was the official announcement of the formation of the Qassam Brigades, which came into being after an operation that eliminated the rabbi of the Kfar Darom settlement in Gaza. This beginning was preceded by much preparation.

Ahmed al-Jaabari: We set out to resist the occupiers. Of course, we deployed munitions and organized ourselves, and then we began training. I was arrested and tried, spending 13 years in prison—from early 1982 until early 1995.

Mohammed al-Deif: Our work began in a wing called “the Palestinian Mujahideen.” So began our first military action in 1988, and I was imprisoned in 1989 due to my work with the Palestinian Mujahideen.

[…]

Mohammed al-Deif: There is a supreme military council for the battalions, of course, and there are brigades everywhere. The brigades are made up of several battalions, and the battalions are made up of several companies, and the companies are made up of several platoons, and the platoons are made up of several squads, and the squads are made up of individuals.

Ahmed al-Jabari: Within the military apparatus, we also have special training departments and sectors dedicated to scientific research, development, cultural work, and education. There are also plans to establish a military court for the Martyr Izz al-Din al-Qassam Brigades so that we can continue the founding journey that was started by our mujahideen brothers who preceded us, led by the founding sheikh, Sheikh Salah Shehada, may God have mercy on him.

Mohammed al-Deif: In 1998, we had two cells, and we moved to the West Bank and crated two cells there as well, such that the entire Gaza Strip and the West Bank had four cells in total, two in the Gaza Strip and two in the West Bank. […] By God, I was moving around these lands from the north of the Gaza Strip to the south to the West Bank, working everywhere in this beloved homeland.

Iyad Al-Daoud: And since then, he has been striking everywhere and never revealing himself. They see his actions, but do not know what he looks like.

Mohammed al-Deif: Initially, our work was against [collaborating] agents, then our work became shooting directly at the [occupation] army and conducting bombing operations. Yahya Ayyash was the one who arranged these. The next stage consisted of martyrdom missions until we reached the stage of the tunnel war and stormed the settlements. We ended up eliminating settlers, border guards, army officers, and intelligence. There were many arrangements that we undertook and all aspects of resistance activity were covered, which precipitated the [occupation’s 2005] withdrawal. When our work turned to the “tunnel war,” it marked a qualitative change, as it was the straw that broke the camel’s back.

[…]

Iyad al-Daoud [speaking to Ahmed al-Jabari]: […] Israeli sources say you are the second in charge after Mohammed al-Deif.

Ahmed al-Jabari: Let them say what they want.

Iyad al-Daoud: Sir, this is a place where we love God and his doctrine [of honesty reigns]. What is your official position?

Ahmed al-Jabari: I don’t have a position. I am a mujahid fighting in the way of God Almighty. Wherever there is a field of action in the way of God Almighty, you will find me there, fighting like all the others.

Iyad Al-Daoud: So you do not officially represent Muhammad Al-Deif in the field?

Ahmed Al-Jabari: No, I have the honor of being Mohammed al-Deif’s [de facto] representative in the field, but we do not carry such titles.

Iyad Al-Daoud: Have you carried out operations yourself? And do the soldiers die and receive medals like in the Arab armies?

Ahmed al-Jabari: Of course we are not recipients of medals, nor do we want medals at all. The medal of honor is fighting in the way of Allah. Thanks to Allah, we had the honor of participating, planning, and equipping some of the jihad operations.

Iyad al-Daoud: Sources in the al-Qassam Brigades confirm that they have carried out more than 200 military operations, causing nearly fifty percent of Israeli deaths and injuries in the Gaza Strip since the Al-Aqsa Intifada in 2000.

Ahmed al-Jaabari: I can tell you that ninety percent of the operations carried out by the Qassam Brigades are unique and distinctive because the Qassam Brigades’ operations room will never launch an operation until all matters related to that operation have been planned and completed.

Mohammed Al-Deif: Planning the operation to storm the Gafara Dasmona settlement took us four to five months, as we had to figure out how to get the weapons in. We used a large gas cylinder, which we cut from the bottom, put explosives inside of, and sealed. Of course, one cylinder wasn’t suitable, so we took three cylinders each time. It was important, when entering [the settlement], the cylinder to be opened and the gas released. So my brother went in and opened it, and the gas was released. We rejected operations that had a ten or five percent success rate. For most operations, we found that the success rate was generally more than seventy or eighty percent.

[…]

Anonymous participant [one of the manufacturing department engineers]: Today we are working on an explosive. This place is not a permanent location for preparing the explosive in its third stage. We can move from it and will modify it as necessary. There is an American model that is identical to this explosive. We studied this model and our manufacturing efforts followed the American model. This explosive poses a great danger to the occupation. As an officer in the [Zionist] Defense Forces admitted, that the bomb possessed by the Qassam Brigades can function at a greater distance than the bombs in the possession of the Zionist Defense Forces. This explosive is considered a special weapon for every member of the Al-Qassam Brigades. By the grace of God, large quantities have been distributed to all members of the Al-Qassam Brigades in the Gaza Strip.

Iyad Al-Daoud: How many bombs are manufactured daily?

Anonymous participant: The work is not measured on a daily basis. We have a certain amount that we manufacture monthly, but we cannot disclose it. Of course, the explosive has undergone significant and continuous stages of development. Several leaders of the mujahideen, officials of the Al-Qassam Brigades, and manufacturing researchers participated in this process, including the mujahid commander, may God protect him, Mohammed al-Deif, commander of the Al-Qassam Brigades, and the martyr “Abu Bilal” Al-Ghoul [viz., Adnan al-Ghoul], as well as the martyred mujahid engineer, Yahya Ayyash. There are many other martyrs, including Yasser Taha and Zahir al-Nassar, who worked on developing this bomb, which was initially just an explosive that functioned with a sulfur stick and was ignited manually. It was not mechanical or as advanced as the explosives we use today.

Iyad Al-Daoud: Given that such local manufacturing proves the creativity of Palestinians in adapting the tools of the conflict, what is most important is the human element and the ability to persevere and give. It reminds us that what is more valuable than the weapon is the person who carries it.

Anonymous participant [a perpetrator of the Barakin al-Ghadab Operation]: I entered the tunnel at 5 a.m. after dawn prayers with my brother from the Suqur al-Fatah faction, and we stayed there until just before sunset. We carried out the bombing at 5:30 p.m., then we went to the tower and eliminated seven occupation soldiers. My colleague in the Fatah Falcons was fortunate enough to be martyred in the way of God, and I remained in the battle for a quarter of an hour, then returned to my mujahideen brothers safe and sound, by the grace of God and His guidance.

[…]

Anonymous participant: I am carrying out this martyrdom operation to please God Almighty and to take revenge on the Zionists, to avenge all our martyrs, our children, our women, and our elders, and to avenge Ahmed Yassin and Al-Rantisi.

Iyad Al-Daoud: Have you written your will?

Participant: Yes.

Iyad Al-Daoud: When did you record it?

Participant: About a year ago, shortly after the assassination of Dr. Abdul Aziz Al-Rantisi, may God have mercy on him.

Iyad Al-Daoud: How do you feel now that you have been involved [in resistance activity] for almost a year?

Participant: Death is merely a means to an end, or martyrdom is merely a means to an end, which is to liberate our homeland and lift injustice from humanity.

Mohammed Al-Deif: Life is all about fate. I am married, [and this too] is part of [my] life’s fate. If we want to say that death is simply meaningless, then why would we take security precautions? We move forward and continue, taking into account every security measure, and they [viz., the other resistance fighters who were interviewed] talked a lot about our security precautions in many circumstances. Perhaps you found it difficult to obtain a meeting for this [documentary] because we approach our security very seriously.

[…]

Twelfth participant: The Qassam Brigades are fighting the Zionist tide that kills children, and we, God willing, will eliminate their soldiers, not their children and civilians.

Ahmed al-Jabari: The Jews who came to Palestine were murderers, criminals, rapists, and occupiers. These are the Jews we are fighting. We have no problem with the Jews who live and pray in synagogues in Britain or America. But if they come to Palestine, they are our enemies, and we will fight and eliminate them on Palestinian soil.

Iyad al-Daoud: Is this part of your philosophy—to not take the fight abroad?

Ahmed al-Jabari: Of course, this is the policy of my movement and of the military apparatus.

Mohammed al-Deif: There were no operations against Israeli civilians except in response to the killing of civilians, even though we could have eliminated many. Instead, we undertook targeted operations that were responses. As Sheikh Ahmed Yassin said, ‘Stop killing civilians, and we will stop killing civilians.’

Iyad al-Daoud: Are there clear plans for the West Bank?

Ahmed al-Jaabari: Of course. Speaking about the West Bank without revealing too much, we spare no effort to extend a helping hand to our brothers in the West Bank so that they can achieve liberation, freeing their land just as we liberated Gaza with the help of our mujahideen brothers and their jihad.

Iyad al-Daoud: […] It can be said that the leadership of the Qassam Brigades is seeking by all means to transfer the experience of the Gaza Strip to the West Bank, especially since Al-Deif was a “guest” there and contributed to the establishment of the West Bank resistance apparatus during the early 1990s.

Mohammed al-Deif: The West Bank, the Gaza Strip, and the ‘48 territories are all Palestinian land, which means that we must play a role [in freeing it]—this is our duty and obligation. Not only us as Palestinians, but every Muslim in the world has the right and the obligation to fight for the liberation of this land because it is Islamic land [waqf].

Iyad al-Daoud: Despite the difficult beginnings and less than ideal circumstances, the Qassam Brigades derived their legitimacy from their achievements on the ground. It produced hundreds of leaders from among thousands of martyrs and detainees and managed to become a formidable force in all aspects of the conflict, placing it among the world’s major liberation movements and at the top of the blacklist of those wanted for terrorism.

Ahmed al-Jabari: We are a resistance movement. We are a military organization that takes up arms and will keep those arms, and will keep up this cause. We will continue our strategic goal, which is the complete liberation of Palestine. This jihad is ongoing, and this resistance is continuous. It will neither be stopped by ‘fair justice’ nor unjust oppression. We will continue with our actions and security precautions, God willing, until we complete the journey of liberation.[1]

From the Palestinian Mujahideen to Al-Qassam

During the early 1990s, al-Deif remained constantly on the move, with his on-the-ground work extending across the Gaza Strip and the West Bank. During these years, al-Deif presided over the Qassam Brigades. He oversaw the kidnapping of occupation soldiers and martyrdom operations throughout Palestine, launched explosives toward Tel Aviv, and placed all of the enemy’s cities and settlements within range of the resistance’s missiles. Al-Deif spent 35 years of his life being hunted by the occupation, constituting the longest pursuit in Palestinian history, and, indeed, in the world. During this time, he succeeded in establishing and building an organized military force with which he spearheaded two Intifadas and fought five wars.

Al-Deif inaugurated his resistance career when he joined the ‘Palestinian Mujahideen’ (al-Mujahidun al-Filastiniyyu), which Sheikh Salah Shehadeh founded and supervised as the first military wing of Hamas. The “Palestinian Mujahideen” recruited the most elite and devoted members of the Islamic movement, who constituted the central elite that would lead the military action in its early stages, such as Yasser al-Nimrouti, Jamil Wadi, and Imad ‘Aql.[2] Mohsen Mohammed Saleh, in “The Beginnings of Hamas’s Military Work and the Emergence of the al-Qassam Brigades,” writes that:

After the formation of “the Palestine Apparatus” in late 1985, which took charge of directing action for Palestine at home and abroad, the leadership decided to “invite all its members in all areas of occupied Palestine to participate in demonstrations and clashes with the occupying enemy and even to call for such action.” In light of this, the leadership in GS [viz., Gaza Strip] unanimously agreed in 1986 to start military action. The military apparatus was rebuilt under the name of the “Palestinian Mujahidun [Freedom fighters],” and Ahmad Yasin returned to lead it in mid-June 1987. On 17/11/1987, the military action was launched. Yasin entrusted Salah Shehadeh to form the military apparatus in northern GS, and ‘Abdul ‘Aziz al-Rantisi in southern GS. Due to al-Rantisi’s administrative detention on 15/1/1988, the leadership of this region was entrusted to Salah Shehadeh who thus became the field commander of the military apparatus in GS.[3]

Before the Palestine Apparatus’ formulation in early 1985, the Palestinian Mujahidun’s predecessor framework existed within the auspices of a less defined ‘military committee’ that was tethered to the Palestinian Ikhwan; after the Palestine Apparatus was formed in early 1985, this military committee was absorbed within it. When the Palestinian Mujahidun became independent in 1986, it became independent from the Palestine Apparatus. It should be highlighted that, after it was founded, the Palestinian Mujahidun by no means displaced or overtook the organizational structure of the Palestine Apparatus, which was significantly large an organization and a political body, proper; rather, the Palestinian Mujahidun merely outstripped the facet of the Palestine Apparatus that had been involved in outward-facing military operations within Gaza […] The newly coalesced Palestinian Mujahidun (Al-Mujahidoun Al-Filastinyoun) inaugurated its military actions on 17 December 1987, shortly following the beginning of the First Intifada, with Salah Shehadeh forming the Northern Gaza military cell and ‘Abdul ‘Aziz al-Rantisi directed the southern cell. When al-Rantisi was sentenced with an administrative detention term on 15 January 1988, the southern cell’s leadership coalesced under Salah Shehadeh’s directorship, with the latter subsequently serving as the field commander for the entirety of the Palestinian Mujahidun military apparatus in Gaza.[4]

During this period, the organization tasked Mohammed al-Deif with forming a military group in the southern Gaza Strip. Two years after its establishment and clandestine work, the Palestinian Mujahideen suffered a severe blow when the Zionist occupation uncovered Cell 101, which had been responsible for kidnapping two occupation soldiers. After this, the occupation army launched a widespread campaign of arrests, affecting a large number of the organization’s members, including al-Deif, who was sentenced to two years in prison. During this period, he and Salah Shehadeh were deeply affected by the plight of imprisoned Palestinians. They formed a plan to: as soon as al-Deif was released from prison, he would form a cell dedicated to kidnapping occupation soldiers and exchanging them for the release of imprisoned Palestinians (and Hizbu’llah mujahideen).

A few months after his release, al-Deif resumed fighting, this time under the banner of the Al-Qassam Brigades. He joined the first ranks of the new organization that Yasser al-Nimrouti formed in January 1992, and this organization would lead military work throughout the 1990s. During this period, al-Deif established lines of coordination and communication among the organization’s military structures in Gaza, the West Bank, and Jerusalem. At the end of 1993, al-Deif returned to the Gaza Strip after extremely harsh events unfolded on the ground, including the martyrdom of key members of the Al-Qassam Brigades, the dismantling of numerous military cells, the signing of the Oslo Accords, and the beginning of the return of the Palestinian Authority to the Gaza Strip. These developments marked a new phase in al-Deif’s military career, beginning in 1994, when he assumed the position of military commander of the Al-Qassam Brigades in the Gaza Strip. Within a few months, he rebuilt the organization in a more structured manner and maintained coordination with military groups in the West Bank, a process that culminated in the kidnapping of soldier Nachshon Waxman, an operation that marked al-Deif’s first public appearance announcing the kidnapping at the time. The Waxman operation is considered one of the most important kidnappings in the early history of the Al-Qassam Brigades, as it was the first event coordinated between Al-Qassam’s various cells in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank. Figures ranging from al-Deif and Salah Jadallah from Gaza worked with Yahya Ayyash in the West Bank and Jihad Ya’mur from Jerusalem.[5]

The Zionist entity did not know of al-Deif until the mid-1990s, after the Al-Qassam leadership, headed by al-Deif, made a strategic decision to avenge engineer Yahya Ayyash. In 1996, prisoner Hassan Salama carried out three major operations, and these operations resulted in the deaths of approximately 47 Israelis. Among the violent repercussions was the fall of the Shimon Peres government and the authorities’ implementation of a massive arrest campaign, which led to the liquidation of many organizational and military structures in the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

Al-Deif became the Zionist occupation’s most wanted individual. Yet the security services failed to locate him, despite widespread and massive arrest campaigns that affected most of those who were on the occupation’s wanted list throughout the West Bank and Gaza. The occupation repeatedly tried to pressure him to surrender his weapons and join the security services, which he categorically refused. On one occasion, al-Deif remarked that: “history will record that not everyone surrendered and laid down their arms.”[6] In early 2000, he was arrested by the Preventive Security Service in Gaza City and held for several months before escaping from prison during the Al-Aqsa Intifada with the help of two prison guards.

The Al-Aqsa Intifada was spearheaded by numerous military leaders, some of whom remained outside prison and others who traveled abroad, such as Sheikh Salah Shehadeh, Fawzi Abu al-Qaraʿ, Adnan al-Ghoul, Saad al-Arabid, Muhammad Abu Shamala, and Raed al-Attar.. The most influential figure at that time, al-Deif, oversaw the resistance’s reorganization. Within a few years, they were able to establish an extensive military structure, which became the nucleus of the resistance project. It continued to grow throughout the following years, reaching its peak in the Al-Aqsa Flood.

It is here worth quoting Hassan Kamal’s biography at length, where the author adumbrates several important qualities that al-Deif possessed:

The Al-Qassam Brigades went through significant and complex turning points, some of which had a profound impact on the structure and direction of the brigades, and some of which could have ended their structural and administrative existence, given the extremely difficult security and military situation. This was reflected in the biography of al-Deif, who became the central equation in the history of the Al-Qassam Brigades after 1993. It was represented in three strategic stations that had a major impact on the history of the Palestinian people after the Intifada of Stones [viz., first Intifada], in which al-Deif played a central and sometimes decisive role in the course of events:

The first stage: the signing of the Oslo Accords and its heavy repercussions on the Palestinian people, and the questions it raised at the time, the most important of which were “What should we do? How do we deal with the new reality?” The nationalist and Islamist movements were sharply divided in their responses to this question. The Islamist movement was divided into three positions: the first saw what had happened as a near-total defeat that could not be resisted and thought that it was necessary to see this experiment through to the end. The second position saw the need to confront the Palestinian Authority and the occupation at the same time, considering them as one and the same, and this opinion was very popular among the Islamist base, specifically the fighters among them. The third position clearly distinguished between the Palestinian Authority and the occupation, refusing to consider large sectors that had been fighters and opponents of the occupation a few months earlier to be on the same side

At the same time, he saw the need to continue the jihad and not surrender weapons, a position led by Abu Khaled al-Deif and the groups of the pursued that he leads. During that period, al-Deif focused exclusively on targeting the occupation. He managed to manage relations with figures in the Authority and influence them, as he was keen to forge close ties with many Fatah leaders and security officers, such as Jamal Abu Samhadana, Jihad Abu al-Amareen, Amr Abu Sitta, and others.

The second stage: After the outbreak of the Al-Aqsa Intifada, a huge and intense debate returned within the Islamic movement and the groups of the pursued on how to deal with the new event. A clear trend emerged among them that what was happening was merely a temporary period that Arafat would take advantage of to improve his negotiating position, and that any real involvement in this situation would mean a repeat of the Oslo scenario and the subsequent violent arrests among the pursued. Some of the older members even adopted this view and refused to get involved in the uprising. The second opinion was the exact opposite, arguing that even if the uprising was supported by Arafat, it was necessary to engage fully in it and develop it in such a way that the defeatist current in power could not divert it from its course. Abu Khaled al-Deif adopted this approach, drawing on his experience after his release from prison in 1991 and his ability, within a limited period, to form a military structure capable of broad involvement in the uprising. At the same time, the challenge of organizing and unifying military structures emerged during the first year of the uprising. In 2001, enormous efforts were made, led by al-Deif and Salah Shehadeh, which resulted in the unification of the military structure into a single entity, which was the core of the large military structure of the brigades.

The third stage: the question of resistance and its relationship with the enemy after Israel’s withdrawal from the Gaza Strip. Hamas entered the elections and won by a large margin. There was real and widespread fear among the Islamic movement’s base that Hamas would be “contained” and gradually distanced from its resistance line. This was completely thwarted by Operation “al-Wahm al-Mutabaddid” in 2006, during which Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit was kidnapped. Following this, Israel formulated a policy of tightening the blockade on the Gaza Strip, leading to the Wafa al-Ahrar deal, which resulted in the release of a Palestinian political and military elite, some of whom led the Palestinian resistance in Gaza, such as Yahya Sinwar, while others attempted to revive the armed resistance in the West Bank.

Al-Deif was an exceptional figure in the history of Hamas’ military wing and one of the exceptional leaders in the Palestinian jihad movement, due to his moral and psychological qualities, which were reflected in the structure of the military wing and contributed to transforming a set of personal qualities into established traditions in military work. These psychological traits allowed him to have a profound influence on those he dealt with and enabled him to forge relationships that transcended Islamists and had a profound impact even on his fiercest opponents. Three of his fellow captors during his presentence sentence security services belonged to the al-Qassam Brigades. They were the ones who smuggled him out of prison in Gaza. One of them was Yahya Abu Bakra, a leader of the Al-Qassam Brigades

Al-Deif was loyal to his comrades and to all those who contributed to embracing the resistance. It is said that one of the basic conditions he agreed to in order not to clash with the Preventive Security Force that surrounded him in 2000 was not to harm the people of the house that hosted him. Loyalty, in addition to other values, of course, was a fundamental component informing his decision to avenge the death of Yahya Ayyash, whose assassination could not pass without the occupation-enemy paying a clear price.

The second characteristic relates to patience, perseverance, and forbearance. He decided to return to fighting less than a month after his release in 1991—fthe same decision he made after his release from the Authority’s prisons in 2000. Within a few months, al-Deif began leading large groups of fighters in the Gaza Strip.

The third characteristic, extreme organization, was a trait clearly evident in his ability to lead the largest military force in the history of the Palestinian people, developing and accumulating its strength amid a series of major complications on the ground, particularly during the Al-Aqsa Intifada. This included organizational capabilities that enabled him, within a short period of time, to muster and mobilize thousands of fighters during the early years of the intifada. Nevertheless, al-Deif was not merely a commander-in-chief managing a military force of tens of thousands, but was also a key player and practical supervisor of the force’s development, contributing personally to the military manufacturing project that Adnan al-Ghoul and a group of other leaders inaugurating with him.

His fourth characteristic was extreme modesty, detachment from worldly affairs, and a commitment to Islamic education. This was to be found in most of mujahideen, but it was even more so a quality found in the commanders, as the actions of the commanders have always informed that of the soldiers. This became clear after his martyrdom, particularly after seeing the kind of modest life that his family and children lived under. Their condition was like that of others in their community. His wife and family recounted his insistence on having their children memorize the Qur’an and his great interest in memorization projects in Gaza, especially among the jihadist ranks.

The fifth characteristic is the fading of personal concerns and the dissolution of the individual into the spirit of the group. Despite Abu Khaled’s enormous legitimacy in the history of the Islamic movement, he stayed out of the limelight and there is almost nothing written about him during the first 20 years of his jihadist life. He was keen to avoid getting involved in any internal disputes, no matter how small or large, focusing instead on building an institutional force that belonged to the Palestinian people as a whole. The peak of Palestinian creativity was embodied in the Al-Qassam Brigades, which were formed from strong organizational pillars and structures, strongly linked to the idea of resistance. They trained until they were able to fight and confront the occupation, waging the fiercest Palestinian wars despite the martyrdom of their commander-in-chief in the middle of the battle—in addition to the martyrdom of half of the members of the military council.

The martyr Muhammad al-Deif, “Abu Khaled,” remained a source inspiration, exalted by popular referendum and consensus. His leadership was neither an organizational decision nor a a political pursuit led by some members of the Qassam Brigades. Rather, it emerged spontaneously from the heart of Palestinian society, which chants at every martyr’s funeral, at every demonstration, march, and occasion: “Put the sword against the sword… We are the men of Muhammad al-Deif.”[7]

In the next section, I will provide an account of one of the most important and foundational resistance projects conducted by al-Deif.

The Nachshon Waxman Operation

In October 1994, the Qassam Brigades issued a communique following the kidnapping of a Zionist occupation soldier, Nachshon Waxman, that occurred during that same month. The communique demanded the release of more than 150 prisoners affiliated with the fasāʾil of the Alliance of Palestinian Forces, all of whom were serving long-term prison sentences, in exchange for the release of the soldier. In addition to demanding the release of these prisoners—specifically 50 belonging to Hamas, 25 to Palestinian Islamic Jihad, 50 to Fatah, 20 to the PFLP, 10 to the DFLP, 20 to Hizbu’llah, and 15 to the PFLP-GC—Hamas also demanded the release of Sheikh Yassin and all Palestinian female detainees.[8] The occupation, however, did not release any of these detainees.

Specifically, Prime Minister Rabin stated that he would not yield to the kidnappers’ demands, and he also blamed Yasser Arafat for supposedly providing shelter to the kidnappers in the Gaza Strip. The deadline set by the Qassam Brigades was overtaken by the Zionist occupation’s military attempt to rescue him before the deadline expired. Acting on intelligence reports, the occupation’s military planned and launched a rescue mission intended to extract Waxman from the village of Bir Nabala in the West Bank, but the operation unfolded disastrously. When soldiers stormed the building, Waxman was killed by his three Hamas captors during the assault. In the same exchange of gunfire, the captors also killed another soldier, Captain Nir Poraz.

Five days after the unsuccessful rescue attempt to free Waxman, the Qassam Brigades carried out another attack. On 19 October 1994, a Qassam operative boarded a crowded commuter bus in central Tel Aviv while carrying a bag containing twenty kilograms of explosives, and the device detonated as the bus traveled along the city’s main street. The explosion resulted in the death of twenty-one denizens of the Zionist entity, one Dutch national, and the bomber himself; it also injured fifty other people. Following the bombing, Qassam released a videotaped statement declaring that the attack served as revenge for the deaths of the three Qassam activists who had been killed during the Waxman rescue attempt, and the organization identified the attacker as twenty-seven-year-old Salah Abdel Rahim Suwi.

Suwi appeared in the video and declared that “We will continue our brave suicide operations. There are many young men who long to die for the sake of God.” [9] In response to the failed operation, Rabin ordered another crackdown on the movement. He also declared a complete closure of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip while simultaneously pressuring the Palestinian National Authority (viz., PNA also known as “PA”) to take action against wanted Hamas activists located in the Gaza Strip. The PA responded by arresting hundreds of Hamas leaders and activists, while the occupation military targeted the West Bank with additional operations. Arrest campaigns were organized against Hamas and its supporters throughout October and November, and in both Nablus and Hebron, hundreds of individuals were detained during raids conducted on homes, workplaces, and mosques. Throughout this period, however, al-Deif, who was critical in the Waxman operation, eluded capture.

The following is a narrative description of the Waxman operation, collating the extant sources detailing what transpired.[10]

On 3 October 1994, Hassan Jihad Yaghmour traveled to Nablus to be introduced to the Qassam mujahideen whom he had not yet met. When he arrived, Commander Salah Darwazah introduced him to the three men: Hassan Taysir ʿAbd al-Nabi al-Natsheh from Jerusalem; ʿAbd al-Karim Yasin Badr, a veteran of earlier Qassam capture operations who offered observations and recommendations based on his two prior experiences, allowing the group to draw lessons from those operations; and Salah al-Din Hasan Jadallah, known as Abu Muhammad, from the Gaza Strip. The occupation forces had already placed all three men on wanted lists for military activities. Hassan Jihad Yaghmour took responsibility for transporting the three men to a new house in the Bir Nabala area as the occupation forces did not know him at that time. To strengthen their security precautions, Commander Salah Darwazah secured a large cargo vehicle to transport the three wanted men after their passage through Nablus. Hassan Jihad Yaghmour simultaneously drove ahead in his private car to guide them and to secure their route.

After leaving Nablus, the group drove toward Jerusalem and encountered a military checkpoint that had not previously stood at one of the city’s entrances, which surprised them. Soldiers often stopped cars at the checkpoint and conducted thorough searches. Hassan Jihad Yaghmour drove a car with a yellow license plate, indicating that the car was registered to a citizen of “Israel.”

As soon as the car stopped at the checkpoint and the soldier approached it and noticed that it had a yellow license plate, the mujahid Yaghmour greeted him. The soldier then asked the passengers for their personal documents. Within moments, his eyes fell on a cell phone in the car. He asked Yaghmour to use the phone for a moment, and Yaghmour replied, “You are most welcome.” After the soldier used Jihad’s cell phone, he signaled him to pass without checking the personal documents of the three wanted men, thanking him for giving him the opportunity to talk to his family.

After the mujahideen were able to pass through the checkpoint, they set off for the Bir Nabala area. On the way, the mujahideen began to chat, and the mujahid Hassan al-Natsheh told Jihad Yaghmour that he and Badr had been wanted by the enemy since they carried out a shooting operation against a Zionist cargo truck near Jerusalem. They then used their time to discuss the planning of the capture mission they planned to undertake. Only two steps remained in the preparation phase: firstly, the mujahideen’s safe arrival at the designated safe house so that they could familiarize themselves with it, its entrances and exits, and its weak points. The second step was to switch to the car that would be used in the operation.

In the evening, the mujahideen arrived safely at their new hideout and agreed among themselves that Sunday, 9 October 1994, would be the day of the operation. The group began to make preparations, while Jihad Yaghmour went to rent a car from one of the Zionist car rental companies that would be suitable for this mission. Previous operations had been carried out using either stolen cars, private cars belonging to one of the mujahideen, or cars belonging to the employer of one of the mujahideen. In all three cases, the military groups exposed themselves to danger because the owners of the cars were known to the occupation forces. This time, however, the car that would be used in the operation was rented, shielding the resistance fighters from the occupation’s watch.

On the day of the operation, Yaghmour went to King David Street in Western Jerusalem, where several rental companies operated. Yaghmour entered the first company, called Alon, and tried to rent a private car, but failed after the owner of the company asked for his ID card, which meant that he would have to reveal his real name. Jihad left this company and tried to rent from a second company, but failed again for the same reason. However, he finally managed to rent a car from Shakonir, also located on the same street. The car was a red Volkswagen, and the owner did not ask for his ID card. However, he had to deposit $1,000 as a security deposit for the company. With that, the last obstacle had been overcome. After receiving the rented car, he returned at exactly three o’clock in the afternoon that day to Bir Nabala, where he met the mujahideen with his new red car. There, the three mujahideen had prepared themselves and reviewed the plan. Everyone then dressed in the clothes of religious Zionists and put large black hats on their heads.

Mujahid ʿAbd al-Karim Badr carried an Uzi submachine gun and sat next to the driver, Hassan Jihad Yaghmour. Mujahid Hassan al-Natsheh carried a Galil rifle and sat in the rear seat. Mujahid Salah Jadallah, who carried a pistol, also sat in the back. The two in the back would deceive the soldier into thinking that they were passengers like him. Yaghmour had disguised himself in a shirt with the Zionist occupation’s flag on it. Next to him was Badr, dressed as a rabbi and wearing a kippah. Behind them were the other two, who were dressed as Zionist settlers. Natsheh wore a shirt emblazoned with the Zionist entity’s flag and Jadallah wore clerical garb. This time, their destination was downtown, specifically Ramla (and Ben Yehuda). The mujahideen would travel to the Beit Hanina area, and from there they headed to Ramot junction, near the Ben Gurion Airport. As they drove along, their eyes scanned the sides of the road and monitored the parking places and buses. Hebrew music blared from their radio.

At the side of the road, an occupation soldier stood, looking to hitch a ride. Yaghmour slowed down. Badr remarked to his fellow passengers, “We don’t want him, he’s not carrying a weapon!” Yaghmour nevertheless asked the soldier, “Where are you going?” “To a nearby kibbutz, in this direction,” replied the soldier. “I’m sorry, we’re going in the opposite direction,” said Yaghmour, as the car turned around and headed back down the road.

Yaghmour stopped at the intersection leading to Tel Aviv and took a road to the Yehud Industrial Zone. There, he spotted a Subaru parked on the opposite side of the street. An occupation soldier carrying a weapon and a black military bag got out. Yaghmour accelerated and swerved sharply, causing the passengers’ hats and the Torah scroll placed on the dashboard to tilt. He slowed and honked his horn. The soldier raised his hand and waved, signaling that he was looking for a ride.

Yaghmour stopped the car about twenty meters past the soldier, who ran over, his bag bouncing on his back. “Where are you going?” asked Yaghmour, rolling down the window as Orthodox Pop music played from the car’s speakers. The soldier responded, “To Ramla. Are you going there?” Yaghmour answered “yes” and the soldier opened the door. He sat down next to the two passengers.

The soldier tried to talk to one of them, but the passengers neither turned nor responded to him. Thus, the soldier turned his head towards the side window. The car slowed down after entering a traffic jam on the road leading to the airport, and the radio continued to loudly play music. The soldier, who had just left his station in southern Lebanon, placed his rifle on his lap and closed his eyes. His rifle was unloaded. At that time, the occupation authorities prohibited their soldiers from carrying loaded weapons within the borders of the Palestinian territories occupied in 1948. They were allowed to carry ammunition, but only separately from their weapon.

The soldier, who had drifted asleep, woke up after the car had passed a traffic jam and was heading towards Jerusalem. The car was flanked by woods on both sides of the road. The young man wearing the Zionist entity’s flag on his chest jumped on the soldier, put his arm around his neck, and shouted: “Allahu Akbar!” The soldier grabbed his rifle while attempting to resist al-Natsheh’s grip.

The soldier quickly tried to insert the magazine into his rifle in order to shoot at the mujahideen, but the mujahid ʿAbd al-Karim Badr, who was sitting next to Yaghmour, pulled the magazine from him after jumping from his seat to the back seat where the capture took place. “Kill him, Salah!” shouted al-Natsheh, squeezing the soldier’s neck with all his might, while his colleague joined him in pinning down their prey, who was trying to point the rifle at one of the young men.

Yaghmour shouted, “Don’t kill him, we want him alive!” Badr jumped and grabbed the pistol strapped to Salah Jadallah’s waist. Using all his might, he then struck the soldier’s head with the butt of his pistol. The soldier was subdued. At the same moment, Badr reached with his other hand and pulled the magazine out of the rifle. When Hassan and Jadallah realized that the danger had been neutralized, they covered his mouth with their hands so he couldn’t scream and stuffed a piece of cloth into it.

The three mujahideen managed to tie his hands and feet, cover his head with a piece of cloth, and place a black bag over his head to cover half of his upper body. They then placed him in the rear of the car (behind the seats). The soldier began to scream and threaten. He then asked the mujahideen to leave him alone and not harm him. They reassured him and tried to calm him down several times, telling him that they would not harm him if he remained silent, and that they did not want to kill him.

The soldier’s cries turned into crying and begging: “Don’t kill me! Please don’t kill me!” His mumbles were audible from behind the cloth muzzling his mouth.

“If you don’t want to die, listen to what I have to say,” said Yaghmour, speaking in clear Hebrew. “We are the Al-Qassam Brigades, the military wing of Hamas. We have captured you so that we can release our leader Ahmed Yassin and our brothers from your prisons.” “So you don’t want to kill me?” replied the soldier. His panic soon began to fade. “We want you alive. It’s not in our interest to kill you!” replied Yaghmour. Waxman responded, saying “I promise you I won’t make a sound and I won’t do anything. I haven’t attacked any Palestinians and I haven’t worked against the intifada. I serve in the Golani Brigade in southern Lebanon.”

Everyone understood Hebrew except Jadallah, who was from Gaza, so he asked them, “What is he saying?” Badr said, “He wants to wash his hands of our blood, as if the Lebanese are not one of us!” Hassan then asked him, “Where are you from?” “From Jerusalem,” replied the soldier. The young men burst out laughing, “Oh… he’s from our hometown!”

To reassure the soldier, Yaghmour spoke to him in Hebrew throughout the journey. He learned that the captured soldier’s name was Nahshon Waxman and that he lived with his mother in the Ramot area near Jerusalem. He also learned that he had served in southern Lebanon for three months and was planning to travel to Ramla, where his friend lived.

The soldier looked at them with questioning eyes, and the driver said: “Thank God, we made it through the Erez crossing!” The soldier burst into tears: “Please don’t take me to Gaza, don’t take me to Gaza! I beg you… I don’t want to go to hell.”

After a short period of time, the mujahideen arrived at the Jerusalem Road, and from there they drove to the Beit Shemesh junction. They then turned towards the Givat Ze’ev settlement. From there, they continued traveling until they finally reached the Bir Nabala area, where the house they had prepared to hide the captured soldier was located. By then, it was almost 7:30 p.m. After making sure the location was safe and securing the area thoroughly, the mujahideen took Waxman out of the car and brought him into the house, placing him in the bedroom (which was the most secure and fortified room). He remained there until the early hours of the morning. The third phase of the operation was then initiated.

The third phase began when Yaghmour went to a photography shop in the Beit Hanina area to rent a video camera. He then returned to the house where the captured soldier and the three mujahideen were staying. Upon his arrival, Yaghmour spoke calmly to the captured soldier, reassuring him once again that no one would harm him as long as he remained calm and did not try to resist or escape. He then asked him to prepare to deliver a message in front of the camera, in which he was to reassure his family that he was alive and well. In the message, he would demand that his government’s prime minister, Yitzhak Rabin, meet the mujahideen’s demands.

Whenever the resistance fighters wanted to remove their masks, they would put the soldier’s mask on their faces and vice versa, so that the soldier would not recognize their features and they would not be pursued by the Zionist intelligence services if the deal went through and the soldier returned to his family. Badr took the video, while the mujahid Salah Jadallah stood behind the soldier, his face wrapped with a keffiyeh, holding the soldier’s weapon and ID card; he read the military statement of the Qassam Brigades, written in Yaghmour’s handwriting. The statement read as follows:

{Fight them, and Allah will punish them by your hands and disgrace them and give you victory over them and heal the breasts of a believing people.}

Military statement issued by:

Al-Qassam Brigades

The Martyr ʿIzz al-Din al-Qassam Brigades claim responsibility for the capture of the Zionist soldier named Nahshon Mordechai Waxman, ID number 03228629, who is now in our custody alive and provided sustenance and is being treated as a prisoner in accordance with Islamic law. In light of this, we demand the following from the Zionist government:

First: The immediate and swift release of the leader of the Islamic Resistance Movement, Hamas, Sheikh Ahmad Yasin, Sheikh Salah Shahada, Sheikh ʿAbd al-Karim ʿUbayd, and Sheikh Mustafa al-Dirani.

Second: The release of all prisoners belonging to the Martyr ʿIzz al-Din al-Qassam Brigades.

Third: The release of 50 persons from the Hamas movement from among those with high sentences.

50 persons from the Islamic Jihad movement from among those with high sentences.

50 persons from the Palestinian National Liberation Movement Fatah from among those with high sentences.

20 persons from the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (George Habash).

10 persons from the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine.

20 persons from Hezbollah.

5 persons from the Popular Front – General Command.

The next day, the cell sent the tape recording of Waxman, along with his military papers, to the mastermind of the operation in Gaza. The man behind the operation, who had remained unknown to them, had recruited them with great perspicacity, selecting them from different areas so that they would not be detected or associated with one another by the occupation. Thus, some were selected from Jerusalem, Hebron and other areas in the West Bank, and Gaza.

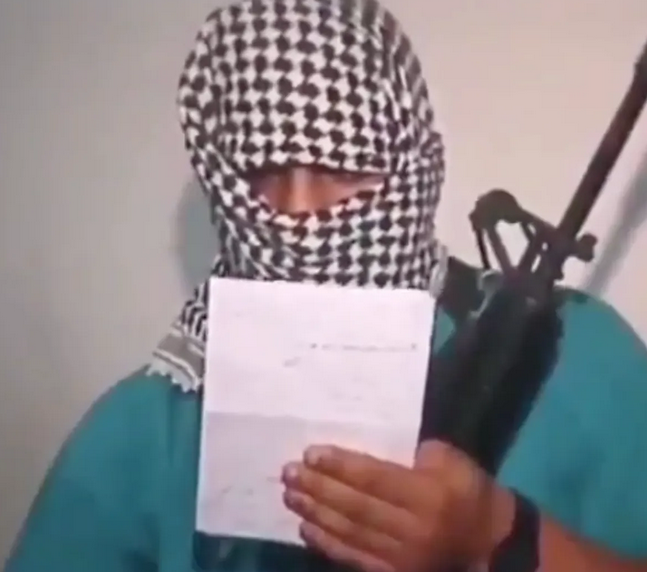

Upon receiving the tape, a man appeared who wore a Palestinian keffiyeh and a green shirt. Holding a piece of paper, he read a supplemental recorded statement about the operation to be distributed to the Zionist press:

The Al-Qassam Brigades claim responsibility for the capture of Israeli soldier Nahshon Mordechai [Waxman], and we demand the immediate and swift release of the leader of the Islamic Resistance Movement, Hamas, Sheikh Ahmed Yassin …

The masked man warned the occupation government that any attempt to manipulate or circumvent the demands would lead to the prisoner’s execution.

When Hebrew media broadcast the clip, the Zionist entity saw, for the first time in its history, Muhammad bin Diab bin Ibrahim al-Masri, better known as “al-Deif.” He presented a list of prisoners whom the occupation authorities were required to release in exchange for Waxman, including 50 prisoners from Hamas, 25 from the Palestinian Islamic Jihad Movement, 50 prisoners from Fatah with long sentences, 20 prisoners from the Popular Front, 10 from the Democratic Front, 20 from Hizbu’llah, and all Palestinian female prisoners.

To be continued.

[1] “Hosted by Venice… Al-Qassam Brigades,” Al Jzeera, 10 August 2014; retrieved online (30 January 2026): https://shorturl.at/bR90m

[2] The Qassam Brigades’ own publications, including al-Nimrouti’s biography, refer to him as the first commander of Qassam; see the official Qassam magazine “Al-Mيدان,” issue No. 3.

[3] Mohsen Mohammed Saleh, “Political Analysis: The Beginnings of Hamas’s Military Action and the Emergence of al-Qassam Brigades” (English version), retrieved online (21 September 2025): https://tinyurl.com/4tffmk4j

[4] “The History Behind Hamas’s Intelligence Apparatus and Understanding its Approach to the Abu Shabab Gang and Other Collaborator Networks: On Al-Majd, Al-Mujahidun Al-Filastiniyyun, and Al-Qiwa Al-Tanfîdîyâ,” Substack, 27 September 2025; retrieved online (25 January 2026): https://mujammaharaket.substack.com/p/the-history-behind-hamass-intelligence

[5] Ghassan Du‘ar, Imad ‘Aql, Legend of Jihad and Resistance (London: Filastin al-Muslimah, 1994).

[6] Hassan Kamal, “Biography of the venerable shadow: Muhammed al-Deif,” Metras, 13 February 2025; retrieved online (25 January 2026): https://shorturl.at/HeOey .

[7] Ibid.

[8] Military communique of the Martyr ‘Izzidin al-Qassam Brigades, 11 October 1994; also see Khaled Hroub, Hamas: Political Thought and Practice (Beirut: Institute for Palestine Studies, 2000), p. 123.

[9] Palestine Report, 23 October 1994, p. 1.

[10] What follows is a reconstruction based on the following sources: Ghassan Du‘ar’s Harb al-Ayyam al-Sab‘ah: ’Usud Hamas (Amman: Filastin al-Muslima, 1993); Ghassan Du‘ar, Imad ‘Aql, Legend of Jihad and Resistance (London, Filastin al-Muslimah, 1994); See United Nations General Assembly, Report of the Special Committee to Investigate Israeli Practices Affecting the Human Rights of the Palestinian People and Other Arabs of the Occupied Territories, 24 March 1995; retrieved online (8 February 2026): https://unispal.un.org/pdfs/D4AB68AAA63D90FC85256219005770C9.pdf ; Hassan Salama, The Buses Are Burning (2022); Abeed al-Qudus al-Hashimi, “The Story of the Cunning Man: Mohammed al-Deif,” Metras, op. cit.

source: Mujamma Haraket