The current geopolitical landscape of Our America is marked by an aggressive escalation by US imperialism, who have cast aside any pretense of multilateralism or respect for international law. The vile military attack on Venezuela, the arbitrary and illegal kidnapping of its constitutional President Nicolás Maduro, the cowardly murder of more than 100 Venezuelans and Cubans, the explicit military threats against Colombia, Mexico, and, especially, Cuba, and the intensification of suffocating economic blockades are not isolated incidents. These events are links in the same chain of domination, designed to reverse any project of national sovereignty or independent regional integration. Faced with this multidimensional offensive, which combines economic war, psychological operations, cybernetic actions, and the use or threat of the direct use of force, the response of the people cannot be limited to the diplomatic sphere or to occasional defensive reactions.

Education to forge conscious and practical rejection

The education of the people for a conscious and practical rejection becomes imperative, as a condition of survival itself. Conscious, because it must be rooted in a profound understanding of the historical, economic, and cultural mechanisms of imperialism. Practical, because it must translate into organized mobilization, defense of legitimate institutions, active internationalist solidarity, and the daily construction of alternatives. Education, in its broadest and most transformative sense, is the fundamental tool for forging this capacity for response. Far from being a cultural appendage, it is the primary battlefield where the battle of ideas is won or lost, a battle that precedes and conditions every other form of confrontation.

From alphabetization to critical literacy

Education is not neutral; the literacy of the people is the primordial foundation. No one who experienced the 1961 Literacy Campaign in Cuba, in which I had the opportunity to participate as a child, can harbor any illusions about the neutrality of education. That episode, where more than 100,000 of us young people marched to the fields and mountains to teach reading and writing, was an act of profound subversion of the neocolonial order. We literacy teachers did not carry only primers and manuals; we carried a revolutionary idea: that knowledge is a universal right and an instrument of liberation. The murders of young literacy teachers Conrado Benítez and Manuel Ascunce Domenech at the hands of counter-revolutionary bands armed and financed by the CIA demonstrated with brutality that the oligarchy and imperialism understood perfectly the danger posed by an enlightened people.

Today, illiteracy in the world has mutated. Alongside residual illiteracy, a functional, political, and digital illiteracy persists, carefully cultivated by a transnational media ecosystem in the service of capital. It consists of the inability to decode the interests behind a news story, to contextualize a geopolitical conflict, to recognize what the doctrines of “hybrid warfare” or “soft coups” represent. People, bombarded by narratives that present victims as perpetrators and aggressors as saviors, can be driven to act (even electorally) against their own class and national interests. Disinformation about Venezuela or about Cuba, where the grave consequences of an economic war and a sustained genocidal economic, commercial, and financial blockade are presented as the “failure of socialism,” is the weapon of choice for these protagonists in such a cruel phenomenon.

Therefore, contemporary education must have as its backbone the general education of the people and critical media and historical literacy. It must teach how to dismantle propaganda, identify primary sources, trace the ownership of media outlets, and understand the history of cruel colonial exploitation, of Yankee interventions in the region, from Mexico in 1847 to Panama in 1989, and now the aggression against Venezuela in 2026. Only a people capable of “reading between the lines” or interpreting the hegemonic discourse (which is increasingly crude) can generate the conscious rejection necessary in the face of intoxication campaigns that seek to demoralize, divide, and paralyze resistance.

Cognitive war: The disinformation campaign against Venezuela

A paradigmatic example of this phenomenon is the intense disinformation campaign deployed following the military aggression against Venezuela on January 3rd and the illegal kidnapping of President Nicolás Maduro, with a clear political objective: to erode the legitimacy and unity of the Bolivarian government. This operation seeks to present Chavismo as a defeated movement betrayed from within, falsely claiming that key figures like Delcy Rodríguez or Diosdado Cabello made a pact with Washington to overthrow Maduro. These narratives, amplified by hegemonic media aligned with the interests of the White House, are based mainly on fabricated sources and have been categorically denied by the Venezuelan government. Their purpose is to sow confusion and demoralization, attempting to fracture popular support and weaken resistance in the face of what is, in essence, an act of war and a flagrant violation of international law.

The architecture of this manipulation is multifaceted. On one hand, strategic falsehoods are disseminated about a supposed economic and political surrender of Venezuela promoted by President Donald Trump himself, seeking to fabricate a narrative of submission and benefit. On the other, false audiovisual content designed to provoke an immediate emotional impact is viralized: videos of popular celebrations in Caracas that were actually filmed in Santiago de Chile, images generated by artificial intelligence of Maduro in prison, or movie scenes presented as evidence of real torture of opponents. Even a video of the bombing of the Bolivarian Militia Command was manipulated to pass it off as an attack on the mausoleum of Hugo Chávez, a cynical attempt to wound the foundational symbol of Chavismo. These fake news items are not casual errors, but components of a cognitive war that seeks to rewrite the perception of reality, making resistance seem useless and collaboration a fait accompli.

The ultimate goal of this campaign is threefold: first, to deny the imperialist nature of the military operation, presenting it as a “clean” intervention or even one desired internally. Second, to project an image of absolute control by Washington, under which any action by the interim Venezuelan government is interpreted as subordination to Trump, ignoring firm statements of condemnation and constitutional continuity. And third, to isolate Venezuela internationally, making its government appear illegitimate and divided, despite the widespread rejection of the aggression expressed by countries like Mexico, Colombia, and Cuba, which have called it a dangerous precedent against sovereignty and the UN Charter. These narratives constitute yet another assault on the country’s sovereignty, waged on the battlefield of information, where the annihilation of truth is the fundamental objective.

From Gramsci’s hegemony to decolonizing thought

The construction of a proper and decolonizing thought in Our America and the Third World provides the theoretical arsenal to confront such distortions. Marxism, by denouncing that the ideas of the ruling class are the ruling ideas in every epoch, laid the foundations for understanding schools and the media as ideological apparatuses. The thought of Antonio Gramsci enriched this analysis with his concept of hegemony, explaining how the ruling class maintains itself not only through state coercion but through cultural consensus, achieving that its worldview is accepted as “common sense” by the broad masses. The battle for this hegemony is a “war of position” waged precisely in the trenches of civil society: in schools, in the media, in culture.

It was precisely thinkers from the periphery who deepened the cultural and colonial dimension of domination. José Martí, the Apostle of Cuban Independence, with his vision that “to be cultured is the only way to be free” established the indissoluble link between national independence and sovereignty of thought. For Martí, education should form people “for life,” not to serve foreign interests. Paulo Freire, from the pedagogy of the oppressed, transformed education into an act of dialogue and conscientization, where “reading the word” is inseparable from “reading the world” to transform it. His method rejects “banking education,” which deposits passive information, and promotes a problem-posing education that makes every student a critical subject.

From Algeria, Frantz Fanon exposed how colonialism occupies not only territories but also minds, imposing cultural inferiorization and a rupture with one’s own history. Decolonization, to be real, must include a “decolonization of the mind,” a rescue of one’s own culture and history as sources of identity and resistance. The Syrian Constantine Zurayk argued, after the Palestinian Nakba, that true independence is impossible without an “education of national dignity” that combats the mentality of defeat and dependence.

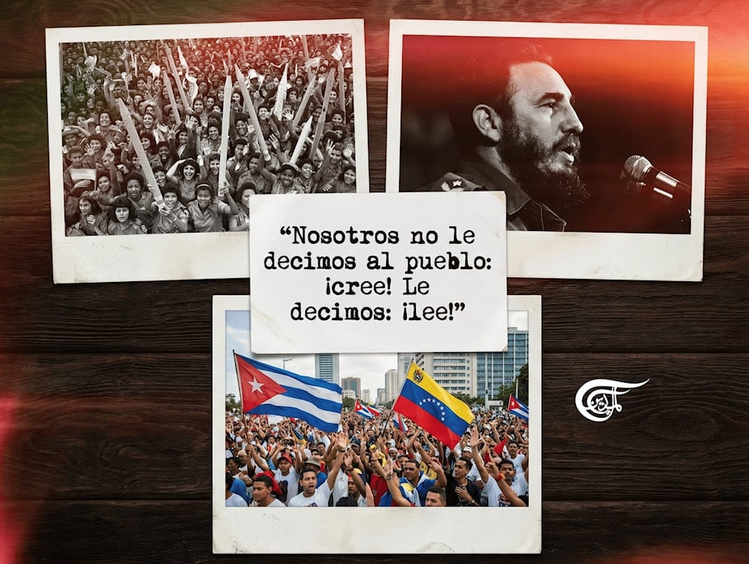

In Cuba, Fidel Castro synthesized and put these ideas into massive practice. His long, didactic speeches were lessons in history, political economy, and internationalist ethics. His maxim, “Don’t believe, read!” is the core of a revolutionary ethic of knowledge: it is a call to methodical doubt, to one’s own investigation, to not delegate to others the interpretation of reality. Fidel went further, vehemently defending a comprehensive general culture, a formation that unites sciences and humanities, theory and practice, breaking the capitalist division between manual and intellectual labor. A people fragmented in their knowledge is a people vulnerable to manipulation. A people with an integral culture can understand the complexity of the world and, therefore, properly appreciate what surrounds them and defend themselves better.

Sovereignty vs. subordination

The 20th century offered two antagonistic models. On one hand, socialist experiences and national liberation movements prioritized mass education and the eradication of illiteracy as pillars of national construction and sovereignty. In the USSR, China, Vietnam, and Cuba, education was an engine of social mobility and the creation of endogenous scientific capabilities. On the other hand, capitalist educational “miracles” in Asia (South Korea, Singapore…) certainly achieved high technical performance but at an enormous human cost: systems of fierce competitiveness, student alienation, and an education functionalized exclusively for the labor market, without critical spirit and social purposes. However, even within capitalist frameworks, some leaders attempted to imprint a sovereign character on education. Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad promoted an education with strong nationalist and anti-imperialist content, seeking to create a local industrial bourgeoisie and reduce mental dependence. In Tanzania, Julius Nyerere pushed for “Education for Self-Reliance,” linking school to community production and African values of ujamaa (extended family), although it was later strangled by IMF conditionalities.

These contrasting examples reveal a crucial truth: an educational system that is not in the service of a sovereign national project ends up, inevitably, serving a project of subordination to global centers of power. Technically efficient but uncritical education produces excellent employees for transnational corporations, but passive and submissive citizens in the face of class exploitation and the plunder of their homeland’s resources. The education we need today must form technicians and patriots, scientists and internationalists, professionals and defenders of sovereignty.

Cuba’s educational sovereignty under siege

The case of Cuba is paradigmatic. From being a country with one of the highest illiteracy rates in Latin America in 1959, it was transformed, in a few decades, into an educational and scientific power recognized worldwide. This leap was not the result of a technical recipe, but of a clear political will that has prioritized the human being as the center of development. The Literacy Campaign was the foundational act, but the system expanded universally and completely free of charge, from infant daycare to postgraduate studies. The divorce between the lettered city and the countryside, between science and the people, was broken. The formation of patriotic and solidary Cubans and of tens of thousands of doctors, engineers, teachers, and scientists became the material basis for achieving milestones like the biotechnology industry, capable of creating its own vaccines (like the anti-COVID Abdala and Soberana) amid a tightened blockade.

The most eloquent fact: during the Special Period, in the midst of the deepest economic crisis, Cuba did not close a single school. Today, it allocates around 13% of its GDP to education. This is not a mere statistic; it is a declaration of principles in a world where knowledge is commodified. It demonstrates that, even under the fiercest siege, it is possible and necessary to defend education as a bastion of national sovereignty. An educated people is a people that can resist, innovate, and sustain itself when the doors of international commerce tend to close due to foreign coercion.

The patriotic Cuban people endured the Special Period stoically without surrendering, despite the relentless US blockade. In the current menacing juncture, although Cubans love and enjoy peace, we are willing and prepared to face any circumstance with the objective of defending our independence and sovereignty. Any attempt of aggression against our country by Yankee imperialism would cause great hardship, but would carry an immense cost for the US and would fail due to the active and steadfast resistance of the overwhelming majority of the people. Such an aggression would represent an inescapable trap for the empire.

Cuban educational internationalism extends the principle that education is the primary means of shaping individuals capable of understanding reality and resisting injustice. UNESCO-endorsed, the simple yet profound “Yes, I Can” literacy method has taught over 10 million people across more than 30 countries to read and write. As ambassador in Australia, I witnessed its transformative impact in segregated Aboriginal communities, like the case of Wilcannia. There, adults who learned to read and write not only signed their name for the first time; they began using computers, understanding official documents, and communicating with distant relatives. The incidence of social problems decreased. The recovered word was synonymous with recovered dignity and strengthened organizational capacity.

Cognitive capitalism and the trenches of resistance

Imperialism has modernized its tools of intellectual domination. Today, we face cognitive capitalism, a phase where the main source of value and control is the extraction of data, attention, and knowledge itself. Large digital platforms (Google, Meta, etc.), with their offer of “free education” and access to information, act as new mechanisms of colonization, homogenizing thought, imposing English as a lingua franca, and turning users into products whose data is sold. The financialization of higher education, with student debts that enslave entire generations (like the 1.7 trillion dollars in the USA), is an effective mechanism of social discipline: those who are in debt become cautious, less prone to challenge the system. The algorithm threatens to replace the teacher, promising personalization but imposing hidden standards and a fragmented vision of knowledge.

Faced with this panorama, educational resistance tends to reorganize into new trenches: Indigenous universities in Latin America challenge academic Eurocentrism, validating their own epistemologies; the Landless Rural Workers Movement (MST) in Brazil creates schools where agroecology and class consciousness are taught; in Europe and the USA, collectively managed schools grow, and young people in Africa and Asia develop educational platforms in local languages. These diverse but convergent experiences prove that another education is possible: one that arises from the concrete needs and interests of the people, that strengthens identities, that is managed democratically, and that has as its end emancipation, not adaptation to the market.

Ideological immunity and sovereignty

The education we need for these times of aggression cannot be just another curriculum. It must be an explicit political-pedagogical project for the integral defense of sovereignty. It must substantively integrate indigenous, Afro-descendant, and popular knowledges; explain what imperialism is and analyze concrete cases like Venezuela; foster strategic thinking and unity, and show that aggression against a brother country is an attack on the entire Great Homeland; train in sciences with awareness of national development, and teach how to create community media and one’s own communication networks.

Fidel’s maxim, “Don’t believe, read!” and Martí’s, “To be cultured is the only way to be free,” are not decorative slogans: they are essences for survival in the unconventional war we are living. A critically educated people is a people with ideological immunity. It is a people that does not swallow whole the narrative of the “regime” fabricated in Washington. It is a people that can organize practical rejection. Cuba, with its achievements and its limitations, is not a model to be copied mechanically, but a hopeful testimony: even under the most adverse conditions, the commitment to the formation and quality education for all builds a wall of dignity that not even the most powerful empire has been able to tear down. Today’s task is to universalize that principle, so that every child, every young person, every worker in Our America not only learns to read and write, but to read the world with their own eyes, to write their history with their own hands, and to defend their future with an unbreakable consciousness. In that education lays the seed of the definitive defeat of the imperial project.

Faced with the multidimensional war unleashed by imperialism, which finds its most brutal and criminal expression in the aggression against Venezuela, education stands not as a refuge, but as the workshop where the antidote is forged: a conscious people. A people that, by learning to read the world with their own eyes, disarms the lies that justify plunder; that, by writing their history with their own hands, raises the barricades of national dignity. The future of Our America, its capacity to resist, re-exist, and overcome, is decided in this battle for consciousness. And it is in the unwavering defense of Venezuelan sovereignty that today, with total clarity, the decisive combat for that future is being waged.

Bibliographic references

- Castro, F. (1961). Palabras a los intelectuales [Discurso]. Departamento de Versiones Taquigráficas del Gobierno Revolucionario.

- Chomsky, N., & Herman, E. S. (1988). Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media. Pantheon Books.

- Constitución de la República Bolivariana de Venezuela. (1999).

- Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogía del Oprimido. Siglo XXI Editores.

- Golinger, E. (2005). El código Chávez: Descifrando la intervención de EE.UU. en Venezuela. Editorial Sur.

- Gramsci, A. (1971). Selections from the Prison Notebooks (Q. Hoare & G. N. Smith, Eds. & Trans.). International Publishers.

- Maduro, N. (2026, enero 4). Declaración ante el ataque imperial a la Patria [Comunicado oficial]. Presidencia de la República Bolivariana de Venezuela.

- Martí, J. (1891). Nuestra América. En La Revista Ilustrada de Nueva York.

- Ministerio del Poder Popular para la Comunicación y la Información de Venezuela. (2026, enero). Dossier: Pruebas de la operación militar ilegal y la campaña de desinformación.

- Rodríguez, S. (1840). Sociedades Americanas. Imprenta de J. R. Navarro.

Pedro Barata

Source: Al Mayadeen