Before dusk on 26 November, fighters from Hamas’ military wing, Al-Qassam Brigades, began the process of handing over to the International Red Cross a number of Israeli captives taken during the 7 October Al-Aqsa Flood operation. The transfer of these women and children took place in the Gaza Strip amid what appeared to be a security parade. Al-Qassam fighters arrived in four-wheel-drive vehicles and deployed themselves around the site, wearing full uniforms and bearing arms. Surrounded by civilians cheering on the resistance, the transfer of the Israeli captives was completed smoothly and quietly.

This event took place in Palestine Square in Gaza City on the third day of the truce that followed a 49-day war. Throughout the war, Gaza City has been subjected to a suffocating siege and an unprecedented Israeli air and artillery assault, not seen since at least 1982.

The handover process in Palestine Square also took place more than a month after the Israeli army began its ground operation, in which it aims to occupy Gaza City and all areas north of the Strip, destroy them, and displace their population permanently. But the visual of Al-Qassam fighters confidently standing guard in Palestine Square on 26 November, suggested to all present that they remained unharmed by Israel’s war.

The fighters transported the Israeli prisoners from their various hideouts and agreed-upon pickup sites to the square, while ensuring that these safe houses would not be discovered. Somebody issued the order, and others carried it out seamlessly, in a highly visible geographical area of less than 150 square kilometers. Keep in mind that Israel and the US have allocated enormous intelligence resources over the past six weeks to unearth the vast network of Hamas tunnels, and to discover the whereabouts of the prisoners.

This picture reveals, to a large extent, the results of Israel’s ground operation: civilian massacres and infrastructural destruction galore, but with little damage to the military structure of the Palestinian resistance. A number of its leaders have indeed been killed – most recently Al-Qassam’s northern commander and military council member Ahmed al-Ghandour – but its command and control system still ticks on effectively.

Israel’s ground limits

Further evidence of this lies in the inability of the occupation army to penetrate, unimpeded, all of northern Gaza. Israel precedes its ground movements with intense air strikes, then artillery shelling. After destroying everything in its path, its tanks begin advancing. It is almost impossible to confront tanks as they enter, because air fire clears spaces 500 meters ahead, while artillery shells pave the path 150 meters in front of the ground units.

However, whenever possible, the resistance fighters launch anti-armor missiles – Cornet, Conkurs, or similar types – with ranges exceeding one thousand metres. After the tanks reach their designated target, the resistance fighters emerge like ghosts from under the ground or rubble and fire anti-armor shells at them, usually Al-Yassin homemade shells, with a range of fewer than 150 meters. Or, alternatively, a fighter physically approaches the Israeli tanks and plants a sticky bomb that explodes in much the same way as a hand grenade.

The work of resistance does not end there. If the tanks do not retreat, and the occupation soldiers settle in, they will be attacked with machine gun fire or explosive devices. The Palestinian fighters film many of these operations, and the footage is delivered to the operations room, which decides what to publish.

It is clear that the resistance’s command and control system is still operating effectively.

Bigger than the 1973 war?

The Israeli ground operation in the northern Gaza Strip began after three weeks of preliminary air attacks and preparation by the invasion forces.

More than 100,000 soldiers were mobilized around the Gaza Strip, which has a total area of about 360 square kilometers.

Most of these troops belong to the regular forces, and Israel called up a further 300,000 reserve soldiers and officers – more than the number of reservists called up by Russia to fight on a 1,500 km front. In northern Gaza, Israel has thus far deployed its regular (non-reserve) combat brigades and battalions: Golani Brigade, Nahal Brigade, Givati Brigade, Paratroopers, Special Operations Force “Shayetet 13,” Special Staff Operations Unit (Sayeret Matkal), and so forth. All the regular forces that the occupation army could muster have been fully deployed in the Gaza Strip since the start of the fourth week of the war.

In addition, Israel has mobilized half of its artillery stock, half of its air force, and one thousand armored vehicles, including tanks and troop carriers.

Estimates of the Palestinian resistance suggest that the total number of regular and reserve forces deployed on the borders of the Gaza Strip, and inside it, exceeds the number of Israeli troops that participated in the 1973 war counterattacks on the Syrian and Egyptian fronts.

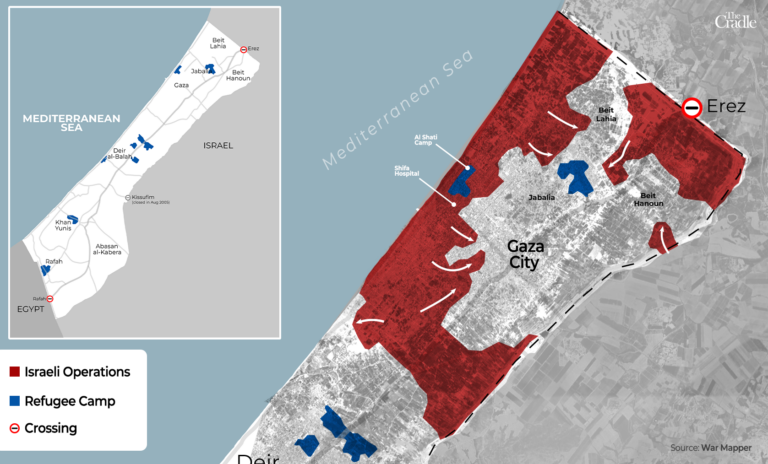

In this war, the Israelis have not attempted to penetrate Gaza from the “traditional axes,” that is, from the east toward the Shuja’iya neighborhood in Gaza City. Their incursion, instead, commenced in the center of the Strip, in the area called “Wadi Gaza” with low population and urban density, which means that the resistance’s ability to confront it is also low.

The occupation army was able to enter this area, from east to west, effectively severing the north of the Strip from its south. However, until the truce took effect, resistance fighters were still carrying out operations against Israeli troops, particularly in the Juhr al-Dik area.

The other axis of the incursion was in the Beit Lahia and Beit Hanoun areas of northern Gaza. As of 24 November, when a temporary truce was announced, the occupation army had been unable to control the region and continued to face deadly operations carried out by various resistance troops.

The third and main axis of advance is in western Gaza, along the shoreline of the northern Strip. Israeli tanks advanced from the north and from the centre, along the Mediterranean coast, to penetrate all the way to Al-Shifa Hospital and other government centers, such as the Legislative Council building.

Gaza Beach…the resistance’s weak point

Along the coastline, there are no defensive resistance tunnels, due to the nature of the land, the lack of population and infrastructure, and the possibility of seawater leaking into the tunnels. The most that the resistance could have achieved, defensively, in this axis, was to repel naval landings – not to stop the advance of tanks or the devastating airstrikes that precede them.

The main node in this axis is the Beach camp, which the occupation army has been unable to enter because of the ferocity of the resistance there.

So far, Tel Aviv has acknowledged the death of over 70 soldiers and officers, with hundreds of others wounded. Palestinian resistance sources confirm that the actual confrontation with Israeli troops only began after they entered the Shifa Medical Complex.

The frequency and intensity of Israel’s aerial and artillery bombardments do not allow resistance fighters to repel the occupation’s advancement, as the overwhelming firepower detonates most of the IEDs intended for tanks or infantry and blocks or destroys entrances to tunnels.

For this reason, the resistance waits for a lull in the bombing, the entry of tanks, and the reopening of the tunnels to begin its operations. At this stage, the fighters wait for Israeli infantry to emerge from their armored vehicles in order to target them. This has already occurred in a number of operations in the northern and western axes of occupation troops movements.

So far, the resistance confirms that it has damaged and destroyed more than 300 Israeli armored vehicles. Some of them were removed from service, while others are maintained in the field for reuse. The sources further confirm to The Cradle that the number of Israeli troop casualties, both dead and wounded, is many times greater than what Tel Aviv has announced.

Now, where to?

Before the 24 November truce, the occupation army had exhausted its ability to maneuver on the ground, having already deployed the majority of its regular combat forces in the northern and western axes.

It will need to search for innovative solutions if it seeks to advance toward densely populated areas in northern Gaza, such as Jabalia refugee camp, the Al-Zaytoun and Al-Shuja’iya neighborhoods, Al-Shati beach camp, and other vital places the Israelis have failed to penetrate. These areas are the ground zero of the Palestinian resistance, in which these forces have prepared themselves – and their tunnel infrastructure – for fierce and protracted confrontations.

The main reason the occupation government agreed to a short truce is that its ground incursion had hit this wall – in addition to other factors such as US pressure to release American captives. Simply put, the Israeli army needs to re-examine its plans and develop new strategies to advance in the field.

It is important to note that norms applicable in regular armed conflicts, as in Ukraine, Syria, Iraq, or Sudan, do not necessarily apply to the Gaza Strip. When a control map shows the Ukrainian army controlling a region, the Russian army has withdrawn from it, and vice versa.

In Gaza, a map showing the Israeli army in an area does not necessarily mean a withdrawal of Palestinian resistance forces, as the latter do not have armored vehicles or traditional formations to remove from enemy-invaded areas. Its fighters simply disappear underground to await the emergence of occupation soldiers from their tanks and such.

The bottom line is that maps currently circulated by governments, media, and think tanks that display Israel’s field advancement in Gaza – accurate or not – are not illustrating Israel’s ground control, but rather the depth of its incursions.

At the truce’s end, even if extended further, Tel Aviv will relaunch its ground operation. It will first prep the field with even more ferocious air bombardment than before, intended to displace more than 700,000 civilians remaining in the northern Gaza Strip and to impact the morale of resistance fighters.

It is also expected that the latter has studied the ground reality well, modified its defensive plans, carefully determined its goals, and reorganized its defense lines to fight the enemy with greater efficacy and inflict the greatest possible losses upon it.

Israel’s goal is to crush the resistance in northern Gaza in preparation for its next-phase war on the south – which may be fought differently, both strategically and tactically. What the resistance wants is to force the enemy to stop the war.

Hasan Illaik

https://new.thecradle.co/articles/israels-ground-war-conundrum