Kissinger’s death finally allows us to expose and dissect the ideological and cultural cornerstones on which much of American foreign policy is built. Since the 1960s, the Kissinger approach towards the so-called Third World has set the diplomatic standard for the US to integrate Orientalism in International Relations.

As the Palestinian intellectual Edward Said explained, “both traditional orientalists and Kissinger conceive the difference between cultures, firstly, as a kind of front line along which they oppose each other, and secondly as an exhortation to the West so that it controls, contains and governs the Other, in the name of its superiority in every field, first and foremost that of knowledge”.

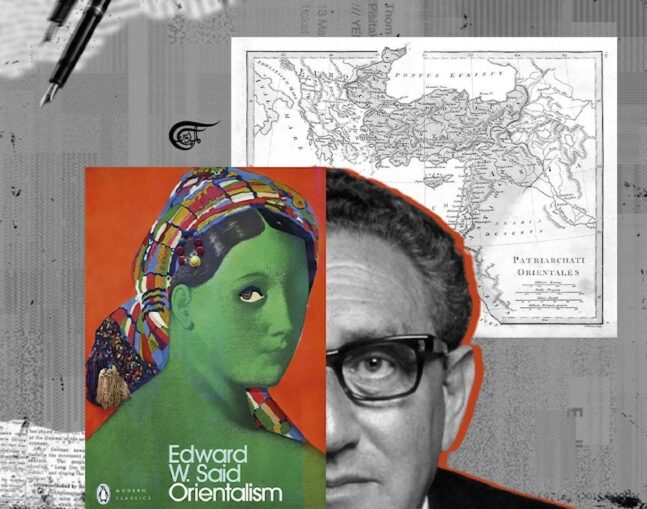

In his famous book on Orientalism, Said therefore describes the theoretical basis from which the former American Secretary of State started to look at, and relate to, the world beyond the West. Said is keen to highlight that Kissinger does not differ much from the Orientalist thought that preceded him – and which he actually embodied par excellence – proposing a criterion that is entirely analogous to that which traditional Orientalists used to distinguish Orientals from Westerners. And just like the distinction made by the Orientalists, the one advocated by Kissinger has an evaluative component, despite the apparent neutrality of the tone.

According to Kissinger, Westerners are “deeply devoted to the idea that reality is external to the observer, that knowledge consists in collecting and classifying information, as accurately as possible.” The proof is, according to Kissinger, that the Newtonian revolution did not take place in the Third World, as he himself explains in the essay Domestic Structure and Foreign Policy: “The cultures that escaped the first impact of Newtonian thought have retained the point of view, substantially pre-Newtonian, so reality would be almost completely internal to the observer”. Kissinger’s theorem is, therefore, satisfied only if we accept, as a postulate, the fact that human beings are, by nature, mentally different from each other.

For Europeans – especially English and French – who tried to describe the East in the 19th and 20th centuries in a more or less “scientific” way, categorizing it through the use of Eurocentric preconceptions, the first obstacle to overcome was that of space-time distance with their object of study. Every journey to the East was a journey not only in space, but also in time. People traveled to the East to understand their roots, especially in relation to the biblical genealogy of Judeo-Christian culture, and this allowed Europeans to think that the further they moved away from the “true world”, Europe, the further they moved away from the present, going back in time to discover the world’s ancestral secrets.

Clearly, this is not the case, the East is nothing more than a geographical space inhabited by peoples with different cultures, languages and religions, without some mythological-esoteric secret about the origins of the world. Despite this, Europeans preferred to take refuge in their preconceptions of an East “distant in time and space”, seeing it as a world apart, not progressed, barbaric, which needs help to be accompanied toward progress and cultural enlightenment, represented by European culture. Westerners preferred (and still prefer) to see and experience the East by orientalizing it, essentially making it the immobile theater of the West, waiting for the pen and dramaturgical genius of the latter to animate and civilize itself.

The East is, therefore, at the same time – like a parent – the foundation and the ideological precursor of the West which the latter must overcome to manifest itself in its full identity. And the West, like a child, is required to re-educate the parent – who, according to the child’s diagnosis, is suffering from clear senile dementia – helping him to overcome his old traditions, even at the cost of forcing him against his will because, in his vision, only he understands the real needs of the latter and has the task and moral obligation to do so.

This moral role arises above all from centuries of identity crisis and the sense of terror that the West has felt towards the imagined East (symbolized above all by Arab-Islamic culture). And this is why the West is now keen not only to re-educate those who educated it, but to do so in the most humiliating way possible, ridiculing them either with an attitude of cultural supremacy or with a pietism fueled by a good dose of white savior complex (modern evolution of Kipling’s concept of the white man’s burden).

African-American writer James Baldwyn explained that Westerners can’t “help but feel that there is something you can do for me. That you can save me. And you still can’t understand that I have put up with your ‘salvation’ for so long I can’t take it anymore”.

It is here that the Western inferiority complex hides, that is to say in intrinsic racism in its ways of approaching other cultures, an approach that governs its relationship, whether direct or indirect, with the East. Between the Orientalist description of the East and its education, there is therefore an intermediate step that should not be overlooked: that of the domination of the Other. Orientalists’ priority was, first and foremost, to describe the Orient in a way that could be made comprehensible to their own intellectual categories.

Therefore, the conceptual and not only physical possession of the Orient occurred. As they say, history is written by the victors, and, dare I say, the Orient is written by Westerners, making it, in fact, their Orient, which exists nowhere other than in their minds, in their books, in their academies, and in their collective imagination.

This relationship must be broken, and it is necessary to build in its place genuine links between different cultures, mentalities, approaches, and points of view, without that attitude of cultural superiority which, a priori, pollutes the relationship itself, making it a relationship between unequals, therefore destined to failure.

I would like to share an emblematic quote that fully represents the feelings of many European citizens of migratory origin who, like me, have experienced recent times in the light of an inner rediscovery. The Senegalese filmmaker Ousmane Sembène, when asked if Europe would understand the message he wanted to convey with his art, explained: “Europe is not my center. My future does not depend on Europe at all. I would like it [the West] to understand me, but it makes no difference to me [whether it will or not]. Why do you want me to be the sunflower that turns towards the sun? I myself am the sun”.

Apparently, then, Kissinger was right about one thing: Westerners are “deeply devoted to the idea […] that knowledge consists in gathering and classifying information, as accurately as possible.” But what he did not understand is that the “truth” almost always depends on the judgment of scholars rather than on the objective material available, and that the reality it talks about is, ultimately, internalized by Westerners themselves who, apparently, have never fully understood the real meaning of the Newtonian revolution that Kissinger proudly uses as a distinction between civilizations.

https://english.almayadeen.net/articles/blog/kissinger–orientalism-and-the-other