The authors, through a silent journey backwards, without explicit references to the great and small moments of the resistance, try to convey the reasons why the Zapatista uprising did not remain a utopia.

In the early nineties, while capitalism in our European geographies appeared as a panacea, commodification and consumption as the only models of life, while resistances (from the left and not only from the left) seemed less convincing and inspiring, the Zapatista movement appeared in Chiapas, men and women who demanded the radical, the obvious: “everything for everyone.” They spoke of the social injustice that went by the name of neoliberalism and, at the same time, through their “intergalactic” appeals, asked us to unite to resist the common enemy, something they continue to do to this day.

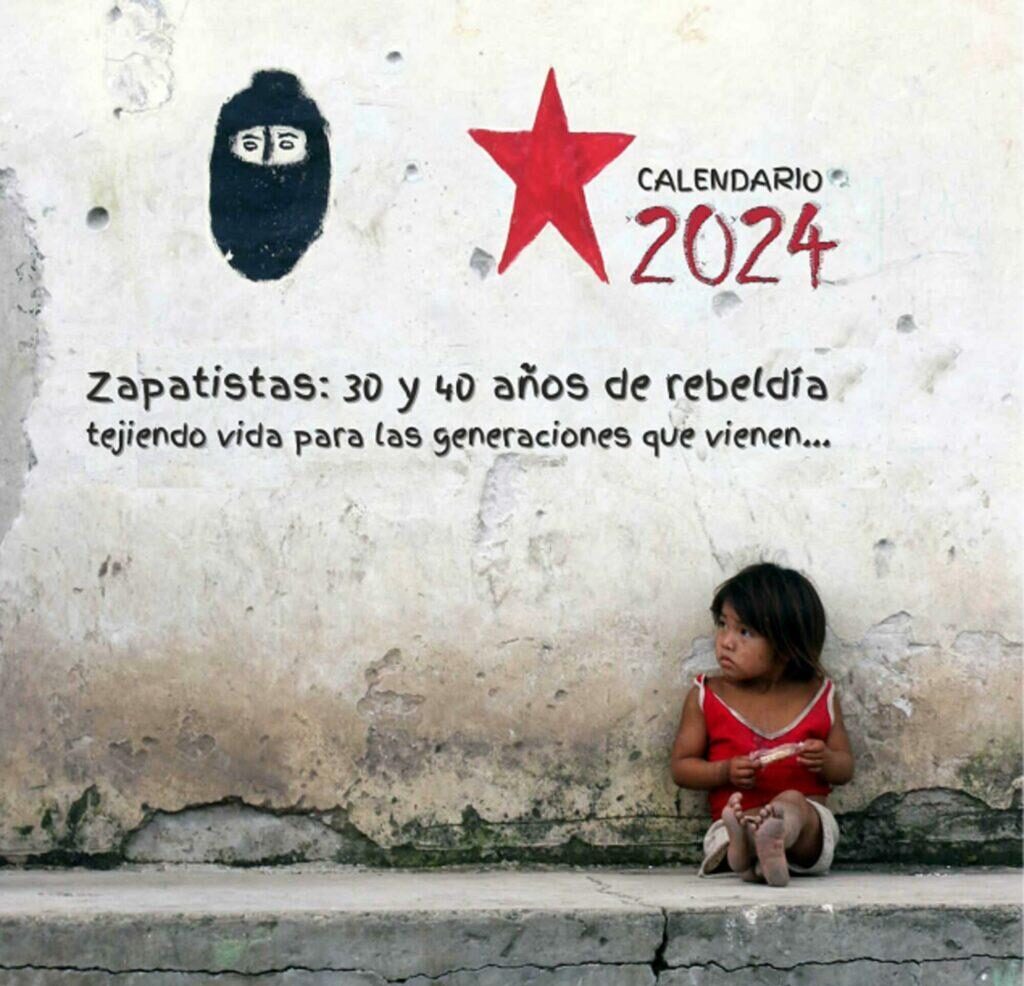

It would have been difficult to foresee back then that 30 years after the uprising and 40 years since the founding of the EZLN, that the Zapatistas could still be there, fighting with persistence, creativity and dignity against capitalism. The “inevitable” fatigue, demobilization or regression that follows any medium or long-term confrontational collective action is not the case in their case. On the contrary, they continue with determination, collective responsibility and organization planning for seven generations ahead. It is very interesting to understand why this deterministic prediction of the weakening, erosion and eventual disappearance of their movement – so expected by all the administrations in Mexico – has not been borne out for a single moment over the years.

We will try, through a silent journey backwards, without explicit references to the great and small moments of their resistance (after all, there are many) – without references to heroes and heroines – to try to grasp the reasons why the Zapatista uprising did not remain a utopia. That is to say, to talk about what we have learned from them, which explains to a great extent the reasons for their resistance and our solidarity with their struggle and with what was born after the uprising of January 1, 1994. An uprising that seemed unthinkable then, as every uprising seems unthinkable today.

Following the traces of their path, their words, their collective action and the organization of their autonomy over the years, as they reach us – filtered, almost inevitably, through our own political vision and the ways in which we resist the barbarism of capitalism – we feel above all the need to express our deep gratitude for what we have learned from them. They are for us a constant source of inspiration and, at the same time, a 30-year challenge to join them in the common struggle against capitalist barbarism. Because we consider ourselves and are part of “that collective heart” that fights against exploitation, repression, looting and contempt for the humble.

From this starting point we locate five key points, five reasons why the Zapatista movement continues to be so alive and so valid: the cosmovision, the practice, the ways, the word and the self-criticism of the communities. These keys are decisive in our own struggles. Despite our different ways of speaking and resisting, despite our different histories, their calls – poetic and playful – have opened channels of communication over the years, so that their thinking feeds ours, their action penetrates ours, their collective responsibility and resistance provokes our inertia, and their discourse breaks the certainties and rigor of our political discourse.

Worldview

Their cosmovision has life, nature and humanity as its priority, and is realized through the collective step of small polyglot communities. In the face of destructive capitalism that turns everything into merchandise – people, land, water, mountains – in search of the greatest profit here and now, the Zapatista communities fight for a balanced coexistence of man and nature, giving another dimension to time and, ultimately, to life itself. This collective step is not limited to the liberated lands of Chiapas, but gives space to the indigenous peoples of Mexico through the National Indigenous Congress (CNI), to defend their struggle against agro-industrial, mining, energy or tourist accumulation on their lands throughout Mexico. A difficult but necessary struggle in the face of the aggressive megaprojects of the rulers and their companies – the Mayan train, for example – as occurs in our geography and in all the geographies that struggle against mining, the diversion of rivers, wind turbines, the destruction of forests, etcetera.

Autonomy

Autonomy in practice, a product of historical experiences and collective political imagination, has demonstrated for thirty years that when peoples do not follow party mechanisms, do not accept the State as the great benefactor, nor embrace the unique truth of God and the Patriarch, they do not necessarily end up in resignation and disappearance. On the contrary, in the Zapatista communities the conditions for a dignified life are built day by day, autonomy is strengthened through collective work and co-responsibility, and community ties are strengthened as a way of life based on the care and cultivation of the land.

The creation of the Caracoles and the Good Government Councils in 2003, in addition to the autonomous structures of health, education, justice, the already existing agricultural cooperatives, emerged from dialogic processes, as well as the new form of the commons, the “Land without papers.” The collective sharing and tending of lands recovered by Zapatista peoples together with non-Zapatista peoples was recently born out of the same processes. In these structures of Zapatista autonomy everyone can work in education for a time, then on the land, then in the hospital, according to needs, community values and collective goals, rather than self gain. Within these interdependent frameworks of principles, rules, practices and institutions, independent of the state as learning processes, personal and social action takes on meaning and value to the extent that they ensure life today and tomorrow.

Women play an important role in sustaining autonomous structures. The strengthening of women’s political-social action, closely linked to the construction of autonomy, is conquered in practice with and against the traditions of indigenous peoples and is expressed through an experienced political discourse. “Without women, this struggle would not be for the people but for men,” they stress, considering that changes in women’s lives are not a secondary element of their struggle. Evidently, it involves confrontations with the conservative ideas and patriarchal morals of men – fathers, husbands, partners – rooted in the indigenous communities for more than 500 years. The companionship, collective work and courage of the women manage to break down the triple slavery of class, race and gender in which they live and create one of the few places in the world where no femicide has been recorded for many years. A place where women can feel happy and safe. The importance of the Zapatista women’s struggle becomes even greater if we take into account that Mexico registers an average of ten femicides a day, that is, seven out of ten women in the country have suffered violence at least once in their lives.

Ways of doing

The Zapatista ways, since their emergence, and especially what followed January 1, 1994, reversed much of what we had known until then. Precisely because the insurrection and the Zapatista movement in general managed to bring together elements that were contrary or absent in the history of struggles. It brought to the forefront ways of thinking, expressing and organizing the armed struggle, the construction of autonomy and the articulation between the two. This is very different from previous revolutionary historical paradigms, they are forms that are firmly oriented towards life and not towards a politics of death.

The Zapatista insurrection is carried out by a guerrilla movement that “abhors bullets,” does not seek death and speaks tenderly of its dead in time, because, as they have told us in several of their communiqués, the dead have accompanied their steps since the first years of their struggle (1984-1994) when the time and form of the insurrection were still being prepared. The Zapatistas often refer to the importance that memory has for them, underlining that the worst possible death is death by forgetting. This endearing relationship, “conversation” and learning with the dead as part of collective organizational planning in the present was hitherto absent from the history of various movements around the world. Until its appearance, the dead heroes of past uprisings were vindicated through future struggles, the resistances of the present must – among other things – pay homage to the struggles of ancestors, but always in different historical times.

Until then, the idea dominated that the more heroes and heroines an insurrectionist struggle had, the more important and great it would seem. So, a guerrilla whose soldiers carry wooden weapons, identify themselves as “shadows of a tender rage” who “fight for the privilege of being a seed under the earth” and “march dancing,” breaks the insurrectionist norms as they have historically been configured in the struggles of those from below. Much more, it breaks with militant and harsh stereotypes when the army waits for entire polyglot communities – women, men, children – to decide whether or not to go to war, when it proceeds by “listening and commanding by obeying.” All of the above is aptly summarized in the sign at the entrance to Oventic: “You are in Zapatista territory. Here the people command and the government obeys.”

Their word through communiqués

The word of their communiqués and their appeals, as another way of seeing things, is essential in their struggle. It does not “adorn” their actions, but is an intrinsic element of their way of doing politics. The “poetics of insurrection” not in literary, but primarily philosophical terms, does not detract from the role of organization and responsibility, it does not take people away from organized struggle. It is a language that sharpens in action, and this in turn sharpens action. It is a discourse that opens perspectives in a suffocatingly closed world, which affects the gaze of those at the bottom wherever they are. A typical example is that where we used to speak of time and space we now refer to “calendars and geographies”. The change seems minimal, but it is significant if we take into account that the calendar is a discourse about time and geographies are a writing (discourse) about space that drives movements to unite “and what is from here and what is from there cease to be from here and there, and become, at last, a bridge that defies calendars and geographies.”

Self-criticism

It is difficult to imagine the movements of our geography entering into a process of self-criticism through which they can synthesize and create something new without falling into a process of dismantling and de-massification. Perhaps this element, so rare or so non-existent in our own resistances, is for us what is most necessary. Our movement initiatives tend to get lost in silence, unlike the silences and reflections of the Zapatistas who “fervently wish to become the future.” Very early on, a few days after the uprising, the Zapatistas spoke of errors on the part of the EZLN, of “errors and excesses of the compañeros in the insurgent territories. Similarly, both immediately after the creation of the Good Government Councils (2003) and 20 years later (2023), the mistakes and failures that almost inevitably occur “when entire peoples learn to govern” are recognized, when a school is built to understand how to govern, which in the long run will give birth to a new way of doing politics. This process of courageous self-criticism has recently led to the dissolution of the Good Government Boards and the creation of “the commons” and “non-property.”

All of the above shows us why the rebellion did not remain a utopia, even if “whatever is missing is missing.” In the dark times we live in, where resistance is discouraged, wars multiply and capitalism becomes more destructive than ever, the Zapatista autonomous communities are an oasis, a hope and a challenge for us to aspire to meet.

Original text by Geppaki Anastasia and Papazoglou Sokratis, members of the Greek Collective “Calendario Zapatista” in El Salto, July 7th, 2024.

Photos by Calendario Zapatista.

Translation by Schools for Chiapas.