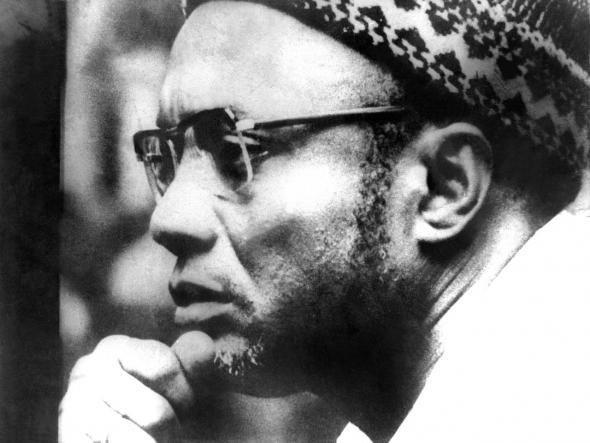

He is an important figure of the African revolution who would have turned 100 on September 12, but his life ended in 1973 due to his assassination at the hands of Portuguese colonialism. Amílcar Cabral left his mark on the history of the African continent. Diagne Fodé Roland pays tribute to him and stresses that the legacy of this great thinker is still relevant today.

Outraged by the Portuguese fascist colonial oppression, especially after the successive famines that caused 50,000 deaths between 1941 and 1948 in Cape Verde, Amílcar Cabral decided to train in agronomy with the aim of helping peasants and studied agricultural engineering until 1952 in Lisbon, capital of Portugal.

There he met student activists for the liberation of the African colonies from Portuguese imperialism. With these activists of the independence struggle in western and southern Portuguese-speaking Africa, such as Agostinho Neto (MPLA), Eduardo Mondlane of FRELIMO, etc., they clandestinely created the Center for African Studies to promote the culture of colonized black peoples and collaborated with the Portuguese Communist Party (PCP) (also clandestine). These future leaders were trained in scientific communism and decided to found the anti-colonial liberation movements in their respective countries.

Cabral decided to resign from his position as a researcher at the Agronomic Station of Lisbon (Portugal) to work as a second-rate engineer in Guinea, where he was responsible for the agricultural census that allowed him to identify the nationalities and social classes that made up Guinea.

In 1954 he created a nationalist political organization in Bissau under the pretext of promoting cultural and sports activities. This association was banned by the Portuguese colonialists and Cabral was expelled from his own country to settle in Angola, where he coordinated tasks for agricultural companies.

These investigations and studies of the peasantry under colonialism allowed him to apply dialectical and historical materialism, and to develop his own analysis of colonial society by adapting scientific communism to African realities.

In 1956, after being authorized to return once a year to Guinea-Bissau, he clandestinely founded the PAIGC (African Party for the Independence of Guinea and the Cape Verde Islands) of which he was appointed secretary general.

After the fascist colonial massacre during the dockers’ strike in 1959, the PAIGC opted in 1963 for armed combat and fought against the Portuguese army on several fronts in the neighboring countries, Guinea Conakry and Casamance, province of Senegal.

The PAIGC quickly controlled 50% of the territory in 1966 and 70% from 1968 onwards, and created a political-administrative organization in the liberated areas, the characteristics of which Cabral explains as follows: “The dynamics of the struggle require the practice of democracy, criticism and self-criticism, a greater participation of the population in the management of their lives, literacy, the creation of schools and health services, the training of leaders of peasant and worker origin, and many other achievements that imply a real forced march of society along the path of cultural progress. This shows that the struggle for liberation is not only a cultural fact, but also a cultural factor.”

Cabral developed a detailed analysis of the national realities and contradictions of Guinean and Cape Verdean society in order to determine the national and social groups most capable of engaging in the struggle against colonialism.

In 1961 he was a representative of the liberation movements of the countries colonized by fascist Portugal during the Third Conference of African Peoples that took place in Cairo. Starting from the Leninist formula of “concrete analysis of each concrete situation”, he explained that the struggle must “strengthen the means of action […], develop effective forms and create others, on the basis of knowledge of the concrete reality of Africa and of each African country, and of the universal content of the experiences acquired in other environments and by other peoples”.

Cabral teaches us that nationalities and social classes must be studied based on the fact that “people do not fight for ideals or for what does not interest them directly; people fight for concrete things, for better living conditions in peace and for the future of their children. Liberty, fraternity and equality are empty words if they do not mean a real improvement in the lives of people who struggle.”

Cabral combined the ideological and political-military struggle with the diplomatic struggle to achieve recognition of the battle for anti-colonial liberation on an international scale. In 1972, the UN recognized the PAIGC as “the true and legitimate representative of the peoples of Guinea and Cape Verde.”

Cabral was also the “ambassador-spokesman” of the national liberation movements of the Portuguese colonies in various African and international forums. He was the undisputed leader, especially at the Tricontinental conference where he took the floor on January 6, 1966 in Cuba to present his revolutionary theory of African national and social emancipation: “We do not fight simply to put a flag in our country and have an anthem, but so that our peoples are never again exploited, not only by the imperialists, not only by the Europeans, not only by white-skinned people, because we do not confuse exploitation or the factors of exploitation with the skin color of men; we don’t want there to be more exploitation in our country, not even by black people.”

Acknowledging both the internationalist role of Cuba and the pan-African role of independent Algeria for its active solidarity with all liberation movements in Africa, he declared: “Christians go to the Vatican, Muslims to Mecca and revolutionaries to Algiers.”

Unfortunately, Amílcar Cabral was assassinated on January 20, 1973 in Conakry by Portuguese colonialism that used agents infiltrated in the military branch of the PAIGC to commit this crime, which prevented the true father of independence from experiencing the birth of the State of Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde proclaimed on September 10, 1974.

Hero and martyr of the first phase of African liberation, Cabral should serve as an inspiration for the current generation of fighters for the second phase of the national, pan-African and social emancipation of the peoples of Africa.

Source: Rebelion.