The Revolutionary Foundations of Our Americas

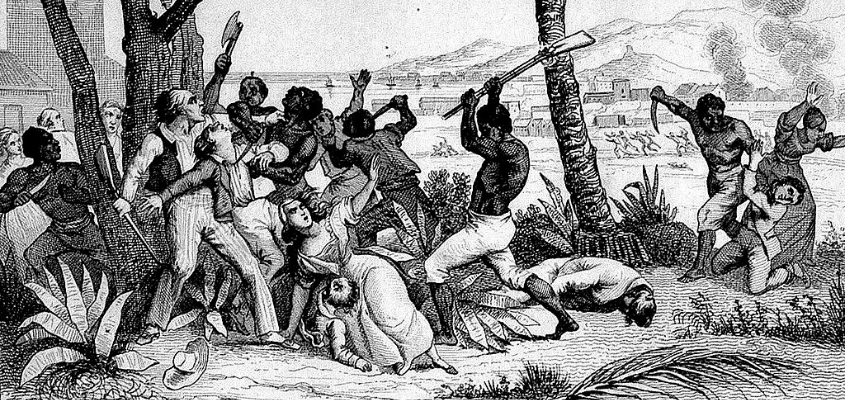

On April 8, 1804, a few months after leading Ayiti (Haiti) to independence after a bloody 13- year revolutionary war against European enslavers and colonists, the new nation’s leader, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, articulated the most radical vision of freedom in history. In the proclamation, ‘Liberty or Death,’ Dessalines pronounced “I have avenged America,” decrying the barbarity and violence of racist Europeans. At the same time, he delineated a vision of a new Ayiti, and the world, based on sovereignty, dignity, and respect.

On January 1,1891, 87 years after Dessalines’s proclamation of an independent Haiti, and exactly 62 years before the triumph of the Cuban Revolution, José Martí published his famous work : Nuestra América or “Our America.” In this, Martí called for Latin America to unite against ongoing colonialism and in protest of U.S. domination through the Monroe Doctrine .

On December 10, 1963 in Detroit, Michigan, Malcolm X delivered his “Message to the Grassroots” speech where he criticized the Civil Rights Movement’s appeals to U.S. white supremacist foundations, individualism over grassroots organizing, and the failures of Black/African peoples in the U.S. to unite with the anti-colonial movements of the Global South. Significantly, Malcolm demanded more than “civil rights” for Black/African peoples in the U.S.; he called for true and complete human rights that would be the basis for the liberation of all African peoples globally. In this sense, Malcolm also urged us to reject the idea that the political identity of Black/African people is tethered to the U.S. settler project, proclaiming “[we are]… not ‘Americans’. We are victims of Americanism.”

All three of these visionaries died waging the struggle for liberation in the Americas. Dessalines was betrayed and assassinated two years into Haiti’s independence, a victim of the unresolved contradictory ideologies that fractured the nascent nation with tragic consequences. Martí, the writer and organizer, would die in battle in the struggle for Cuban independence. While Cuba would win flag independence in 1902, it would not escape the direct neocolonial chokehold of the U.S. and its corporate vultures until the revolution of 1959. Malcolm was slain by reactionaries and counterintelligence operatives in 1965, crippling the movement for Black/African liberation within the U.S.

In the ensuing years, and despite continuing resistance through individual and mass struggles, the promise of liberation has yet to be realized. Moreover, Malcolm would likely be disappointed with our failures, especially in the U.S., to carry on the vision of a Black/African struggle that is anti-colonial, Black nationalist, and internationalist.

Yet Malcolm’s words on that cold December day in Detroit still ring true. Like Martí, who called for Latin American unity, Malcolm argued for unity against a common enemy, calling for a revolutionary anti-colonial struggle of all African and colonized and oppressed peoples against white supremacy and imperialism:[1]

We have this in common: We have a common oppressor, a common exploiter, and a common discriminator. But once we all realize that we have this common enemy, then we unite on the basis of what we have in common. And what we have foremost in common is that enemy — the white man. He’s an enemy to all of us…In Bandung back in, I think, 1954, was the first unity meeting in centuries of Black people. And once you study what happened at the Bandung conference, and the results of the Bandung conference, it actually serves as a model for the same procedure you and I can use to get our problems solved…These people who came together didn’t have nuclear weapons; they didn’t have jet planes; they didn’t have all of the heavy armaments that the white man has. But they had unity….They began to recognize who their enemy was. The same man that was colonizing our people in Kenya was colonizing our people in the Congo. The same one in the Congo was colonizing our people in South Africa, and in Southern Rhodesia, and in Burma, and in India, and in Afghanistan, and in Pakistan. They realized all over the world where the dark man was being oppressed, he was being oppressed by the white man; where the dark man was being exploited, he was being exploited by the white man. So they got together under this basis — that they had a common enemy.

It is this perspective that would, towards the end of his life, push Malcolm to form the Organization for Afro-American Unity, a Pan-Africanist revolutionary project.

Malcolm’s understanding of militant grassroots struggle, self-defense, and uncompromising principles are key to the Black Radical Peace Tradition that underlies the work of the Black Alliance for Peace (BAP). While we take inspiration from the struggle of these heroic ancestors, we know that this struggle is far deeper and broader than the actions of individual men. This work is fundamentally about building collective power to oppose and defeat the militarization, repression, destabilization, subversion, and permanent war against our peoples. As our ancestor, and former Black Panther and political prisoner Safiya Bukhari reminds us , in order to engage in the battle against imperialism and build a new society, we must also revolutionize our collective practices and consciousness through our political programs.

In building collective power, we see it as critical to link the unifying compass of Martí’s “Nuestra América” with the militant struggle of the Black Radical Peace Tradition, and the fire of Dessalines call to avenge the Americas. “Nuestra América” is the call of revolutionary forces in the Americas to rally all the historically oppressed peoples of the region against colonialism and imperialism by claiming one contiguous land mass stretching from Canada to Chile. In understanding the political, social, and economic position of working class Black/African peoples in the United States as united with the working peoples of the Caribbean and Latin America, we take inspiration from “Nuestra América” and push for the liberation of “Our Americas”.

Our first step is to recognize that working class Black/African and Brown peoples of Latin America, the Caribbean, and within the U.S. have a common enemy that seeks to exploit and dominate the region. Our joint struggle is to defeat this enemy by attacking its various forms of domination – (neo)colonialism, patriarchy, capitalism, and imperialism. The second step is to organize ourselves to build meaningful alternatives to this domination that are based on popular sovereignty, collective self-determination, and human dignity. Both steps require an Americas-wide consciousness toward collective, grassroots, anti-imperialist struggle.

De facto Colonialism in the Americas

In the first month of Donald Trump’s second term as President of the United States, he and Secretary of State Marco Rubio proclaimed that U.S. will recapture the Panama Canal and annex Greenland and Canada; publicly threatened Mexico, Colombia, and Canada with tariffs; and all but declared war on Cuba, Venezuela, and Nicaragua – calling them “enemies of humanity” for refusing to capitulate to U.S. interests. Rubio also visited Panama, El Salvador, Guatemala, Costa Rica, and the Dominican Republic on a tour aimed to strong-arm these nations into strengthening ties with U.S. corporate and military interests and severing developmental agreements with China.

But the brute tactics of the Trump regime, in trying to ensure U.S. “Full Spectrum Dominance” in the region, are not exceptional. “Full Spectrum Dominance” is the bipartisan doctrine articulated clearly in the Pentagon’s “Joint Vision 2020” paper that commits the U.S. to exercising military, political, and economic control across the globe to protect imperialist investments and interests – a stance that requires aggressively countering any threats, real or imagined, to its dominance. Trump’s regime, therefore, is building on the foundation laid by the U.S. duopoly’s economic and political agendas of exploitation and domination.

It was not Donald Trump who initiated the current U.S.-led occupation and anti-democratic transition process in Haiti, or who recognized (for a second time) a sham President of Venezuela , or who provided U.S. military support to the right-wing narco-capitalist government of Daniel Noboa in Ecuador. These violations of national sovereignty in our region, and more, occurred through the Biden White House and Blinken State Department. Just as it was also not the Trump regime that oversaw the repression of the Stop Cop City movement and the Student Intifada in response to the U.S.-Israeli genocide on Gaza. Again, this was the Biden-Harris regime and the mayors of the U.S.’s largest cities, almost all of whom are Democrats. Even Trump’s decision to send deported immigrants to Guantanamo Bay, a military base which the U.S. has occupied in Cuba since 1903, is just making good on a thr eat that Biden issued in 2024 . And Biden’s declaration was simply a revival of Bush Sr. and Clinton’s use of Guantanamo to hold captive Haitian migrants.

Nevertheless, the current actions of the Trump regime have a different character. The U.S. has reverted to its brazen call for colonialist expansion, including full military control of the hemisphere, aggressive economic coercion, and divide-and-rule tactics – all wrapped up in vulgar white supremacist nationalism. The U.S./EU/NATO Axis of Domination is now more open and defiant!

The tools of this Axis of Domination are clear: military domination through the U.S. Southern Command (Southcom); economic warfare through sanctions, tariffs and other unilateral coercive measures; continuation of corporate extractivism over national development; and usurpation of state sovereignty through policies as the Global Fragility Act. And, of course, U.S. imperialism also depends on a captured class of neocolonial compradors (e.g., William Ruto in Kenya, Luis Abinader in the DR, Daniel Noboa in Ecuador, and Nayib Bukele in El Salvador) who work to uphold its Full Spectrum Dominance. Indeed, the Americas region remains under de facto colonial rule. And, despite years of anti-colonial resistance throughout the hemisphere, the current bold articulation of U.S. power seems calibrated to accelerate this full spectrum dominance while simultaneously attempting to paralyze and demobilize legitimate united resistance.

Black Struggle in the Heart of Empire

We understand that Black/African communities in the U.S. hold a unique position in the heart of empire. With a long and relentless history defined by enslavement, economic exploitation and underdevelopment, political subjugation, environmental degradation, and state violence, these communities suffer the brunt of domestic white supremacist domination. Black/African organizers and scholars have described the Black/African condition in the U.S. as akin to a colonial relationship. Robert Allen, for example, understood the colonial relationship in these terms: “[the] direct and over-all subordination of one people, nation, or country to another with state power in the hands of the dominant power.” In this case, white supremacist, capitalist power with direct control over Black/African peoples and communities. Economist William Tabb agreed with this and outlined the conditions faced by Black/African people in urban ghettos in the 1970s: a lack of labor freedom, suppressed wages, disposability and vulnerability of labor, and dependency on external aid (welfare) and political power (patronage) at the price of comprising collective needs.

This analysis of the internal colonization of Black/African people comes from a long and rich tradition of struggle and scholarship, outlined comprehensively by many including Harry Haywood and later Claudia Jones , Kwame Ture , and Robert Allen , as well as organizations as diverse as the Communist Party USA, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the Black Panther Party, the Republic of New Africa, and the League of Revolutionary Black Workers. As scholar Charisse Burden Stelly details in Black Scare/Red Scare, Haywood and other Black communist organizers conceptualized the Black Belt Nation Thesis in the 1920-40s, understanding Black peoples predominantly residing in the U.S. South (the “Black Belt”) as an internal colony with the right to national self-determination. After the second imperialist world war, Jones laid out the distinctions between Black populations in both the North and South, while furthering the analysis that all Black people represented a nation within the borders of the U.S. – a community of people with common language, economic life, and culture – all under assault by the racist U.S. state.

While the “internal colony” model is an important way to understand the position of Black/African communities in this white supremacist country, we must also acknowledge how class dynamics of the U.S. Black/African communities have continued to shift over years. Bruce Dixon, for example, asked us to come to terms with the reality that, “Today there are thousands of actual black people in the actual US ruling class…There are black lobbyists and corporate functionaries…the two dozen or so black admirals and generals…There are black media figures…and black near billionaires success stories are built on low wage viciously exploited black labor…”. We agree with Dixon in recognizing the Black compradors aiding and abetting U.S. white supremacist domination. Nevertheless, we think it imperative to assert that the majority of our Black/African communities are poor and working class, and bear the brunt of the domestic side of U.S. imperialist terror.

In 1969, Robert Allen predicted that, after the Black revolts of the late 1960s, a “neocolonial re-direction” would occur that would continue to subjugate the majority of Black people in the U.S. This re-direction would replace direct white rule and power over the internal colony with Black comprador intermediaries (e.g., national politicians, mayors, corporate executives and managers) who would be more palatable to the people they dominated. This follows the analyses of Kwame Nkrumah , Amilcar Cabral , Stephanie Urdang , and others on neocolonialism on the African continent. Allen argued that regardless of colonial or neocolonial rule, only a true and comprehensive anti-colonial struggle could lead to liberation for Black people in the U.S. This would require an economic program on a national level and the proliferation of international solidarity with ‘Third World’ peoples to defeat imperialism. For Allen, like for Malcolm, this would be a Black struggle that is anti-colonial and internationalist[2]:

[T]his struggle would aid materially in breaking black dependency on white society…The establishment of close working relationships with revolutionary forces around the world would be of great importance. The experiences of Third World revolutionaries in combating American imperialism could be quite useful to black liberation fighters. For the moment, mutual support between Afro-American and Third World revolutionaries is more verbal than tangible, but the time could come when this citation is reversed, and black people are well advised to begin now to work toward this kind of revolutionary, international solidarity.

In this sense, we link the struggles of the Black/African poor and working masses both to other marginalized communities in the U.S., and to all colonized and marginalized peoples’ globally.

This means the need to join the other liberation struggles of the colonized in the U.S., including Native peoples and lands, as well as the people of Puerto Rico, Guam, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. The framework of internal colonialism helps us see that the Black/African liberation struggle is not simply against racism or a pursuit of state-sanctioned civil “rights.” Instead, together with the global majority, we are engaged in a struggle for self-determination and sovereignty against a common enemy. We have a common struggle of liberation against empire.

For BAP, like for Malcolm, ours is a struggle for liberation, comprehensive human rights, and dignity – or what we call People(s)-Centered Human Rights [3]. This is, for us, an anti-colonial struggle, and a movement of solidarity, and collective resistance.

Where do we go from here?

In outlining necessary actions for Black radicals in 1969, Robert Allen asserted that “the continuing main task for the black radical is to construct an interlocked analysis, program, and strategy which offers black people a realistic hope of achieving liberation.” Any road to liberation requires challenging, disrupting, and defeating imperialism, domestically and globally. In terms of building a program to support radical and revolutionary struggle in “Our Americas”, we learn from freedom fighter Assata Shakur and the BLA who knew that any revolutionary struggle in the U.S. must engage in meaningful material solidarity with the struggles of the peoples and nations of the Global South.

In this moment, we aim to help advance this solidarity and struggle through the development of the U.S./NATO Out of Our Americas Network – a mass-based, people(s)-centered, anti-imperialist structure to support the development of an Americas-wide consciousness, facilitate coordination of our unified struggles and build from the grassroots a ‘Zone of Peace ’ in Our Americas. Along with BAP’s recently inaugurated North-South Project for People(s)-Centered Human Rights , the Network and the broader Zone of Peace campaign are efforts that consciously joins the Black/African liberation movements with the struggle for true popular sovereignty, self-determination, and decolonization in the Americas and globally.

This Network is a component of the collective Campaign for a Zone of Peace in Our Americas , which calls for an activation and coordination of grassroots movements and organizations to expel from our region the structures of U.S.-led imperialism that generate war and state violence—colonialism, patriarchy, capitalism. This campaign’s vision of “Peace” follows BAP’s principle of the Black Radical Peace Tradition :

Peace is not the absence of conflict, but rather the achievement by popular struggle and self-defense of a world liberated from the interlocking issues of global conflict, nuclear armament and proliferation, unjust war, and subversion through the defeat of global systems of oppression that include colonialism, imperialism, patriarchy, and white supremacy.

Achieving a lasting, durable peace in Our Americas requires deepening our coordination, internationalizing our grassroots struggles, resourcing our efforts toward effective solidarity, and growing our capacities for resistance.

We know that advancing the revolutionary consciousness of the people of Our Americas is a necessary foundation for the grassroots struggle for our sovereignty, self-determination, and dignity. We know that struggling in Nuestra América through the Black Radical Peace Tradition necessitates centering the ongoing resistance of the people of Haiti, defeating the neocolonialism that has co-opted unity and integration in the Caribbean, and supporting those nations fighting to assert their sovereignty and determine their destinies, particularly Cuba, Venezuela, and Nicaragua. We know that we can establish the collective power to oppose the U.S./EU/NATO Axis of Domination.

For our own survival, and the survival of the oppressed masses of the world, we must avenge Our Americas. The time is now.

[1]El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz [Malcolm X]. (1963). Message to the Grassroots. BlackPast. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/speeches-african-american-history/1963-malcolm-x-message-grassroots/

[2]Allen, Robert L. (1969). Black Awakening in Capitalist America: An Analytical History. DoubleDay, New York.

[3] “People(s)-Centered Human Rights (PCHR) are those non-oppressive rights that reflect the highest commitment to universal human dignity and social justice that individuals and collectives define and secure for themselves and Collective Humanity through social struggle.” https://peoplescenteredhumanrights.com/

source: Black Agenda Report