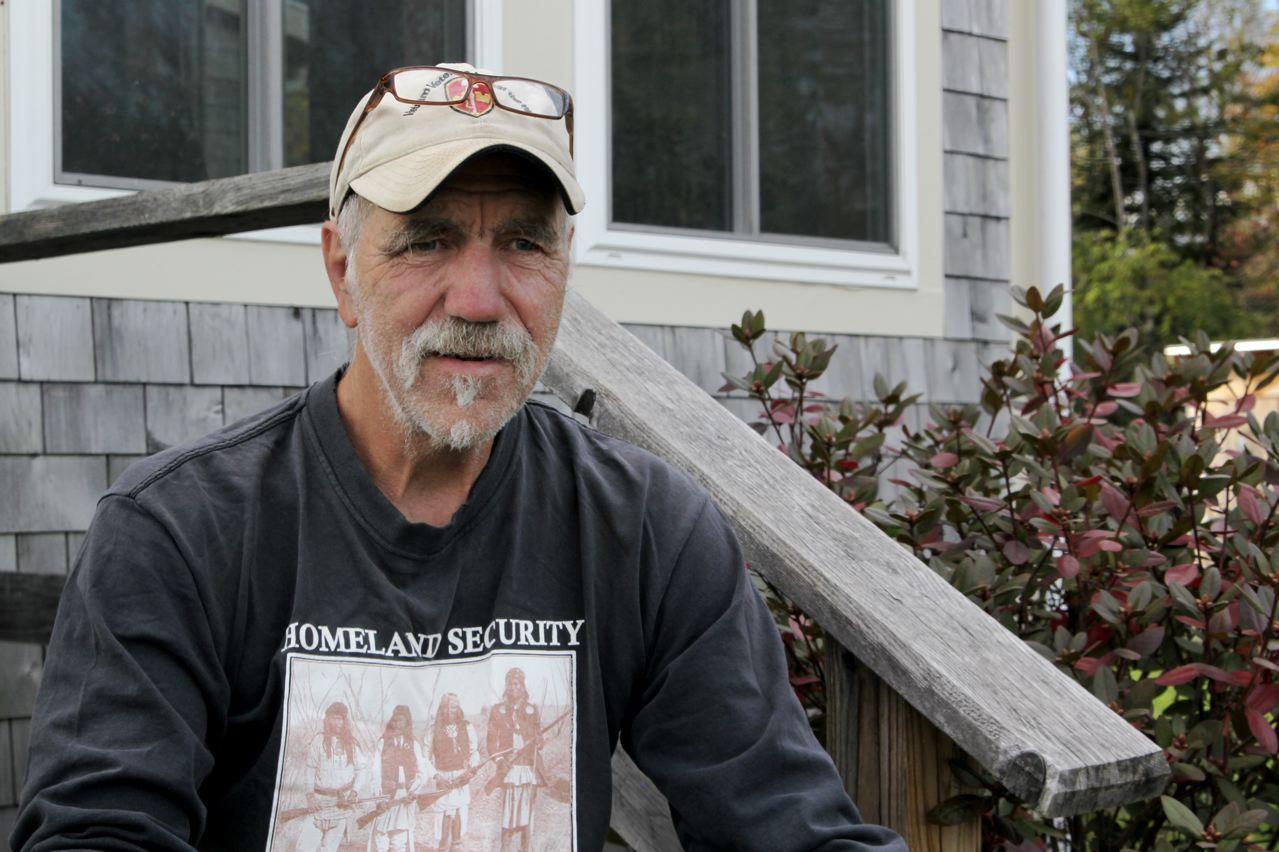

On 16 April 2025, Unity of Fields interviewed Ray Luc Levasseur, a former political prisoner. In 1975 Levasseur co-founded the Sam Melville-Jonathan Jackson Unit, which later renamed itself the United Freedom Front. They carried out dozens of expropriations and anti-imperialist bombings until their capture in 1984, after being on the FBI’s Most Wanted list. Levasseur was sentenced to 45 years and served his time in some of the most brutal and repressive prisons in the country, USP Marion and ADX Florence, including thirteen years in solitary confinement. He was released in 2004 after serving 20 years, and now lives in his home state of Maine. The interview transcript has been lightly edited for clarity.

If you are interested in reading more about Ray Luc Levasseur and the United Freedom Front, we recommend reading Until All Are Free: The Trial Statement of Ray Luc Levasseur and checking out his online archives at UMass Amherst, where you can find many of the documents mentioned in the interview.

Download a zine version to print/fold here.

Editorial disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this interview do not necessarily reflect the views of Unity of Fields.

Unity of Fields: When people nowadays think of anti-imperialist armed struggle in the US, they tend to think of the Weather Underground and the Black Panther Party (BPP), maybe the Black Liberation Army (BLA), maybe the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA). Often people aren’t aware of numerous smaller clandestine formations that were active around the same time, like the one you were part of, the Sam Melville-Jonathan Jackson Unit (SM-JJ), which later renamed itself the United Freedom Front (UFF).

UFF is such an interesting, and, in a lot of ways, quite successful, case study of militancy. You came into revolutionary struggle in a slightly later generation than Weather, and in a different way than the stereotype of white radical elite college student — you were radicalized by serving in Vietnam, serving time in prison for a minor drug offense, and coming from a very working-class background.

Could you speak to how you see UFF’s trajectory in this context, and why you think it is generally less well known? And why is it important for people of younger generations, especially those interested in the question of militancy, to consider?

Ray Luc Levasseur: Part of it is some of these groups were very short-lived, for one thing. They traveled fast, but they went down in flames pretty fast too. It’s been a problem in terms of clandestine groups in this country. I mean, there’s amazing number that just didn’t last very long and took major hits and were pretty much decommissioned. The SLA weren’t around all that long either but one of the big reasons people remember them is because of the significant media coverage of it. But a lot of the other groups didn’t get that kind of media coverage like Weather or the SLA did. I don’t know if that’s class-based or not.

Those of us that I was underground with, we all had some kind of previous political activity in public, but we were not part of big chapters of a national group per se. A couple of us were, I was in national VVAW (Vietnam Veterans Against the War), one of us had been in SDS, but in chapters that were not at the forefront of media attention. I think the George Jackson Brigade was like this too. So people in that particular area where they were operating, you know, would have a better idea of what’s going on, who this was being conducted by, and connect the message to the people where others don’t. A lot of the publicity, a lot of the media coverage is really negative, and part of the purpose for that, was not just in terms of what the general public was reading, but in terms of what political activists were reading.

Clandestinity by its nature, people don’t know who you are and they can be very distrustful. And depending also on the extent of your aboveground support network, not every group has one, but every group should have one. A group like Weather had a really extensive aboveground network and that could be utilized in a lot of ways to promote the cause and build a little support, and certainly awareness and keeping the group front and center in people’s minds politically and personally. We had an aboveground network going under that was eventually decommissioned through police and other methods and then we went through a dry spell and then we started to rebuild another one. That support network eventually collapsed similar to the BLA network that collapsed after the Brinks [Robbery in 1981], and their network was more extensive than ours. That’s a major blow to any group. I know that it played a really significant factor with us, particularly the second time around where it had collapsed. That really contributes to your isolation. That kind of isolation is the enemy of an underground group because it hampers your ability to recruit and do all kinds of things. Essentially it cuts off the logistical network. The kind of support, material and otherwise, political and otherwise, that you might be getting through that aboveground support network all of a sudden just gets shut off. You cut off a supply route and it really has a big impact on even a conventional military force. Look what’s happened in Lebanon when the israelis were really able to dismantle a lot of the network that was supporting both Hezbollah and to some degree Hamas, it’s had a big impact. And the more isolated you get, the less you’re out there. Your voice is diminished somewhat.

I think that when you say the Panthers, you’re really talking about BLA, in terms of more clandestine actions. The Panthers always, or did for a long time, had clandestine networks, but they weren’t there in an offensive capacity, they were more self-defense oriented. They’d have a safe house, they’d have the proper credentials, paper identification, funds, a way for somebody to disappear quickly if the need was there. The BLA actually had things set up more like we had set up, where you’re dealing strictly with people that are underground, have to stay underground, and are carrying the initiative forward. They’re initiating actions. They’re not there in the self-defense mode per se, I dunno if that makes sense. But the two [the BLA and BPP] often get used interchangeably, and the BLA benefited from the huge, huge reputation and media attention that the Panthers had, benefited in the sense of what the question you asked is, why some of these groups are well-known and some are not. So Weather had built its reputation by its involvement with SDS. Then when a significant number of them go underground and become the Weather Underground Organization, they’re already pretty well known. So that’s my thinking behind those two particular organizations. And both were around for a long time, especially when you consider those particular roots, one in the [Black] Panther Party and one in groups like SDS.

UoF: Please correct me if I’m wrong, but based on what I’ve read about the United Freedom Front, it sounds like you guys achieved a huge number of successful actions and evaded capture for longer than many other groups. Is that correct? Why that was the case?

RLL: It is correct. In fact, I think that’s one of our main claims to fame, really, is the length of time we were underground. Because we weren’t just hiding. We were the number one fugitives they wanted in the country. After the first couple years we became number one. As the other groups got picked off or decommissioned in one way or another, those forces of repression can focus more and more on you. Plus we were very active, we were always doing something and they knew it. High-risk stuff. We had developed means that if we had just wanted to be underground just to live away from the eyes and ears of the government, we could have done that indefinitely, because we had the methods down so well. But our justification for being underground was to be active. I wouldn’t be underground if I couldn’t stay active. So we were constantly carrying out actions of one kind or another throughout the whole time, including many close calls. And when you look at groups, even within the BLA itself, which was more extensive than we were, and they were around for a considerable period of time, but individual cells within the BLA, a lot of ’em went down really quick. But they were large enough where they could absorb the loss and keep going.

We were smaller, we couldn’t handle too many hits. You know what I mean? When you go up against the repressive arm of this government, they have all the money, the resources, the manpower, the computer power. They can make mistake after mistake after mistake. I can sit in and talk to you about the strategic and tactical mistakes the FBI and other police made in trying to get us. But because of that foundation, the endless supply of funding and police power, weaponry and intelligence, all of it, they can make mistake after mistake, and just go back to the drawing board and do it again. When you’re a small organization, there’s very little margin of error for you. You can make one mistake and it all comes tumbling down.

Now, to give you an idea in terms of even Weather and BLA, which had had pretty good resources, the Brinks case really was like, if you look at it, it’s like all of a sudden the dominoes started falling. A huge part of their total underground infrastructure just went down around that one action. So you don’t have the room to make those kinds of mistakes. I think it’s really to our credit that we were underground for ten years. I mean, what other group can you see that did that and was politically active for that entire period of time and with a number one target on our backs almost the whole time?

Expropriation was a part of our strategy, and that’s different than certain clandestine formations that got their funding a different way. When you look at Weather, some of that money obviously came from some pretty wealthy family members and friends, that was part of the network, right? There’s a difference in building revolutionary power, trying to build a clandestine armed movement. You’re building a different kind of revolutionary when you fund yourself through armed actions that target financial institutions to uphold capitalism as opposed to having Uncle John send you $10,000 stipend every month. And you can extrapolate from that into the nonprofit industrial complex. I know some really good people and good organizations that are nonprofits and they skimp to get by to do some really good community work. But there are a lot of nonprofits where the money just rolls in regularly every month, some grant, some foundation, to pay your pretty decent salary and all the benefits that are accrued with it…it makes for a different organization. It makes for a different mindset. Anyways, where were we?

UoF: Not to oversimplify, but I think you could say that guerrillas inside of the imperial core take two distinct paths — one, those who think revolution is impossible within the core, and their primary goal is to give as much material support to Third World revolutionaries, without the expectation that the masses here will join them. And two, those who may share the primary goal of materially supporting Third World revolutionaries, but also think revolution is possible within the core and aim to win popular support and grow their ranks. Of course there has been a lot of internal disagreement on these questions within some of the formations we’re talking about. And in the so-called United States it’s more complex than, say, Denmark, because it’s built on settler colonialism. The “working class” here is still largely pacified by imperial super profits but there are also internal colonies with far more revolutionary potential because they are fighting national liberation struggles. How did you all conceptualize revolution here, and how did the UFF relate to the Third World national liberation struggles, including those internal to the US?

RLL: Well, when I was part of it, we were trying to build a revolutionary resistance movement. We were anti-imperialists. So much is based on time, place, and conditions. If you don’t factor in time, place, and conditions into things, you can get off the mark really well, including with armed actions and stuff. You’ve got to factor these three components in to make decisions about how you’re going to move. At that time we’re talking, if you go back to SM-JJ [Sam Melville-Jonathan Jackson Unit], you’re talking early, mid-seventies, and then all the way up to UFF [United Freedom Front].

The last UFF action was 1984. It’s an interesting communiqué that UFF put out. They hit Union Carbide, which was a big mining company in South Africa, Amerikan-owned multinational, and the communiqué answer the call to all parts of the anti-apartheid movement that existed at that time and any progressive revolutionary people that. It was really coming together pretty well, this aboveground anti-apartheid movement in the US at the time. But this communiqué was encouraging that [aboveground] movement to continue, while recognizing that we’re trying to build a multifaceted anti-imperialist movement, which for us necessitated a clandestine sector that was armed, armed for self-defense, and armed for offensive actions and that they were not mutually exclusive, that they should compliment each other. Multilevel, we’re at different levels, but we’re part of the same movement. So we encouraged the BDS movement at the time, students, workers, etc, to keep at it the same way because we were going to keep it at it as well.

In terms of that anti-imperialist view from going back to the seventies into the eighties, we clearly really took our view of things based a lot on the national liberation struggles of the time. When you go back then, they were all over the world, anti-colonial struggles included in that. Just look at Africa: Mozambique, South Africa, Namibia, Angola. To us, these Third World national liberation struggles were a cutting edge of resisting and fighting back against US imperialism as it spread throughout the world. Each one of those countries that liberated itself was going to weaken US imperialism to some degree. And our role in part was to be supportive of those struggles. International solidarity, if you need a term for it. That was how we considered ourselves; they’re the vanguard, we’re the rear guard. The rear guard because we’re in the Belly of the Beast, we’re the US, we have some responsibility politically, morally, personally to do something, to attack the same system that’s being attacked by these revolutionary movements. It’s a unique position to be within the US and try to fight on the same field of battle, so to speak, in support of these liberation struggles.

The great thinkers and guerrilla fighters that came out of these struggles [in the Third World] had a lot of influence on our own political vision and analysis. I was looking at the reading list on the Unity of Fields website. I can tell you, I’ve read many of those books. Everything from Carlos Marighella, Minimanual of the Urban Guerrilla. These were tremendously influential on us because Urban Guerrilla Warfare was relatively new at that time. It was like opening up a new area. George Jackson says, I think in Blood in my Eye, that the urban landscape can conceal a guerrilla as well as the jungle canopy. And we took that to heart.

What came after liberation in each of those countries, you know, we paid a lot of attention to the groups made up the different movements in the different colonies and different countries, because sometimes there would be multiple organizations. Obviously we would favor the political view of one group usually, but it wasn’t our job to put that out there. That was just to enable us to see what direction things were going in, and which organizations in these movements had the best prospects of really freeing the people there. So what came after liberation, we didn’t delve into, other than you’re freeing up a colony, you’re freeing up a people, which means self-determination for the first time for these people so that they are in a position, once they liberate themselves from foreign conflict, colonization or intervention, then they are much better suited to determine by themselves the direction they want to take to put that liberation into real terms for their people. Our actions were meant to keep those liberation struggles on the agenda in this country, both with the left and as much of the general public as we could reach through what we were doing.

I think you mentioned the internal colonies as well, and that somewhat unique situation. Not all the underground groups from that period looked at internal colonies the same way. Even within certain organizations, it generally might not be completely unified on a position on the internal colonies. Our position was that Black people in this country do compromise an internal colony. So we’re looking at Black people, what do they want? What are the Black radical groups saying? What are they doing? Recognizing that somebody’s internally colonized is different than offering a format to deal with that. So it wasn’t our position to offer that format, our position was to support a freedom struggle. If you look at the position papers and communiqués and underground papers from that era, you’ll see that there is support for the national liberation of all of those internal colonies.

We did get very involved with the Puerto Rican struggle, which is a little bit different in the sense that you have the diaspora here, you have a huge number of Puerto Ricans in this country, but the island is the land base of the nation. How they were going to deal with the diaspora, that comes with liberating your national borders. That’s the way I see it, anyways. We were really supportive of Puerto Rican independence and the release of the Puerto Rican nationalist prisoners that were kept at that time, Lolita LeBron and the others, and in fact, we were charged with quite a few actions around Puerto Rican independence. That we felt was very material support given as many Puerto Ricans in this country. My number one goal has been dismantle this fucking imperialist system. I think the internal colonies are a potential Achilles heel of imperialism right within its own borders.

UoF: Absolutely agree. I was going to ask you a question about the state of the Palestine solidarity movement in this country, and I think that’s actually very related to our discussion about the internal colonies. Because the most useful thing we could do here for Palestine, for any Third World national liberation struggle, is to make a revolution here — to dismantle US imperialism from within. And obviously the internal colonies, now and historically, have the most revolutionary potential, so that goes hand in hand.

I think the “Palestine solidarity movement,” as they call it, is coming up against the limitations of its own form. I’m not trying to say this in a defeatist way because I also think the movement has made great advances, but those advances have led us to this impasse or breaking point. The movement has failed in part by not addressing this issue of internal colonialism, by not universalizing the Palestinian struggle into a broader anti-imperialist struggle. That failure has manifested itself most clearly in the movement’s weak positions on the police, on resistance to the police, and on whether militancy should take place here at all. There’s a lot of rhetorical support for resistance far away, but not when it takes place here, which is why the movement also ignores a lot of the political prisoners in Amerikan dungeons, like Casey Goonan. And to be clear, when I say “movement,” I’m mostly talking about the nonprofit industrial complex, which is why I don’t even like using the term “movement” really, and I appreciated your critique of nonprofits earlier and how reformist they tend to become. But back to my point — we’ll be chanting “resistance is justified when people are occupied” at police-permitted and peace-police-marshalled parades without acknowledging that the Amerikan police are the domestic occupying force of the internal colonies here. That idea leads us to the logical conclusiont hat we should be resisting the police, and I don’t think these nonprofits actually really want people to do that, because like you said, they care about their grant money and their bottomline.

When we were chatting the other week, you were also comparing how you and your comrades would be policed for supporting the Vietnamese National Liberation Front (NLF) and waving their flags at protests to how we are now told not to wave our Hezbollah flags or wear Hamas or PFLP headbands. So this kind of conditional “solidarity” that is actually anti-resistance is definitely not a new phenomenon, although the existence of the terror lists and designations has made people all the more scared of resistance, or given them more excuses to shy away from openly supporting it.

But yeah, I guess I’m wondering what you think of the Palestine solidarity movement now, especially in this current wave of repression. Do you think the movement can transcend the limits of its current framework, its single issueism, really break out into a broader anti-imperialist movement?

RLL: Important question. Well, the Palestine solidarity movement, I mean, I’m not the best judge of this in my current situation. You could be a better judge of it than me. I don’t know.

I used to get into it with activists from New York a lot because I detected this attitude among some that New York was the center of the universe, and what people do outside of the center of that universe somehow doesn’t quite measure up to what’s up in New York. And it’s not just with somebody like me who lives in rural Maine, but I got friends and comrades in Boston and they get to sometimes the same way that they feel like, especially when they’re working with people and they want to put an event together. “Oh, is this is going to be New York or Boston,” and Boston seems to play in second field all the time and it sort irritates them. Or you get over into the Bay Area, it is very different being a radical in a place like rural Maine. I think I could mesh in much easier in the city like New York or the Bay Area that has a lot of old radicals, but in a place like Maine, it’s like you’re the only game in town. That’s why its fricking media and the cops still know who I am despite the time that’s gone by.

But anyways, first of all, I’m going to say this question has come up even here in Maine, and we have some very committed activists here to figuring out which way forward, examining and reexamining actions that people are involved with. Everything from cultural events to CD [civil disobedience] where people get arrested and all these marches and all these rallies. I saw the piece on PSL in Unity of Fields and apparently there’s some differences there over strategy. I mean, PSL is here. I know some of them, I knew ’em before they were PSL. PSL hasn’t been around in any significant numbers until relatively recently. I mean it predates October 2023, but they hadn’t been around and they’re recruiting. When it comes to which way forward with Palestine solidarity, it’s still a work in progress as various groups hold a range of strategies and tactics. It’s an issue here in Maine and people talk about it because they want to build on what’s happened so far.

The positive thing that I see is that I have never seen so much support, I’ll use it generically, the word “support,” and awareness around the Palestinian liberation struggle as I see now. That’s happened since October of 2023. I’ve seen it manifested in many different ways and I’ve also seen it in other parts of the country. I’m in touch with activists in other parts of the country. I’m seeing the same thing there. I could take it a step further and see it also in significant parts of the world.

Because historically among the left, and I’m not talking about different party lines between different sectarian groups who want to argue to death over some line, I’m talking about substantive issues — you couldn’t find a lefty group in this country that wasn’t opposed to apartheid South Africa. But as the years passed by, Palestine was always, and forgive me if I’m repeating myself, but to put it in New York terms, Palestine was always considered the third rail of left politics.

You know, the third rail in the subway, you touch a third rail and you’re instantly fried, you die. Periodically somebody does that in the subway system and that’s what happens to them. I personally know somebody who happened to die that way. In the NYPD investigation of how he died, they said he tripped and fell on it. This was a young anarchist kid that I knew. This is quite a few years ago. While his comrade was saying no, he got jumped and pushed on it. But in any event, you touch it, you die.

So if you were a supporter of Palestine, you risked being ostracized by people, either individually within a group or by another group. It was always like you could give Palestine a certain amount of rhetorical support in your publication or whatever, but don’t get too heavy-handed with it. Don’t push the resistance too much and don’t push the one [Palestinian] state too much and those kind of things. If you did, then you risk being ostracized politically by other leftists.

I’ve seen that starting to go by the wayside for the first time in my life. I’ve never seen this level of support before. I understand we’d have to go qualify it by going through what do I mean by support? You know what I mean? This and this. But I mean you take ten different ways that people can be supportive from financial to cultural to CD [civil disobedience] to every kind of thing in between, then I think there’s a big positive. It’s a positive, it can be built on, people are trying to build on it, it could grow even more.

I mean, we don’t know what’s going on in Palestine until next week gets here. So much is up in the air right now. None of it seems good, but I think that’s been a pretty amazing thing. You could say, yeah, well, a lot of these people are basic liberals and maybe their idea of Palestine solidarity is to keep writing to their Congress person to vote to stop arms to israel or write a letter to the editor or whatever. I don’t discourage any of that kind of stuff. I just push people to do more. Or I don’t push, I used to push. I try to persuade people to do more. So I think that’s really good.

I think part of the reason you’re seeing the repression amped up, it’s not just because Trump is here, it’s because they’re worried about that level of support [for Palestine] and that’s why they’re coming after people to the extent that they are. I don’t think it’s going to stay this way, I think it’s going to get worse, but I still think that they are predominantly focused on low-hanging fruit. I hate to use that term, but I’ll use it. I’m accustomed to this because I was a prisoner for a long time and I see them do a lot of things to prisoners that people out here just don’t care about, don’t know about, don’t want to know about, and it’s out of sight, out of mind, it’s prisoners, the lower end of everybody. And then five years later they’re doing the same thing to people outside of prison. I can talk about surveillance technologies and all kinds of stuff. They’ll experiment with the prisons first. That’s the low-hanging fruit because we’re the most vulnerable, we’re the most marginalized.

What they’re doing now, especially with the deportation stuff, is they’re targeting people. Totally make up a fucking story. But they’re going after people they know are vulnerable because they’re not a US citizen yet, or they can manipulate a law even if they got a green card or whatever to deport them. Something like this happened with the Red Scare with Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman and various anarchists and communists that were put on boats, just rounded up and put on boats, and sent to other countries. I think that’s part of the reason why we’re seeing this repression, and it’s a great cause for concern because of the level of fear it induces and also because we have to come to the defense of these people that are being subjected to this repression.

It’s a moral and political obligation that we do that. But it also requires resources. It also requires our attention, our time, our money, whatever support we can muster to defend people that are going to being targeted by this repression. That’s not to say that we should do any less, we should do more to defend people that are under attack. If you follow Cop City at all, you know what I’m talking about. All these people that are being deported could eventually prevail in their case, but the government still has succeeded in disrupting movement activities, scaring people that may be involved away. To them, they look at it like a win-win situation. If they can deport somebody and keep them out, that’s a win. But even if that person comes back, they figure they’d want something because he may be back, but they scared 20 people away, or they tied up people in organizations, tied those resources up, so they can’t be used for anything else.

So I think that the potential is still there right now, despite the repression. I talked about time, place, and conditions — we didn’t have this internet before, we have to get on the fucking internet on a daily basis to find out how those conditions are changing. If you don’t have a good grasp of conditions, then it’s difficult to put together tactical and strategic plans of any kind. And it changes so much. But I think the potential is still there. This movement can grow now.

Single-issue? Yeah, I mean I have to think of the Vietnam War because there were so many people. I was a state coordinator of Vietnam Veterans Against the War, and my Vietnam veteran partner in that had been a highly decorated army helicopter pilot. I was already an anti-imperialist by the time I got involved with VVAW. And this brother, he was strictly a single-issue person. He wanted to bring this war to an end and it had a moral base to it to a certain degree. He had studied to be a Jesuit before he got hooked into the military and he had strong moral objections to the US being in Vietnam and what they were doing there. I mean combined together, we made some really formidable presentations and worked all well together. But the minute that all was done, that was it. That was the end of his political activism. I immediately jumped. I didn’t wait until the war to be completely over, but it was obviously going to be. I already had made my way into working around the criminal legal system, prisoners and all of that. This was in the seventies when the prisoners rights thing was really big. That turned out to be a good move politically because I never looked at the war as a single issue. To me it was always connected. I just looked at my fucking training, and when I was in Vietnam, to know that white supremacy ran through the whole fricking war. It was white supremacy, racism on a massive scale. It was embedded into us in our training before we even got there. But yeah, I think that that is a problem probably, well, it depends how you look at it, whether it’s a problem or not. It’s a problem in terms of building an anti-imperialist movement. It’s probably a problem for these sectarian groups, including groups like PSL that obviously are involved in more than one issue. When you bring somebody into your organization or group or whatever, this is where political education comes in, really. You got to have political education I feel.

A lot of people could be resistant to that, but I think that’s a good method in which to solidify people’s views about the system and making the connections. Most of the public speaking I do, I just did a class yesterday, it’s focused on prisons and I work in other stuff. I can’t when it’s an academic presentation, which it was, I got an hour and a quarter, and so I can’t go too far afield or I’m not meeting the qualifications of that particular class. I have to keep the focus on this issue, connecting it to larger issues in the criminal legal system, but also connecting it to the issue that are political prisoners in the US, because I always give a very quick thumbnail sketch of my background, my backstory as I call it. I open up, I didn’t just get here yesterday, you know what I mean? I was just a kid from a mill town and this war is originally what turned me on, then being in prison a year after I got out of the army, those dots were connected for me. So they see that right away that I have a more expansive view than just prison. But yeah, I don’t know how big an issue it needs to be right now. How many of these people are going to bail out on Palestine when we get to wherever we’re getting to?

I mean, I’m dealing with some people like that here. The best thing I’ve seen happen is that so many generic anti-war people are doing vigils and stuff. I first ran into them when I got out in 2004 because we were doing them around Iraq, then it was Afghanistan, and they’re against the armaments industry, but they can be pretty generic about it, with their signs and their talk. But I’ve seen some of them cross over into the Palestine issue, which is a big step for some of them. They tend to be politically, how should I put this? Politically, they emphasize nonviolence rather than liberation. I’m going to put it that way. If you’re an anti-imperialist, you emphasize liberation. And resistance to imperialism can be violent or it can be nonviolent. It can be both. But I don’t make a fetish out of nonviolence either philosophically or as a practical manner. Some of these people are crossing over, which is encouraging.

I’m not sure if I’m getting to the issue. We started talking about the demonstration [I went to in Maine recently]. People were showing up from different organizations with all kinds of different issues. I didn’t have any problem with people talking about losing their jobs and social security and healthcare, not war. I understand those issues, but I think the challenge in terms of recruiting people or encouraging people to get involved in Palestine solidarity is you have to be able to show them how it’s related, why Palestine is related to George Floyd, you know what I mean?

UoF: A connection Yahya Sinwar made himself, in one of his last interviews with Western press before the Al-Aqsa Flood. He said in 2021, “The same type of racism that killed George Floyd is being used (by the zionist entity) against the Palestinians.”

RLL: Yeah, you have to do that. I’ve been doing it in one form or another, going back to when I first became politically active. I became active on three fronts — the Vietnam War, the labor struggle, and civil rights. And so that shows right away that as soon as I got politically active in 1968, after I got out of the army, I was connecting the issues right away. So was the organization I was part of, Southern Student Organizing Committee, which sometimes is called a Southern SDS, but I don’t think that’s a really good description. And so our pamphlets and everything reflected that. We had pamphlets by Che Guevara, the Tricontinental Speech, Malcolm X, the history of IWW, whatever that general political education that these issues are related. And I think that long-term, wherever this direction goes with Palestine, is going to be a necessity for solidarity work with Palestine, for a Palestine. It’s going to continue for a long time. You learn from experience and I’ve been around quite a few people who are pretty capable and you can chew gum and walk at the same time other you can do be involved with some other kind of issue as well. We shouldn’t be in a competition to, well, if you’re with this group, you can’t do this over here. If you’re with us, you can’t do that over there. I don’t want to get into too much of that.

UoF: Yeah, totally. We do need unity. And when we say that we mean unity in resistance, not just unity for unity’s sake, which I feel like is what you’re getting to. Everything you’ve said is really reaffirming why we thought it was so important to do this interview because with all this new repression coming down, we certainly are in a new stage, but we’re seeing some people talk about it as if it’s unprecedented when it’s very, very precedented. Maybe people are saying this because because we don’t know our own history, so these historical examples of repression and counter-repression are crucial to study. Our lives depend on it. And we’re really grateful you’re sharing all your experiences. Getting back to the UFF, we were talking about how yall managed to evade capture and stay underground for so long. As our movement is experiencing more surveillance and infiltration, I think this could be really useful advice to people engaged in all sorts of different tactics, so I was wondering if you could speak to how yall vetted people and dealt with infiltration or traitorship.

RLL: That’s been the bane of a number of organizations. The worst snitches are not the ones that you manage to identify or that prove themselves unworthy after they’ve become involved in some kind of one form or another with clandestine work. [The worst snitches are] the people who break after the shit goes down. In other words, a person could be underground for three years, have participated in all kinds of stuff, been dependable, get busted, and they’ll sit him in a fucking room, slap him a couple of times, and they start talking and they’re going to slap him again to shut him up. In other words, they’re passed certain tests and are vetted, so to speak, through actually doing things, but when the heat dial hits a certain level, especially if you are arrested or captured and all of a sudden you are looking at enormous amount of time—just to give you one example, in a very bad prison, that kind of thing—and somebody completely falls apart.

That’s a critical question because you’re talking about trust. The deeper in you are, and I don’t mean just underground, there’s a lot of people that get indicted or dragged before grand juries that are aboveground people, some who violate the law and some who don’t. They love fucking conspiracy laws in this country because they’re easy to convict people on. So why do people use Signal? Presumably to give them some kind of protection against conspiracy charges, right? I mean, I won’t get into that. I’ve been charged with conspiracy, different kinds of conspiracies and I know how the law works and that’s a favorite tactic.

In terms of clandestinity, you’re talking about much higher risk and much more serious consequences generally speaking in that kind of situation. So a vetting process procedure is more serious. The gate somebody has to go through to assume a role underground should be fairly vigorous. And this is an issue I touch on in my book because it is so important and there’s no one size that fits all. There’s no particular test that will guarantee you that you are protected against somebody. I mean, there’s various kinds of informants and agents, provocateur or whatnot. If you go back and you look at these groups, a lot of them did have snitches rise out of ’em. In a way, the ones I feel that hurt the most, I mean if somebody comes in, they’re an undercover agent and you get set up and you get busted, that sucks, that hurts, but that’s not going to hurt the way your closest friend in your whole life flips and testifies against you. That really hurts. Or to set you up in a way where one of your comrades get killed or injured or busted, ends up in a fourty-year sentence, whatever. And that kind of betrayal is very difficult to flesh it out because it really comes down to an issue primarily of character. You have to assess a person’s character and you don’t know what somebody’s going to be like for sure until they’ve passed a trial under fire. I’ve known soldiers, conventional soldiers in the United States Army that got grade A’s all through basic and advanced training to be a soldier, fundamental part of learning how to kill somebody. But then when they come under actual enemy fire, they fall completely to pieces, where another trainee soldier who just kind of grunted and just kept their head down and nobody noticed him and he just got through basic training, advanced training and nothing special, nothing else stands out about him, but under fire after training in the real war, they rise above the others. They are able to do everything that a good soldier is supposed to do in a war situation under fire.

So it’s really hard. That comes down to a character issue. And a lot of those other groups got burned. They got burned both ways. They got burned because they recruited the wrong people who turned out pretty quickly to be weak, undependable. They were alright until some cop starts twisting their arm and puts them on a hot seat and they break down and give up information, give up people. Part of it is like being spoken for, recruiting people that others can vouch for. That’s an important thing. Assuming the people that are vouching for them have proven their own selves in one way or another and a trusted comrade, that’s the best referral you can get unless you are coming into the group somebody grew up with or something they’ve known forever or whatever. Because trust is the basic thing. Nobody in our cases ever flipped and they had a lot of pressure. A lot of pressure, because we had kids involved too. And then you got both parents looking at a huge amount of pressures and years to flip and turn government witness. We didn’t have any. Our policy was “Give us 24 hours.” Meaning that we understand that every human is likely to have a breaking point when it comes to brutality and torture. So, a captive holding out for at least 24 hours or longer gives others a chance to dump anything that could be compromised and move on to safety. I think it important to include this because it’s part of the security code but also shows we are not insensitive to those who suffer severe consequences because of their commitment.

We had a snitch. We had people, aboveground support people, who basically testified for grand juries. That’s a whole other issue, but it’s related to this. We used to see a lot of use by the government of grand juries to particularly go after aboveground people seeking information on both the aboveground support networks for the clandestine and for anything they knew about people underground themselves.

But we had one person who flipped early on, and I write about this in my book because this person came to us recommended, but he should have never been recruited. At some point I was starting to notice this person’s character was weak. A number of things happened that told me this person is weak. He was too mouthy, too pushy about we got to do this, we got to do this, we got to do this. You know what I mean? When we didn’t have the capacity to do it, he’s trying to push us into doing actions that at the time would’ve been over our head. So I talked to another comrade about it. He was feeling the same way, this is when it can get dangerous. You’re talking about an armed clandestine movement here, armed organizations, different ways to deal with different disciplinary issues underground. And you got to be very careful and conscientious about how you do it.

There was another unit operating in the same general area as we were. We had a liaison between them and I was really getting uncomfortable with this guy. The other unit expressed interest in him. The guy that I’m talking about, the recruit, the person of bad character, I feel, I told the liaison take him if you want him, but I told the other group, through the liaison, I got questions about this guy’s character. I don’t know, if he’ll hold up, you should know that. The other person in the other group, they wanted him. So we dumped him and the minute he made that change over, we abandoned the safe house. He knew this one safe house where several of us lived and I was so concerned about him that we decided to dump that house, because that was the one place he knew. So if he did collaborate, that’s all he could lead them to and we’d be gone. So he fell in with this other group and I was clear to the other group, we don’t want anything more to do with him. We could have taken more drastic action, but that’s a whole other issue that I don’t want to get into for this. This guy was like all he wanted do was actions, get out there, get out there, boom, hit him again, boom, hit them again. This other group was into that kind of philosophy. I knew there was going to be a problem there. So we cut the liason off and sure enough they got down in the city and they just went to town and they went way beyond that capacity. They were going big there for a few weeks, but it all came crashing down.

This guy I was telling you about was busted with some of the others and part of a aboveground support network. They got into the police barracks, scared him, and the guy never stopped talking. I got his completely grand jury testimony. He buried that whole other group. They all went to prison and broke it up as an organization. At least one person in the aboveground group went to prison. And sure enough, they found that safe house, which we had up on the Canadian border and they went in it. But by the time that happened, we had been gone two or three months by then. He completely turned weak, sold everybody out, and then started lying so that he could incriminate more people and try to incriminate me. He starts lying.

But the underlying factor in all this is desperation. If you can’t recruit when you’re underground or doing any other sensitive stuff — unless your philosophy is we’re going to have a group of two or three people, that’s it, that’s going to be enough to do what we want do the way we want to do it, we don’t need anything more than that — but if you’re trying to build a movement, you need something larger than that. That means you need recruits. And we were desperate for a recruit at the time. He first came in with us, referred to by somebody who’s judgment I trusted, and he was a trustworthy person, he never snitched or anything like that, but his judgment wasn’t the greatest. So when you recruit from a position of desperation, then you’re going to make mistakes. You’re going to lower the bar when you evaluate a person. Can this person hold up to this kind of way of living underground, to do the kind of things that is going to be required of that person to do? The minute you start lowering the bar, the risk is greater that you’re going to pull somebody in that’s going to burn you somewhere down the line.

The same thing with an action. Let’s say an expropriation. The worst time to do an expropriation is when you are desperate. You don’t even have next month’s rent. And that’s all tied into your security. If you can’t pay the rent and you get thrown out, you can’t be out on the street. You’re desperate. So you try to avoid that situation. You have enough of a bankroll from expropriations that you are not that desperate to go out and do that again. You’ve got to do it at a time when you have the resources to do it right. It’s the same thing with recruiting people. Don’t let yourself get so politically desperate to have this person or two more people into a group that you’re going to lower the standards, lower the bar in terms of what you’ve determined it takes from your own experience to do the work that would be required of this person.

Fortunately there was nobody else after him with us that did that. When we recruited again later, we had had a lot of experience by then and we needed other people, but we didn’t get to the point where we were desperate. We needed it but we had years of experience — we knew pretty much the requirements of a person to live underground with a lot of heat on you and to do the kinds of things that are necessary. A lot of that stuff is stuff that even aboveground activists don’t know because they haven’t been through the experience — how many ways you can make yourself look and sound different, everything you need to know about fictitious identification and on and on, right down to the littlest details. We had documents, you’ll find some of this in my archives at UMass, they were like little training manuals for new recruits. So the people were given some orientation period to what would be required of them because people don’t have much experience with underground. And the lack of experience has cost people their lives underground.

UoF: That was so useful, I think to a lot of people reading this who are doing all different kinds of work. The points you make about how being aboveground or being a public-facing spokesperson does not mean you are safe is really important. A lot of the people we’re seeing get abducted right now were those public facing people and were in fact sometimes very moderate politically and they’re still being targeted. It’s not just people doing direct action that need to be preparing for grand jury resistance, etc, that sort of repression will target our movement at every level.

I wanted to close out maybe by asking you about why the UFF was originally named the Sam Melville-Jonathan Jackson Unit, if you could speak to the significance of these two freedom fighters. I know you just read the interview we did with Jonathan Peter Jackson Jr.

RLL: Well, Jonathan Jackson was really very influential on me, even before I went underground. Not only with me, but with others, especially those of us who were underground, to the point where Tom Manning and Carol Manning who were part of our group named their son who was born underground after him. His son was born underground. Thinking about kids, it’s a whole other subject, right? One thing I learned underground was, and I learned it from my partner, this is the kind of thing that a normal aboveground person would not think of, that a very pregnant woman can move better underground and faster than a woman with a two or three-weeks-old child. And we actually learned that from experience.

Now, who contemplating going underground is thinking about something like that? I mean, this goes back to what I was saying, before we get off into a hundred things about living that life. But Jonathan was the inspiration, as I told you about, for our coded secret dating system. It was based on a calendar that was, and you can see, George’s words in the back of his last page of his book, in Soledad Brother, that the death of Jonathan was such an important event it need to be noted on our calendars, ad infinitum, in other words, forever. So we developed a calendar based on that, that began with the first day after Jonathan’s death.*

Jonathan, as a 17-year-old manchild coming from a colonized nation, an internal colony, he really represented and signified and epitomized Carlos Marighella’s words, that “The duty of the revolutionary is to make the revolution.” Without initiative there is no action. Jonathan, he has the kind of heart that it takes to be a revolutionary it takes to sacrifice and live that commitment and to the fullest. He was a 17-year-old version of Carlos Margighella, really, in a way.

I remember an interview with Jonathan Jackson from a very long time ago. I don’t remember the publication, but this was when he was working on the Soledad Brothers’ case, and I remember him being asked why he was so angry, and why he was so militant, something to that effect. And his answer was, “What would you do if it was your brother?” That resonated with me, and I felt that deeply, and I still do. Because to make the kind of sacrifice that he made, to make that commitment and then that sacrifice, to put it all on the line, to rescue those brothers, to free those brothers from the Marin County Courthouse, that’s as much heart as you can bring into anything. And if you had a hundred like him, you could probably take some very significant steps and forward movement to bringing this whole fucking system down.

That’s the kind of heart it takes. That’s a warrior’s heart, and there’s different ways to express it. But the thing that he said, when he said “What if it was your brother,” he’s trying to get people that don’t quite wrap their head around liberating Black captives using firearms. They can’t quite wrap their head around it. So he phrased it that way. To him, it could be his brother George, or it could have been William Christmas or Ruchell Magee because they were there too. But that’s the essential core of a revolutionary, is to identify really strongly, emotionally with oppressed people.

In the cases that I was involved with around, let’s say, the slaughter that was going on in Central America in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Nicaragua at the time — I’m going to telling the jury this. I represent myself. I can give my own statements. I don’t identify with the ruling class in this country, the Ronald Reagans and the elites of either party, the fucking collaborators, whether the head of unions or head of associations or whatever they were the head. Who I identified with were the campesinos that were struggling and fighting for the own liberation in Central America, be they Mayans in Guatemala or the Sandinistas in Nicaragua. You have to have that feeling, and it’s part of what enabled me to do what I did blissfully and wish I could do more, because that’s what my love was, that’s what my feeling was for these people. And Jonathan was like that. I mean, he was like a hero, that’s an overused word these days, but he really was, a great inspiration to us.

UoF: It reminds me of what George said about martyrdom, that we shouldn’t cry, we should celebrate, we should only be sad that it’s taken so long for people willing to make those sacrifices to arrive. “These comrades must make the first contribution. They will be the first to fall. We gather up their bodies, clean them, kiss them and smile. Their funerals should be gala affairs, of home-brewed wine and revolutionary music to do the dance of death by. We should be sad only that it’s taken us so many generations to produce them.”

RLL: Yeah. I’ve ran into this because I’ve done so much work around political prisoners, and it’s an abstract thing to a lot of people, and I always use the term our political prisoners, because to really be inspired enough to do any solidarity support work around political prisoners in this country, especially if you haven’t done any, you’ve got to take that first step to understand why you need to support activists when they’re imprisoned, and you look at other countries, just look at Palestine, you get a good example. They embrace their imprisoned people. They don’t marginalize them. So I always tell people, these are our political prisoners. It doesn’t mean you have to agree with every fricking thing that they did tactically or strategically or anything else. I mean, if somebody goes to prison for sabotaging the Dakota Pipeline, I may not have the same politics as them, but I totally understand what’s going on here and whose side I’m on, and then that person needs support. So I say, these are our prisoners. This is how you have to think about it. These are our prisoners.

So when I used to look at what was happening in Central America, I’m not looking at like, oh, these foreigners down here. These are people that our struggle is meant to provide some kind of support for, to expose the truth of what’s happening to them, to expose the government’s criminal enterprise and criminal activity that’s destroying these people, taking their lives from them. You have to have that sort of heart to heart connection. It has to beyond abstract. It doesn’t mean that you have to have a gun in your hand as Jonathan did on that particular day, but it means that to be able to step up, do more work, make more sacrifices of your time, your resources — whatever you need to see people like that.

I was doing stuff that I had never done before. The battlefield had completely changed. To me, once you get ensnared into that criminal legal system and you’re looking at trials and stuff, to me, it’s an extension of the battlefield you just left. And the battlefield I just left, the underground, the odds were always against us. We were always outgunned, outnumbered, outresourced. It was the David versus Goliath kind of situation. I get into captivity and I realize this is an extension of that same battlefield. I’m outgunned, outnumbered, out, resourced. They’re trying to like hell to destroy me and my comrades. And so the tactics have to change, the strategy has to change, but it’s the same struggle, just on a different plane. And then when you get to prison, same thing there, it changes again and the odds to increase against you again, and you have to make it work there.

And in prison, it always goes back to the same thing we thought about earlier, political education. I never knew a political prisoner in prison doing any kind of years that didn’t engage in political education and tried to get little groups going or exchanges, depending on the situation you were in, with people who were there for offenses that were not political, but to try to change their consciousness, especially with the youngsters.

Of course, George is very big on this in his book. I mean, he really goes on about the importance of political education in that situation. Sam Melville was also an influence on me. I did not know Sam Melville personally, but my admiration for him stems as much, if not more, from his role in Attica than his relatively brief underground years. Although I have to admire anybody that bombed United Fruit, which he did, it goes by a different name now. But I mean, when you look at what has been designated as a genocide directed to Mayan people by the US-backed regime in Guatemala in the eighties, I mean, that’s where United Fruit was from. They owned fucking Guatemala. And so I was pleased to see that. If you’re reading Sam’s history, you realize he made some mistakes as he wasn’t real well acquainted with living and operating underground, and he stood up through all of it. I think it comes down, and this applies to Jonathan too, but Sam Melville, despite whatever personal deficiencies he had, he was a person of principle.

I can tell you from my own experience, and when I was going into the last part of the last year that I was underground, the tenth year, the writing sort of was on the wall. Most of the underground groups that were operating on any level at all when we first went underground were decommissioned. People were in prison, some died, some just scattered. The network of groups that existed was down to very little in 1984. In fact, it only continued on into ’85 and not really beyond that.

Part of the hopes of building something, I’m looking at it in 1984, and the people that I thought would still be there were gone, and they hadn’t been replaced. I knew then that our hopes of really setting up a network of clandestine groups, anti-imperialist clandestine groups that could go even much farther than 10 years, was almost a pipe dream at that point. But I kept going because of principle. Apartheid still existed in South Africa, and the slaughters going on in Central America were still happening. I would justify it to myself personally, I felt that as a matter of principle, I was not going to give up the struggle at that point. I was going to keep going, even if it was only based on a matter of principle, even if the material conditions were just absolutely not there anymore, beyond just basic survival to build anything more, I was still going to keep going, at least for the immediate future, which of course ended on November 4th, 1984.

UoF: We ended the interview here. *Ray emailed us this note after:

FYI: On the last letter, last page of Soledad Brother George writes:

August 9, 1970 Real Date, 2 days A.D.

Dear Joan, We reckon all time in the future from the day of the man-child’s death.

We devised a dating system based on this which took an FBI counter-terrorism resource center months to figure out, simple as it is.

In our NY trial the prosecutor presenting their closing statement to the jury brought up that 2 of our comrades/defendants had the audacity to name their son after Jonathan Jackson who kidnapped a judge, etc, etc. His point being that these people are radical extremists who not only engage in political violence, they celebrate it.

Download a zine version to print/fold here: