China’s rise is reshaping the world. US hegemony is crumbling, and a “Chinese century” is no longer unthinkable. From socialist book clubs to US anti-communist think tanks, people rush to explain what China is and how it came to be.

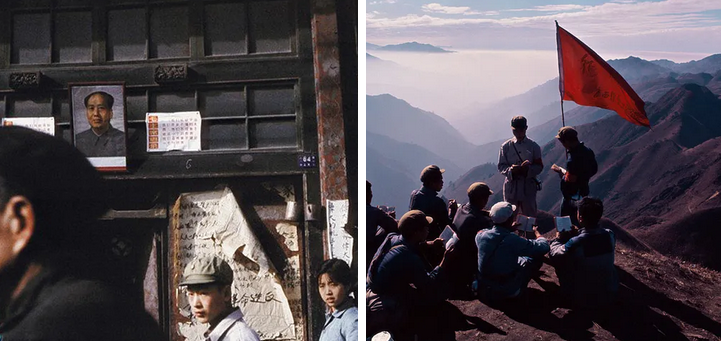

Yet to understand China today, it is not enough to analyze GDP figures or geopolitics. You have to understand how the People’s Republic was forged, and above all, the upheaval that marked its most contested and transformative moment: the Cultural Revolution. To explore this history from the inside, [comra] sat down with Red Guard veteran Fred Engst in Beijing.

“[…] the Cultural Revolution was the most comprehensive, the longest-lasting, the most thoroughgoing, and the most in-depth experiment of the working class to explore how to be the real master of society,” Engst said.

Known in China as Yang Heping, Engst was born in Beijing to American communist parents who joined the Chinese revolution in the 1940s. Raised on a state farm in the Chinese countryside, a Red Guard in his teens, a factory worker on both sides of the Pacific, and later an economist, Engst lived the Cultural Revolution before spending decades trying to understand it.

In the first part of this two-part interview, he reflects on his personal experiences, the lessons of that turbulent era, and why one of the most misunderstood periods of modern Chinese history still matters today.

[comra]: You grew up during revolutionary China’s most formative years. There are many misconceptions surrounding that era; what was it actually like to experience it firsthand?

Fred Engst: Well, it’s hard to ask fish to describe water, isn’t it? What I can say, of course, is in contrast to other experiences. What made China a revolutionary society was not that it kept on talking about the glorious past, but rather that it had to deal with the contemporary issues [it was facing]. And the Cultural Revolution was a case in point. That was really inspiring when I was in seventh grade […]

Young people generally tend to be rebellious, right? You know, middle school and high school kids are in their rebellious age. So they’ve been very easily drawn to this idea that we should not just learn through books. The reason we learn stuff in school is to become the rulers in society. Because the traditional Chinese idea is that rulers use their brains, and the people use their muscles. That’s the Confucian idea. We were rebelling against that kind of Confucian idea. Unfortunately, today, that’s the dominant idea.

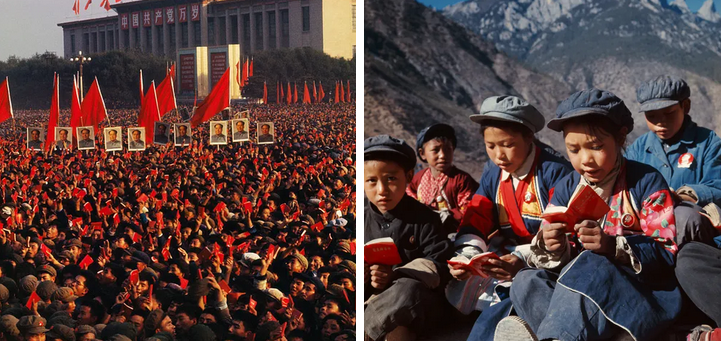

What is socialism? How to achieve socialism? Is a peaceful transition from capitalism to socialism possible? And when you have socialism, how do you know you have socialism? These were the kind of debates that really excited the youth. And they wanted to make sure that China stayed on the socialist road rather than learning from capitalist society. That was the spirit of the students. And of course, that eventually led them to the workers and peasants. Once the working class overthrows capitalism, feudalism, and imperialism and sets up a new government, then the real issue becomes, how do you govern—how do you run the new society?

Factories have to be organized and coordinated, and agriculture has to be collectivized. But then, what is the relationship between the managers and the managed? What are their roles, and how does one become the manager? And how does one manage? Does one manage in the same way as the capitalists, or how is socialist management different from capitalism? These are very concrete day-to-day life experiences that people need to deal with.

Long story short, the Cultural Revolution was the most comprehensive, the longest-lasting, the most thoroughgoing, and the most in-depth experiment of the working class to explore how to be the real master of society. And that’s the significance of the Cultural Revolution. I witnessed that, and I saw all kinds of ups and downs.

[comra]: What makes the Cultural Revolution such an important topic in modern Chinese history?

Fred Engst: First, the New China brought education to the whole population. The writing of history was no longer a privilege only a few had. So we had a whole population that was able to write its own history. For today’s people to be able to study that history is an enormous amount of wealth of information. That is unprecedented.

This was the most complex struggle in human history—complex in the sense that every type of conceivable ideology in society today, any kind of ideology, had a chance to play. Then what kind of ideology really wins? And how do you reach consensus? The working class and peasantry were not born to know how to be the masters of society.

And how do you distinguish and correctly handle two very distinct types of contradictions? That between the working class and the old ruling class? That’s easy. You know who the old landlord was. You know who the old capitalist was. But what about the contradictions among the people?

There was a phrase during the Cultural Revolution called “capitalist roaders.” People in the leadership went down a capitalist road; people in the party—the authority—went down a capitalist road. But how do you know what a capitalist road is? It’s not like they had it written on their foreheads: “I’m a capitalist roader. Come on, shoot me.” Nothing like that. So how do you identify anybody in the leadership, whether they’re going down a capitalist road or a socialist road?

Of course, in hindsight today, we know what it is. But you have to go back in history and see what the actual struggle was—where was the fork in the road? And actually, on this road of building socialism, there are many, many forks. When people have different opinions—different ideas—does it make them capitalist? Or are they just people who have different opinions?

It is unimaginably complicated. Also, people born in the old society had all kinds of backward ideologies that they picked up as they were growing up. I mean, feudalism, imperialism, and capitalist ideology don’t just die away.

[A new society] has a lot of baggage from the old society—in ideology, in customs, in habits. Thus, the working class has to struggle and try to figure out what ideology—what kind of line and practice—is for the interest of the working class in the long term, and what is just for short-term benefits, or what is the leftover from the old society?

Basically, it comes down to the working class having to change itself in the process of changing society. These two things go hand in hand. And the big lesson—if I can say so now—is that the working class really needs to learn how to overcome factionalism within its own ranks. That’s what caused the demise of the Cultural Revolution, because once the working class rises up trying to be the master of society, they split into different factions and they ruthlessly fight each other. Some people resorted to violence, and in some places it was pretty brutal, pretty bloody.

Today, that’s all you hear about it. But you have to analyze it through the lens of that being the growing pain of the working class learning how to be the master of society. You cannot throw the baby out with the bathwater. There were a lot of mistakes made, but there was a lot of experience gained. It is a tremendous wealth of experience that needs to be summed up for any future working-class struggle, because we will make the same mistakes. History repeats itself. But once we learn this history, hopefully we can make fewer mistakes.

[comra]: What was the role of women in the Cultural Revolution?

Fred Engst: It’s not just about the Cultural Revolution alone, but the Chinese Revolution as a whole. You had the Chinese people who came from a long feudal society—the obedience to authority, the oppression of women, and the hierarchical way of society were very deeply ingrained.

And the Cultural Revolution provided a tremendous destruction of that kind of feudal weight and that oppression of women. The oppression of women was broken through land reform, through collectivization.

But also during the Cultural Revolution, you had so many women Red Guards and women rebels, and they were really just equally capable of challenging authority. And they were just totally free to do that. That has never before existed on such a mass scale.

[comra]: Looking back on your time as a Red Guard, what is one moment that sticks in your mind the most?

Fred Engst: In 1966, our family moved to Beijing, and after a while, I went with my cousin to a coal mining town, just like Red Guards would travel to a coal mining town. I stayed there for about three or four months. I was only 14. We went to the mines and worked with the miners.

So one day, another worker from a different mine came to our field and said, “God damn it, those conservative factions tore down and burned the national flag. They are counterrevolutionaries! We’ve got to go condemn them!”

So we all got excited. And then after work, we got off the mine, went to the bathhouse, cleaned up, changed our clothes, and marched to the coal mining headquarters. There were hundreds of workers, and they were all arguing and talking. I just went, “What happened? What happened? What happened?”

It turned out there were two factions of workers: one rebel and one conservative. And the conservative faction felt like the factory managers were revolutionaries, and that the others attacked them and were counterrevolutionary. The rebel faction said that the leadership were capitalist roaders and that they upheld the capitalist line, and that they were going to rebel against them.

The argument got heated up. So then the conservative faction got so angry with the rebel faction that they tore down the rebel flag and put it down on the floor. Turns out it wasn’t a national flag but the rebels’ flag. And the rebel said, “We are the revolutionaries. You tore down our flag and that defines you as reactionary.” It was just that logic.

So you can see, the working class needs to learn how to be the master of society, and there are these small issues. Because of the Cultural Revolution, people in China had a sense that they were the masters of society. So they dared to speak up, and they dared to criticize the leadership. They had what’s called big character posters.

But today, where’s the place for people to speak up other than on “election days”? You can support certain candidates, but have no arena, a space where people can discuss their schools, their factories, their farms, their institutions, a space where everything goes practically. I saw this in the factories, and I saw it in schools. You had your big character posters criticizing the leadership or some other faction—you had factional debates—and you put your poster up and the other guy says, “No, I don’t like that.” He writes something else and covers it up. It was so confusing. People had to sit through all these opinions and figure out what the real issue was.

That’s the relevance for China and the Chinese working class. They were determined to control their destiny. However, due to immaturity, they got stuck in factional infighting and let the capitalist roaders take over.

[comra]: Few modern historical narratives are as highly contested as the Cultural Revolution, but why?

These so-called capitalist roaders were also former revolutionaries. They made great contributions to the Chinese Revolution, the War Against Japanese Aggression, and the war against the Nationalists [Chinese Civil War]. So these were former revolutionaries, but later on, they treated the people as their subordinates. They saw themselves as the masters rather than the servants of the people. Class struggle in China built up to that extent—that sharp disagreement about which way to go forward for China.

China was a very backward agricultural society. Before 1949, roughly 80% of the population engaged in agriculture, and we had a very poverty-stricken society that went through a hundred years of warring warlords fighting each other and imperialists plundering China. So it was a country ravaged by imperialism and feudal warlords fighting each other. To then overthrow imperialism and capitalism was a big achievement. But thus, the people who joined the revolution before ‘49 had all kinds of reasons to join the revolution. They could be against feudalism, but not capitalism. They could be against imperialism, but not capitalism, and so on and so forth.

The revolutionary ranks were made up of people with all kinds of different ideologies, so that during the revolutionary war, it was not clear what their true motivation was, because everybody was fighting a common enemy. But once that common enemy was overthrown, the differences among the ranks within the so-called vanguard party—the differences in ideology—started manifesting themselves.

Then China started condemning the Cultural Revolution, and that made me realize, “Wait a minute. I understand why you condemn it. Because you were the target! You were the capitalist roaders. And that’s why you condemn it.”

You know, after the Cultural Revolution, there was something called “scarlet literature” and sobbing, crying about how [intellectuals] were mistreated by the Red Guards, by the Cultural Revolution, and the whole anti-intellectualism. I found that laughable and sad at the same time. Because part of all this so-called persecution against intellectuals was not done by the state. It was the infighting among the intellectuals themselves. I mean, imagine university professors fighting each other. Who do you blame?

[comra]: You jumped straight from the Cultural Revolution into the cold waters of the US. How can one imagine this drastic contrast?

Fred Engst: I found it really puzzling when I first went to the US. And in the US, they always praised themselves as champions of democracy and freedom. So I said, “Well, I experienced the Cultural Revolution. Why are you condemning the Cultural Revolution? Isn’t that democracy?” People responded, “No, it’s not.” And when I asked, “Oh, what is democracy then?” they just said, “Elections!”

Okay, if elections are democracy, then what about the factories? I mean, I experienced a real, lively, daily type of democracy. We argued, debated, and we talked about freedom. I mean, of course, there’s a limit to what you can freely say.

In the US, you can say anything you want, but you’re not free to criticize your boss. I mean, you could criticize your boss, but then you’d [be fired]. You’ve got to pay a price for it. So, I find it really puzzling when Western scholars, especially, are so into US democracy, freedom, and Western ideology, and condemn what was going on in the Cultural Revolution.

The portrayal of China as an authoritarian regime is so contrary to the daily lives of the people. And that’s what’s incredible. I was working in a factory during Mao’s period for five years, and then I went to the US, where I worked in a factory for more than a dozen years. And the contrast cannot be more startling. After my five years in that Beijing factory, I don’t have a single memory of the workers being afraid of the people in the leadership. When the factory managers and people in the top leadership came, the workers just said, “God, I haven’t seen you in a long time,” in a sarcastic tone, as in, “You are so divorced from the masses.”

To have an impact on what’s going on in the factory, you cannot just go by your own grievances. To have an impact, your grievances must be shared by a whole lot of people. So you have to have some kind of consensus among the workers, saying, “No, this is wrong.” Only then can you really make a change.

However, it was a revolution under the dictatorship of the proletariat. What does that mean? That means you could not challenge socialism. If you had said, “Down with the Communist Party, down with Mao,” you would have been condemned by the population. Before the cops would’ve come to arrest you, you would’ve been beaten [by the people]. People were really into defending the new society.

[comra]: What do you think is the most dangerous or most common misconception about the Cultural Revolution era?

Fred Engst: Misconceptions? There are a lot of them. I’m not sure which one is the most dangerous. What does that mean? I think it depends. If you are on the side of capitalists, then of course you condemn the Cultural Revolution, that is the so-called “tyranny of the majority,” the lived experience of the “tyranny of the majority.” And if you’re afraid of the majority, it’s because you’re a capitalist; that I can understand. But if you are coming from a working-class perspective and condemn the Cultural Revolution, you are just totally misinformed.

I was really confused in the 80s and 90s because of what happened in China—all the denunciations of the Cultural Revolution, of Mao, made me wonder whether I was brainwashed, whether I was duped, whether I was just naive, whether I was just believing whatever I heard first and then sticking to it.

So I’ve been challenging and questioning my understanding [of the Cultural Revolution], but I cannot negate my experience. I cannot erase what I saw. Quite often, what we see is people calling it chaotic, crazy, almost like religious fervor. And all that means is that they don’t understand what happened.

They focus on Mao’s personality cult. But is that the main contradiction in Chinese society? It’s not, right? When we try to overthrow feudalism and feudal ideology, it doesn’t happen overnight. So the people who joined the revolution had all kinds of motives. And the workers who rebelled against the capitalist roaders might’ve quite often used feudal ideology as their weapon because that’s what they knew.

Okay, so you got to figure out what the main contradiction is. The working class and the movement can make all kinds of mistakes. You cannot hang on to that one mistake and denounce the whole movement. You have to step back and see, “Okay, overall, are they among the forces who pushed the working class towards greater emancipation, or are they hindering the working class towards its path to emancipation?

Source: Comra