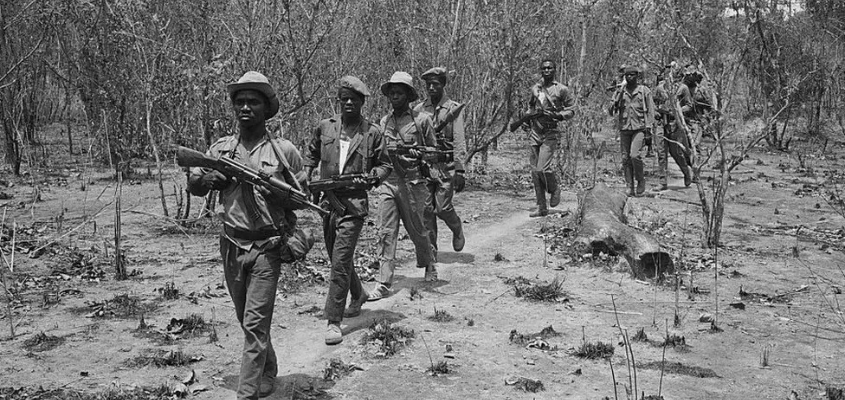

As a small group of revolutionary guerrilla fighters trudges down a jungle path, they crave a chance to rest. Though none of the comrades have eaten in two days and their water supply is running low, it is imperative that they stay on the move to elude enemy combatants. They cautiously pick their way through the bush and ignore the strain of carrying rifles that seem to grow heavier with each step.

Through the palm fronds they are able to see a small village just ahead. One of the comrades steps carefully into the clearing and gestures toward a young woman carrying a bucket of water. There is panic in her eyes as she places an index finger over her lips to command silence. With hand gestures she directs the comrades to an area behind a cluster of small dwellings.

When the fighters and the young woman are safely concealed, she explains quickly that the oppressor regime’s soldiers have been patrolling the area. There is no need for the fighters to explain their mission. The young woman and the other villagers she quietly summons to provide food and water to the freedom fighters already know the enemy and they are committed to the success of the revolution.

Of most significance in the imagined scenario described above (which could occur in many countries in the Global South) is that everyone in that society, whether they be guerrillas, peasants, itinerant merchants or anyone else, intuitively if not consciously understands that the territory they occupy is theirs by right, and a clearly identifiable tyrant, settler minority or brutal regime deprives them of the opportunity to reap the full benefits of their land. Many icons of revolutionary struggle like Guevara, Cabral and Fanon have contemplated this type of society when they have spoken of revolutionary strategies, and this has caused frustration and confusion for those people of African descent in the U.S. who have wanted to wage revolution, but because they are a minority population not indigenous to the territory they occupy, their circumstances are very different from many areas where liberation struggles have been fought.

Specifically, because of the western hemisphere’s indigenous populations and the complicated history of settler colonialism in this country, for many Black people in the U.S. there is no universally shared belief that the land they occupy is rightfully theirs, and consequently there is no universal sense of loss of ancestral land that might fuel a fight to liberate territory. Additionally, because of devious deception, miseducation, gaslighting and propaganda, most Black people in America are unable to accurately identify their enemies. The only widely shared conviction is that Black communities suffer. Consequently, it comes as no surprise that Black people in the U.S. lack the unity of experience, thought and action found in societies where revolutions occur in an uncomplicated social, political, economic and historical context.

Because of their confusion and diversity of thought, Africans in the U.S. have alternately experimented with strategies to relieve their oppression that involve not only revolution, but also assimilation, integration, separation, repatriation, alliance, reparation, “delineation,” election, and in some cases racial treason. In this country there are Pan-Africanists, cultural nationalists, Democratic Party stalwarts, Black Republicans, so-called Foundational Black Americans, Marxists, New Afrikans, and many more. As a whole, Black people in the U.S. not only lack a unified political focus but also demonstrate no evidence that they will find one in the near future.

The Black Panther Party, the Black Power Movement, the New Afrikan Independence Movement, and many others have manifested instinctive as well as conscious resistance to oppression, and they have done what revolutionaries are expected to do with respect to their posture, rhetoric and programs. Yet, because of their circumstances, it has not been realistic for these groups and movements to single-handedly defeat the state and the capitalists who run it.

This has been a source of frustration for those Black revolutionaries who are mentally and emotionally wed to the notion that the target of their fight must be the government or regime that most directly dominates them. However, as a minority group in the U.S., Black people’s options for struggle are limited by many factors, including the chronic and perhaps incurable racial chauvinism of white workers, which limits even prospects for successful multi-racial class struggle in the U.S.

Black people may lament the fact that they are a powerless, exiled minority population with no inherent rights to the territory they occupy. But why mourn? Why not embrace the idea that their historically determined role may not be to (at this moment) seize North America, but rather to serve as revolutionaries at large rendering service to battles against imperialism elsewhere? Africans in America are part of something larger than the domestic struggle.

Huey Newton explained:

“The more territory we liberate in the world, the closer we will come to an end to all oppression. The common factor that binds us all is not only the fact of oppression but the oppressor, the United States Government and its ruling circle. We, the people of the world, have been brought together under strange circumstances. We are united against a common enemy.”

For organizations like the All-African People’s Revolutionary Party and Black Alliance for Peace, international political work is nothing new. They are part of a long tradition of Black struggles for international solidarity. Nevertheless, the idea of a Black American “nation within a nation” that struggles for its own freedom here in the U.S. endures even among many who work on the international front. For purposes of managing expectations, it may be worth frankly acknowledging that, on their own, Africans in the U.S. will not bring about a day of glory when freedom fighters march triumphantly through the streets of Washington D.C. after overthrowing the government. This does not mean Black people in America lack the capacity and responsibility to fight. It is simply a question of how they can do it most effectively.

Black people in this country are in a unique position to in many ways strike lethal blows against the U.S. empire from within the proverbial belly of the beast that will contribute to victories in other countries. Already the campaign against U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM) has through the years become practically an institution that has almost certainly limited the expansion and impact of the U.S. military presence in Africa.

Also, the U.S. military can’t put boots on the ground in other countries if nobody wears them, and there is precedent for the Black community discouraging its young men and women from enlisting when there is a high risk that they will be asked to die for oil or other imperialist objectives. In addition, Black people in this country can directly engage members of the military and counsel them against participation in imperialist intervention.

More generally, when we observe that attitudes toward ICE raids have changed as more people have been able to process that the brutal nature of these deportation efforts is not an abstract idea, and that real people are harmed, we can see how Black people in the U.S. can likewise play a role in raising the level of awareness of the devastating impact of imperialist intervention on real people in other countries.

Finally, notwithstanding the fact that during an era when so many people have taken their cue from Trump and have approached, or even reached a state of spiritual death, a critical mass of African people in the U.S. are still people with faith in the divine creator, or they at least have a strong commitment to love. Even without conscious effort such people stand as a last line of defense against the broader population’s complete descent into a state of callous indifference or even hatred that gives free rein to unchecked imperialist violence everywhere.

The derivative benefit of giving highest priority to international political work is that the empire will not only be weakened and more vulnerable to domestic revolution, but also, when white workers in the U.S. finally wake up and with their beloved guns seize control of the government and economy, there will hopefully be revolutionary countries in the Global South poised to protect the Black minority in the U.S. from the racial bigotry of the white working class that is unlikely to evaporate simply because they will have won a battle against the capitalists.

There is an urgency to the mission of Black revolutionaries-at-large, because notwithstanding the bluff and bluster of the Trump regime, the U.S. capitalist economy is collapsing by the day. The wild, erratic military attacks on Venezuela and Nigeria as well as the insane threats to attack Cuba, Mexico and Greenland are evidence of the empire’s desperation for resources to bail itself out. The empire is teetering on the edge of a cliff. The moment quickly approaches when Black people in the U.S. will be in a good position through their international political work to help give U.S. imperialism a final good shove over the precipice and into the abyss.

Mark P. Fancher is an attorney and writer. He can be contacted at mfancher@comcast.net.

source: Black Agenda Report