Comandante Pablo Beltrán

Now that Camilo’s remains will finally have a dignified burial at the National University, it is important to highlight the foundations of his ideological and political legacy, which make him one of the immortal stars that illuminate the path of humanity.

He fell in combat in the ranks of the National Liberation Army (ELN) on February 15, 1966, just after turning 37. He was already a priest at 25 and a sociologist at 29, the same year that Saint John XXIII was elected Pope and is remembered for the transformation he brought to the Catholic Church. From him, Camilo learned that “the Church belongs to everyone, but especially to the poor” and that “we must emphasize what unites us, not what divides us”—precepts that opened the door to dialogue between Christian and Marxist humanism, undermining the foundations of the Cold War, sustained by capitalism and its Western empire, with the aim of annihilating socialism.

When Camilo arrived to study sociology at the University of Leuven (Belgium) in 1955, the armed rebellion against French colonialism in Algeria had erupted a year earlier. This rebellion, which triumphed in 1962, received widespread support from the youth of that era, and Camilo participated in that solidarity. He also became deeply involved with the movement of European priests who chose to live like the poorest and most excluded people, in stark contrast to the luxuries and privileges enjoyed by the Church. In these schools, he learned the importance of the rights of the people and the struggles for national liberation, and, as he put it, “to rise to be one of the people and learn from them.”

A year after returning to Colombia, in 1959, he founded the Faculty of Sociology at the National University. That same year, the Community Action Boards were created as a tool to organize a social base opposed to the revolution. He was offered the leadership of this organization, an offer he declined. This counterinsurgency effort was complemented by the creation of the Lancers School, specializing in training counterinsurgency soldiers. They also implemented agrarian reform projects, which were part of the “Alliance for Progress” orchestrated by the United States.

All these plans were orchestrated by the National Front, a pact between the two oligarchic parties to alternate in government. This was intended to fulfill the words of President Alberto Lleras (1958-1962)—the first president elected under this pact—who, faced with the popular rebellion that erupted in response to Gaitán’s assassination in 1948, had declared that “every revolution needs its own counter-revolution.” This was the country Camilo encountered upon returning from Europe, where the tragic echoes of the war against the people, unleashed by the oligarchy and the empire, were still reverberating. This period was studied by several intellectuals and condensed in the landmark book “La violencia en Colombia” (Violence in Colombia), of which Camilo is one of the authors.

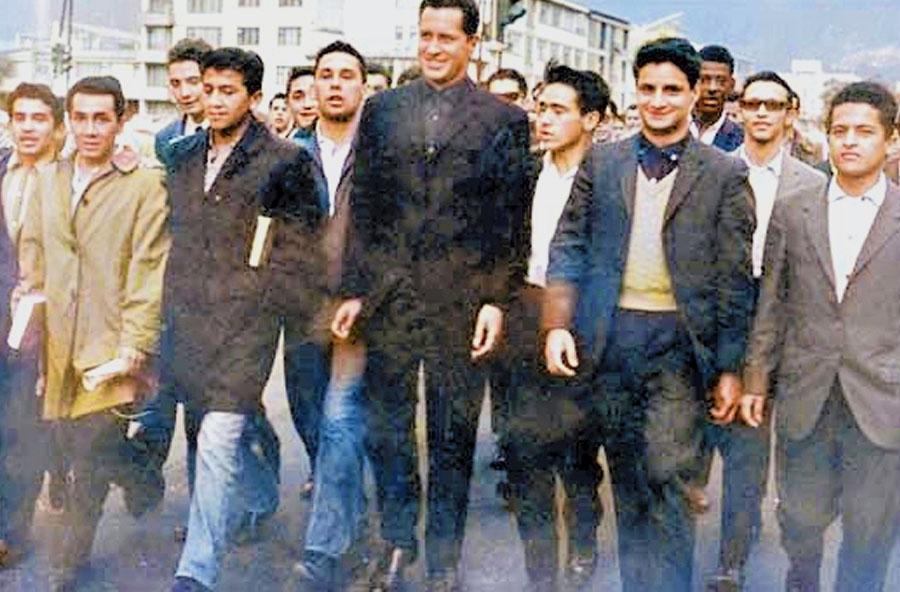

Camilo’s career at the National University encompassed teaching and serving as Chaplain from 1962 onward. He also worked to connect students with the realities of the people, both in Bogotá and in remote regions of the country. Camilo absorbed a deep understanding of the national reality, imbued with the spirit of renewal that marked the Church at the Second Vatican Council, led by Pope Saint John XXIII.

This spirit of concord contrasted sharply with the atmosphere of war imposed by the American empire, which, in its aggressions at that time, was unleashed against Cuba, Vietnam, and the Dominican Republic. This included the bombing of rural areas in Colombia in May 1964, where pockets of resistance to oligarchic violence prevailed. Camilo denounced this aggression and spearheaded a broad national and international solidarity movement with the besieged communities.

In one of his 1964 writings, titled “How Pressure Groups Exercise Government,” Camilo envisioned the organization of the people at the bottom, the majority, so that they could form the government and thus “make Colombia a true democracy.” Long before this, he had a clear understanding of his class affiliation, siding with the impoverished and excluded. In 1965, in his “Message to Christians,” he stated that “It is necessary to take power away from the privileged minorities and give it to the poor majorities. This, if done quickly, is the essence of a revolution; the revolution can be peaceful if the minorities do not offer violent resistance.” In this same Message, he argued that Effective Love is making the revolution and that for Christians, making the revolution is an obligation.

Source: https://eln-voces.net/2026/02/16/un-inmortal-60-anos-despues/