Originally published on the website of Kurdistán América Latina, an article by Alberto Colin Huizar depicts the struggle and legacy of Sakine Cansız and her contributions to “revolution within the revolution”.

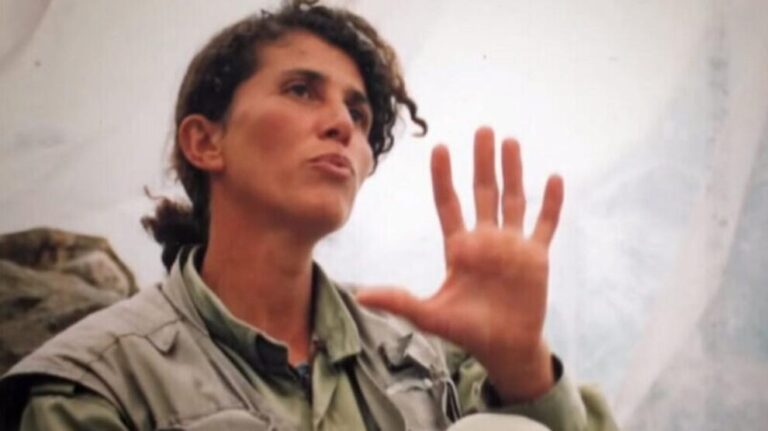

January 9, 2024 marked the eleventh anniversary of the cowardly assassination of the three Kurdish activists, Sakine Cansiz, Fidan Dogan and Leyla Saylemez by a Turkish intelligence agent, who fired his gun inside a Kurdistan Information Center located in the center of Paris, France. Since that terrible episode, the names of the struggle of the three comrades massacred are inscribed as an act of memory in a slogan that the internationalists usually shout when they march through the streets: Sarah, Rojbin, Ronahi, Jin, Jiyan, Azadi. This murder, still unpunished, has a historical relevance for the Kurdistan Freedom Movement, but particularly for the Women’s Movement for being a specific attack against women who integrated structures in the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), mainly Sakine, who was one of the founders of the party and a pioneer in women’s organization in the Kurdish revolution.

During her lifetime, Sakine wrote a three-volume autobiographical work published in Turkish entitled Hep Kavgaydı Yaşamım (All My Life Was a Struggle, Descontrol Editorial, Barcelona, 2018). In the first volume of just over 400 pages entitled “Born in Winter,” Sakine narrates various stages of her militant trajectory, from her childhood in the village of Dersim where she was born in 1958, to her imprisonment in Amed by Turkish repression in 1979. The book stands out for showing in extreme detail a complex story of the emergence of a revolution: that of the Kurdish people. The accounts of Sakine’s life are set out with superb discursive skill. She describes in words the social and political context in which the family and militant relationships unfold, crossed by reflections and critical assessments of the author herself. In this sense, it is a memoir of the Kurdish struggle. The level of description and the fidelity of the memories is also impressive, given that the book was written with the notes that Sakine wrote in the 1990s, which she carried in her backpack when she traveled through the mountains of Northern Iraq with her military unit, in the midst of the guerrilla war.

To the eyes of an anthropologist, the work constitutes a valuable ethnographic record of the emancipatory process of a people, narrated from the very codes of Kurdish culture. In the first part, Sakine introduces us to three key dimensions of her formation: Dersim, the family and women. To understand her locus of enunciation, the author introduces us to each of the people who marked stages of her life: her father and mother who were survivors of the genocide by the Turkish fascist state[1], community life, and her understanding through the Zaza language she acquired in the family. Sakine learned Turkish and German at school, but accepts that it was “just torture”. As in many countries where colonialism was installed in the social structures, Kurdish children were also punished for speaking their mother tongue at school. Just as in the case of Latin America, nationalism entered the classroom with force through writing and linguistic homogeneity, and teachers, many of them fascists, were the vehicles for its transmission.

Sakine narrates that her mother, coming from a well-to-do traditional family, had a crucial influence in her identity recognition as a Kurdish woman, in the defense of her own identity in spite of the assimilation of the Turkish state that deepened in those years in the province of Dersim. Her father, on the other hand, was part of the Alevi community[2] and worked as a civil servant for the local government, which resulted in a certain family economic solvency, but also in a certain adaptability to socialization with Turkish people. This religious influence and the discipline of her mother, were lessons in Sakine’s life that showed her both panoramas: the customs of the cultural context in the city and the reaffirmation of the Kurdish by its territorial roots.

When Sakine was still a child, two processes were formative for her political consciousness: the early migration of Kurdish families to Germany and the systematic police repression in Kurdistan. In detail, the book describes the first repressions Sakine witnessed in her village, with systematic police presence and bans on cultural events, but also recalls those young men who opposed the state. The concepts of revolution, leftism, communism resonated in her mind, but without yet finding a concrete meaning. In general, in Dersim there was a shared sense of opposition to the Turkish state, which had been historically violent towards the Kurdish population of this region. Such was the domination that, for example, the name of the city (Dersim) was changed by the government to Tunceli, which means Iron Hand in Turkish. Since the 1960s there were already signs of insurgent actions and radical political groups as well. Sakine learned early on about these processes from her teachers with whom she talked at school and from interactions in the neighborhood that she came to understand as she observed how young people were organizing politically against the fascists. In this sense, Sakine notes that:

Rebellion was sown in the midst of our childhood. The events unfolding in front of our eyes messed up our emotional and mental world. We learned new things. Already in the early days of middle school, more precisely in the first days, I found myself, without expecting it, in the middle of a strike. (p. 57)

These experiences are narrated by Sakine in a way that allows us to understand the historical context and the political actors that were developing at that time. There were armed cells and clandestine organizations that confronted Turkish politics, marked by coups d’état and national ideologies such as Kemalism. While this was happening outside, inside the family, Sakine learned many attitudes from her mother, among them, rebellion and struggle every day, taking care and working with discipline. Some time later, Sakine had to migrate for a while with her older brother and her father to Germany for work reasons. This experience was also significant for the formation of her revolutionary consciousness. The influence of her older brother and his leftist friends who visited the house and talked politics, together with the plays, demonstrations and public meetings she observed in Berlin with the Kurdish community, were seeds for forging her own consciousness of her ethnic identity in a foreign country, where intercultural relations were more latent and otherness was perceptible.

For Sakine, this was the beginning of her rebirth as a Kurdish woman with a maturing political perspective. When she returned to Dersim the following year, the critical and leftist youth, among whom Sakine was included, bet on turning the classrooms into an arena of struggle to fight the fascists. Several demonstrations, student strikes and repressions took place, of which almost the whole town became aware. However, at the community level Sakine had to deal with traditional marriage customs through agreements and compromises, as one could not freely choose a courtship. During youth, it was common in Dersim for families to generate marriage agreements between daughters and sons without their consent. This situation sparked a long-lasting dispute between Sakine and her mother who wanted to control her and often reminded her: “now you are engaged”, to stop her political activity. This was a struggle that Sakine had to face for most of her youth, as her mother did not see her involvement in the resistance as appropriate. This process resulted in Sakine thinking about leaving Dersim at some point to become involved in political participation elsewhere. There was no turning back, Sakine would be a revolutionary, as she states in her early approach to the resistance:

It is not easy to describe all this, and it is difficult to understand it without having lived it in the flesh. It is not enough to write it down to express the simplicity and beauty of those days and my feelings of yesteryear. As I write it, I feel again wholeheartedly and with full consciousness these feelings that I experienced back then. It was beautiful to arrive without hesitation and authentically to a conviction, to an ideal, going through contradictions and struggles. I lived it as a great joy and I repeat it again out loud: I am the happiest person on earth to be participating in this struggle (p. 120).

Ideological training became a principle of the struggle since other Kurdish militants told young Sakine about the importance of Kurdistan and the national liberation struggle. Understanding the situation of the Kurds became almost an obsession in Sakine’s life. She talked about it at school, formed study circles with friends, discussed it with her uncles and neighbors. “Training was for us the most important part of our work,” Sakine writes about these early years of militancy. Gradually the group grew in numbers. The youth were joining together in Dersim and there was talk of the existence of “Kurdish revolutionaries”, while the state repression was deepening. From this time on, the social values surrounding women’s participation in these political groups changed as the presence of women comrades like Sakine was noticed. Her involvement was an issue that caught the attention of other women, even from other villages, who saw in Sakine an exceptional commitment.

As organized Kurdish groups grew in the region, the situation was increasingly complicated in Sakine’s family: “families, at that time, had more influence than state institutions”. Her mother’s vigilance increased, Sakine was repressed for attending training groups and was forbidden to visit her at home. The only solution she found to this problem was to leave. Meeting family expectations to accept marriage was a burden for Sakine. She did not know her suitor well, nor did she have a political connection to him, as he was a supporter of the Turkish left. For her, marriage represented an obstacle in revolutionary work. In a way, political training and conviction played a major role in her worldview: “our ideology questioned the prevailing system with all its ways of living and relating to each other”. Therefore, Sakine assumed with fortitude that ideological struggle makes revolutionary struggle inevitable and decided to follow her path by leaving Dersim against her family’s decision. Sakine traveled to Ankara with the support of her comrades who never ordered her what decision to make, but always supported her. Her stratagem was to marry Baki, a fellow member of the group, to avoid being harassed with the insistence of marriage. In Ankara she continued her revolutionary work in the organization, met people linked to Kurdistan and was ready to face the challenges of the future.

Due to the precarious conditions of the group with whom Sakine came to live, it was necessary to get a job. With that salary they could raise money to pay the rent of a space that would function as housing and organizational space for political tasks. Sakine admired the proletarian class; for this reason, she decided to look for a job in a factory on the outskirts of the city. She wanted to live like a worker. Soon she found an opening in a chocolate factory. She quickly got her first job. The idea was to get to know the work culture and to do political work with the women. There she met a couple of Kurdish women who were hiding their ethnicity in a city where they were usually stigmatized because Kurdish identity was full of prejudices spread by Turkish society. Sakine then engaged in sloganeering, propaganda and agitation work inside the factory to forge a political consciousness among the workers that would also result in the defense of rights and rebellion against the boss.

In the book, Sakine constantly discusses the personal dimension because it is eminently political. Thus, she intersperses between accounts of her public militancy and her daily life with her comrades in the private sphere. For example, she relates that the political positions of the members of the group with whom she lived were diverse and this bothered her, particularly Baki, who also felt a certain authority over her because of her marriage. Her relationship with him was uncomfortable because she had fled a forced marriage in Dersim and this man who had been her exit option now wanted to force her into a traditional relationship. This accentuated the differences in the household. It should be noted that at that time in Turkey there were a number of radical leftist groupings with different aims, but the national question of Kurdistan was in doubt for many militants. On several occasions, they debated with Sakine whether Kurdistan was a colony or not, what were the objectives of the struggle as Kurds, etc., aspects that triggered inconclusive discussions among the members of the group. Sakine always remained firm in his criticism of colonialism and to dedicate the struggle to the Kurdish question. This ideological break was decisive because Sakine thought that “the revolutionaries of an oppressor nation had other tasks than those of an oppressed nation”, therefore, the ideals of the struggle had to arise from the historical necessity of their own people.

Some time later, Sakine found the companionship she was looking for when she attended a meeting of UKO, the national liberation army that was formed in 1973 around Abdullah Öcalan, at the invitation of a fellow Dersim member. Sakine recalls that at the entrance of the meeting place there was a sign that read: “only Kurds accepted”. Sakine knew this was a good sign. Coming with a female companion and being the only two Zaza-speaking women in Dersim, they listened to the discussions and agreed with the analyses. Soon they participated in an assembly and the companions noticed Sakine’s speaking and critical arguments, which left a good impression on the group. This was the first approach with a radical Kurdish association, which claimed the armed struggle. At the same time, these meetings allowed her to observe the contradictions of the Turkish leftist groups that tried to co-opt her, mainly Baki, who was a member of a group called HK (people’s liberation). This problematic relationship with Baki lasted for several months and occupied a good part of Sakine’s youth, among dilemmas, discussions, fights and sadness that transited throughout her stay in Ankara and Izmir. Nevertheless, her goal remained firm: to work for the revolution in Kurdistan.

After working in a couple of factories from which she was fired for her active work as a workers’ agitator, she found a place in a textile company. Sakine was aware of the importance of organizing the working class against the powerful, but also of bringing the Kurdish question into the discussions, seeking solidarity and raising awareness of colonialism. This was what she could contribute to the workers’ struggle. In a few weeks she managed to form a group. In addition, she was quite critical of the textile union that did not contribute to improving the working conditions of the employees and when she was elected as a representative of the women workers, the employer tried to terminate her contract, which is why they organized a strike. “We will break the chains, we will defeat the fascists,” they chanted as they sat on top of the factory machines. The resistance had begun, but repression soon followed. The next day the protest was repressed and the police took several workers prisoner, among them Sakine, who was beaten and imprisoned for one night. When she was released the next day, they returned to the factory and launched a hunger strike to demand the reinstatement of 75 workers who had been fired without severance pay. The protest began and almost immediately Sakine was arrested again by the police along with eleven other people. Sakine was taken to prison along with another fellow worker. This was the first prison experience in Sakine’s life, although she was pleased that news of her arrest and hunger strike had spread throughout Izmir.

The prison could not stop Sakine’s political work. The other prisoners in Bacu prison knew about the story of Sakine and her companion, whom they called “the politicians”. Inside the prison, they forged a routine of exercise, study and ideological work that surprised the other prisoners. On May 1 they organized a hunger strike in solidarity with the protest actions carried out by the workers in Istanbul and on May 8 they held a tribute to Leyla Qasim, a Kurdish activist who was killed in Iraq. This woman was a source of inspiration for Sakine for her courage and persistence in her struggle. In her cell she had a picture of Leyla carrying a gun and a canana. “Women and guns, women and war, women and the struggle for national liberation, women and death; all of that had a very special meaning,” Sakine reflects. After three trials and a few months of imprisonment, Sakine was released and learned the news of the murder of Haki, one of the most prominent comrades within the organization of revolutionaries for Kurdistan. Apparently, his murder was at the hands of HK militants, an organization in which Baki participated. This betrayal was the key for Sakine to break all ties with Baki. Without much thought, Sakine took her suitcase and traveled with another comrade to Ankara. The divorce proceedings would take place much later during one of her visits to Dersim when she told her mother the truth.

At this moment of Sakine’s life she started her integral involvement in the Kurdish revolution. In Ankara she lived with Kesire, another of the fundamental comrades of the first circle of the organization with whom she lived unforgettable moments. One of those moments was when she met Abdullah Öcalan in the garden of the Faculty of Political Science at Ankara University. Sakine recalls in detail that Öcalan “was an individual who stood for principles, revolution, internationalism, love for the homeland and relentless struggle.” During his stay in Ankara, Sakine occupied the time for her training, so she took advantage of the conversations where Öcalan was in the different spaces of the organization and at the Faculty of Law. According to the tasks assigned to her, she returned to Kurdistan to fulfill her role in the organization. She started political work with Kurdish families in the Elaziğ region. They welcomed her and showed her how they were organized in the neighborhood. The atmosphere was much more empathetic to the Kurdish revolutionaries because there was already a history of anti-fascist struggle in the area. Her task was to establish training groups or committees for the generation of cadres to act at the local level in the company of the families. The need for “mental awareness” was the purpose of establishing these relations; that is, to strengthen the ideological work and support bases.

Some time later, Sakine was sent to Bingöl to carry out this same type of work, but with the delimited mission of emphasizing work with women, although there was still no specific concept to support this task and it was conceived as part of the general objectives. From this moment on, the emphasis on work with women took on greater presence, because “since women were the most oppressed, they also had the best conditions to become revolutionaries”. The program of organizational work was thought out by Sakine with a certain autonomy, as it depended on a collective assessment of what was best to do, given the context analysis they carried out in the field. In Bingöl they tried to carry out actions in a sense of community support and ideological formation with women, but they also used revolutionary violence to fight the fascists in the village. After a few weeks there were already about 25 women in two training groups who were willing to carry the ideals of the struggle both in the families and in the schools and neighborhoods. When Öcalan went to visit them in Bingöl, they called a large meeting where he was happy to hear about their work.

It is very interesting how these works in the territory, directly linked to the families and their daily life, allowed cadres like Sakine to have a deeper understanding of the daily problems of the people and to look for strategies to boost revolutionary consciousness. Also notable is the level of criticism and self-criticism Sakine exercised on her own foray into the communities and neighborhoods to spread the need to struggle in an organized way as Kurdish people. Nevertheless, touring the villages of Kurdistan and talking to the people created a new sense of belonging for Sakine and strengthened her conviction: “it filled me with pride and happiness to be part of the struggle for this country, whose remarkable poverty sometimes brought tears to my eyes.” This gave Sakine a broader view on cultural forms and religion, but also on how inequality operated in the villages and in what ways organizing for liberation could be empowered. Although notions such as gender equity and women’s liberation were not yet common, Sakine’s work with women, especially those of a certain intellectual level, had enormous effects.

Between 1977 and 1978 Sakine was dedicated to work in these regions of Kurdistan. They formed a good number of cadres in the neighborhoods and regional committees in each of the cities, with more and more popular acceptance. So much so that on different occasions Öcalan went directly to these places to hold mass meetings with the organized groups and motivate them to join the struggle. They talked about the history of Kurdistan and the heterogeneous composition of its society. They read texts on the history of communist parties in the world and various writings of Lenin. Although on several occasions the police were stalking such clandestine meetings, most of the time Sakine and her comrades managed to dodge any suspicion. They applied a myriad of strategies to evade surveillance and state operations. They would sometimes change addresses to live or meet, burn physical evidence of pamphlets and communiqués, circulate weapons and ammunition in different locations, and regularly posed as students when they arrived in a new neighborhood.

For Sakine, the covert political work worked well in the schools, from those specializing in the arts to the health colleges. Many young women students joined the movement during these years and counterbalanced the propaganda carried out by the fascists. On one occasion, the group in charge of the organization’s military actions carried out an operation against the fascist mayor of Bingöl. During the escape, some comrades were wounded. When they managed to reach the apartment and hide, Sakine had to heal one of them from a bullet wound. Feeling the pain of the colleague was very hard for Sakine who started to cry. Other colleagues reproached her that she was too sensitive, that she had to be “strong”. During this event, Sakine also reflected on the emotional dimension as something that is also part of the revolutionary struggle and therefore had to be accepted, because “when you love, strong emotions are inevitable”. She criticized her comrades for their comments against her, but accepted that in the revolutionary struggle there are certain costs to be considered.

With this social base established, it was decided to create a body with a certain democratic centrality. Sakine was present at the Founding Congress. It was attended by all the most important cadres of the movement, the “brains” of the revolutionary process. Sakine and Kesire were the only two women at this historic event for the Kurdish people. In a first long and profound speech, Abdullah Öcalan spoke about the conditions of the national liberation struggle and what kind of strategies had to be forged for a Leninist organization. A draft political program and a statute were drawn up. Afterwards, the reports of the work that each one coordinated in each region were poured out, which allowed for a more accurate diagnosis of how the struggle was being approached in all of Kurdistan. From that moment, Sakine took the floor and spoke of what they had done in Elaziğ, placed the emphasis on the work with women and was critical that this objective had not been enhanced in any place where the males did not even involve their wives or sisters in the revolutionary work. Once the meeting progressed a minimal party structure was established. Öcalan was elected as Secretary General and committee representatives were elected by region, as well as the name: Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). Some ideas for the flag were sketched out and a commission was charged with drafting a communiqué. With this event the PKK was born, although it remained a secret for some time until it was made public through the dissemination of the text.

After the founding of the party and in high spirits, Sakine traveled to various parts of Kurdistan with the firm idea of strengthening the organizational spaces through local cadres and committees in the face of the growing climate of repression by the Turkish state, which was concerned about the emergence of the Kurdish movement. However, “the struggle for national liberation took root and continued to develop […] the people of Kurdistan had found the path of resurrection. The fire of freedom spread”. In particular, Sakine had the idea to ask her colleagues in each village where she worked to write something about the women of their village, their particularities and ways of life. This input was very relevant to be able to have an information base with which to start the organizational work of women as a particular objective of the party, as she had the support of Öcalan and the Central Committee for this task. This was the beginning of the Women’s Committee that was coordinated by Sakine, which represented the first formation of a particular structure of Kurdish women: “That was very welcome news. I was nervous and happy. To raise the women’s movement!” she recounts with emotion in the book.

The first task Sakine had was to start a research to gather knowledge about theory and practice of women’s movements around the world, from the past to the present, in order to draw conclusions for the case of Kurdistan. The revolutionary organization of women already had certain concrete elements in Dersim, Bingöl and Elaziğ. This was the beginning of the women’s movement that today, more than forty years later, is an example of dignity worldwide. In 1979 Sakine was arrested in her apartment during a police raid. One of her companions had been arrested earlier and had given away the group’s operations. She was tortured and sent to prison in the city of Amed, but her unbreakable spirit could not be stopped by bars.

Reading this autobiographical work is an apprenticeship for the internationalists of the 21st century in at least three ways. First, because it presents very profound aspects of the revolutionary struggle, in this case of the Kurdish people, that can only be explained from an endogenous point of view. This is an example of the relevance of the actors themselves systematizing or producing a story about their militant experiences in order to give a collective meaning to the contributions of each personal trajectory in the construction of other worlds. For several decades, Latin America has had several records of this type, especially in processes of armed struggle. For example, the book by Omar Cabezas on his guerrilla experience in Nicaragua with the Sandinista National Liberation Front (“La montaña es algo más que una estepa verde”) or the work of Roger Blandino in El Salvador with the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (“Y seguimos de frente”). There are also several texts that are not exactly autobiographical, written by the protagonists of the struggles themselves, but which include a broad political analysis with the background of the experience. This is the exemplary case of the writings of Fidel Castro and Che Guevara on the Cuban revolution or the books of the Quechua peasant leader Hugo Blanco in Peru (“We the Indians”). In tune, the texts of Subcomandante Insurgente Marcos of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation in Mexico use diverse narrative tools such as story, metaphor and sense of humor. We must return to writing as a way of analyzing our times and the challenges we face.

A second sense that is striking in the case of “All My Life Was a Struggle” is that Sakine offers concrete evidence of the value of criticism and self-criticism (Tekmil) as the essence of a radical political practice. Throughout the book we can insert ourselves into the author’s subjectivity because she constantly reflects on her praxis, in a way that positions us with respect to her own questioning of the revolution and its contradictions. In this way, the episodes Sakine narrates, which deal with the personal, family, community and political organization dimensions, are crossed by a systematic ideological exercise of criticism that accounts for the daily struggle against the inertias of the dominant system itself in social relations. This is one of the great contributions of the Kurdish liberation movement to the anti-capitalist world, which was raised with exceptional lucidity by Abdullah Öcalan in several writings. Being one of the founders of the PKK, Sakine assumed this exercise as part of her daily life and it served her as a method to discover the traps of capitalist modernity and at the same time to rethink herself as a product of democratic modernity.

Another of the meanings that the book contributes has to do with the exercise of memory about historical events that changed the future of an entire oppressed nation. In Sakine’s work it is very clear that the central point is how women emerged in the Kurdish liberation movement. Sakine’s book is the beginning of a long process of reflection on the vanguard place of women in the path of emancipatory movements. The book shows an initial fragment of the history of the autonomous struggle of Kurdish women that patriarchy has tried to erase. In this sense, knowing from the inside this cultural change, how the women’s movement developed, the challenges they had to face and the positions of men regarding this process are essential elements for understanding the current struggles of women in the Middle East, as well as the dialogues with other feminist or diverse women’s struggles in the world. Since that time they have built their own structures parallel to the PKK starting in 1987 with the founding of the Patriotic Union of Women of Kurdistan and the decision in 1993 to form an all-female army. Since 2008 the Kurdish Women’s Movement has been working on the formation of Jineology, a women’s science that explores from its own perspective patriarchal domination, capitalism and the state to find the foundations of power and oppression. With this exercise, Jineology attempts to offer an alternative point of view to the dominant analyses, considering the oppression of women as the starting point of patriarchy, but also showing with evidence the workings of matriarchal society to tell “the story of freedom,” as Öcalan noted. Sakine’s legacy moves in this direction and we still have much to learn. Her struggle contributed a lot to this “revolution within the revolution”, which was written in the heart of every Kurdish woman who dreams of freedom and of all of us who were somehow infected by the dream of changing everything.

[1] Dersim was the last city to be subdued after the founding of the new Turkish republic. After several attempts to assimilate the region into the new state, Turkey carried out the bloodiest military campaign up to that time. Between 1937 and 1938, a Kurdish-Alevi uprising took place there. The Turkish state reacted with the genocide of more than 60,000 people. Thousands were displaced. Turkey practiced a scorched earth policy. It drowned mothers with their children in rivers and locked the rural population in caves by burning them alive. Atatürk’s (Mustafa Kemal) government was aligned with Italian fascism and German Nazism.

[2] Belief or religion that some consider part of Islam. They recognize Ali as a prophet, hence the name Alevism. In the Dersim region, 90% of its inhabitants are considered to be Alevis, as opposed to the Sunni majority in Turkey and neighboring countries.

Source:

Translation: ANF English