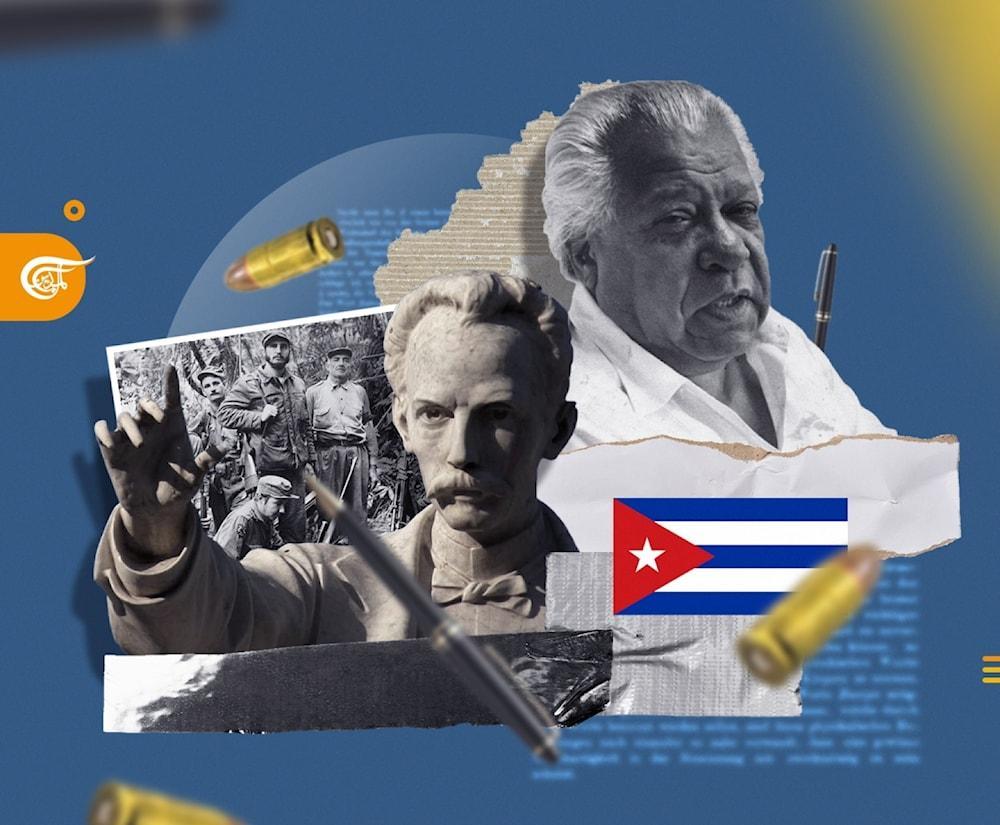

Cuba, a beacon of liberation from colonialism and a transgenerational icon of armed struggle, started its anti-imperialistic calling back when it stood with African nations suffering under colonialist rule all the way to its stance with Palestine in the face of its occupier.

Why was literature in this nation linked to the armed struggle in the face of invaders, with many of its scholars and writers turning to armed Resistance in the service of an uncompromising mission for sovereignty? Many well-established writers wrote their biographies with blood and art to be remembered generations later. The following are a few names whose works still enlighten the Cuban people and are still relevant decades later.

Anti-imperialism; a firm ideology

In January 1960, the first meeting of Latin American writers was held in Concepción, Chile. The meeting was attended by authors whose influence extended beyond South America, such as Ernesto Sábato and Nicanor Parra.

One of the conclusions of the meeting was that “literature should be considered, until further notice, more than just a cultural product or an artistic phenomenon. It is a tool for building Americana.” This concern stemmed from a larger battle between literary schools that had marked their presence and carved out their orientations in Latin America. It was also a collective message directed against the fascist political elite that was not interested in the rights of the people as much as it was in opening the doors to the looting of natural resources and subjugating entire peoples to serve an expansionist project based on brutal capitalism.

The Cuban Revolution was a central focus of these writers, who shed more light on a small island that the United States was trying to devour. Behind the US were Western ambitions that did not stop distorting the seen in Cuba. However, the path to liberation that Che Guevara’s comrades took in this country, and his journey with Fidel Castro from Beijing to the Soviet Union at that time, fascinated peoples who longed for freedom and inspired intellectuals to dare dream of a more just world. In this context, the travels made by intellectuals to Cuba must be noted, which include Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir.

After returning to France, Sartre said, “What should we do to contribute to the revolution in a better world? Just be Cuban.” Writer Susan Sontag was also not immune to the charm of the Cuban Revolution, and it was defended by José Saramago in the past.

Cuba, through its revolutionary image, managed to attract many writers who defended the revolutionary project intending to establish an authentic culture as intellectual individuals based on the Gramscian approach to this term, wherein he says: “It is them who sustain, modify and alter modes of thinking and behavior of the masses. They are purveyors of consciousness.” There were many renowned names among those writers who stood up for the revolution including Julio Cortázar, Carlos Fuente, and Gabriel García Márquez, as well as Eduardo Galeano, who acted as somewhat of a literary and media front to export Cuba’s culture and other Latin American countries as well as “third world” countries.

This literary force can be summed up by acknowledging that Fidel Castro made these icons consultants for the Cuban revolution in the areas of culture and arts, and their works served to promote them as bright stars in the political course of this nation for years. Their common language allowed them to serve as a bridge between the old world, built on consumption and imperial expansion, with Western-central values that promote the Western entitlement to control so-called fragile areas. These values represent nothing more than a void of margins used to besiege legitimate human ambitions to build intellectual and economic independence away from the stereotype of master and slave.

In her book, “Between the Pen and the Rifle”, Argentine researcher Claudia Gilman asks about Cuba and South America’s writers as follows: Must a revolutionary writer abandon his typewriter and learn how to use the mortar?

Gilman concludes that writers are committed to social and political causes to combat oppression in societies suffering greatly from injustice, and this commitment made changes to the perception of the intellectual who had become the equivalent of a Buddhist Monk, such as Camilo Torres, and intellectuals changed their civilian clothing to military fatigues in the guerilla warfare the majority of them engaged in against the oppressors in their respective countries.

José Martí: A Spaniard that championed Cuba’s independence

Fidel Castro did not attempt to convince those stunned by the Cuban revolution that he was a descendant of Karl Marx despite his support for the socialist bloc in the Cold War. However, he sought to convince everybody that he was a descendant of José Martí (1853-1895), who was a patriotic and national symbol of unity with the major Latin American nation, which had a place for every oppressed person in the world.

Martí was dubbed the “father of Cuban independence”, a journalist and political writer who founded the Cuban Revolutionary Party while exiled in New York in 1892. He is the author of the Manifesto of Montecristi, which was co-signed by the Dominican Republic’s General Máximo Gómez.

The manifesto declared the start of the Second War of Independence, which he dubbed “The Necessary War”. He also fought with his pen and his rifle until he was hailed as the Martyr of Cuba some of whose sayings were used to write the Cuban constitution.

One of his sayings that were immortalized in Cuba include: “Freedom is very expensive, and it’s necessary to either resign yourself to live without it or decide to purchase it for what it’s worth.” In many of his stances and writings, Martí saw that the only true power in the world was Love. Patriotism is love, and so is friendship.

Gabriela Mistral, a Nobel laureate in literature, says of José Martí: “The simple poetic texts are a true island of Martí’s poetic authenticity. They are the Martí essence that the enemy was unable to infiltrate. Therefore, this island is especially dear to me, and I find in it the greatest pleasure with the teacher, and I have my deepest conversations with him there.”

Raúl Gómez García: We are already in combat

On August 16, 1952, Alejandro, Castro’s nom de guerre, made it clear in an article in the Cuban newspaper Acción that “the moment is revolutionary, not political. Politics is the consecration of the opportunism of those who have the means and resources,” adding that “the revolution opens the way for the utilitarian merit of those who advance with bare chests carrying the banner of freedom in their hands.”

Among those who charged forward with reckless abandon was poet Raúl Gómez García (1928-1953), who was known as the Poet of the Centennial Generation and a fighter against the Batista regime. In honor of his martyrdom, Cuba celebrates Union Worker’s Day on December 14.

García’s speeches, correspondence, and poems represented a historical testimony of the events that took place during the armed struggle and documented the aspirations of a generation that believed that death and independence were on the same side. It is known that Castro read the latter’s vibrant statement after the rebels’ attack on the Moncada barracks.

His most famous poem in Cuba, entitled “We Are Already in Combat,” also embodied the need to respect the will of the Cuban people to liberate themselves and change the course of their history, and over time it became an inspiring anthem for later generations. The poem states:

“To defend the ideas of all those who died

To expel all the evil from the historical temple

Because of Maceo’s heroic gesture

For the beautiful memory of Martí

The turbulent destiny burns in our blood

From the generations that gave everything

Noisy dreams rise in our arms

All this shakes in the lofty soul of the Cuban

We are already in combat”

It is said that Raúl Gómez García was a descendant of the Cuban warriors who participated in the first 10-year war of independence during the 19th century. García was not only a teacher and law student, but he was also a painter and writer of fiery articles that never ceased to remind the reader that there is no need for theorizing, but rather that it is necessary to go directly to the fight, that is, to destroy the usurper of the people’s power. He emphasized the need to define one’s position on the revolution since it is also a tool for creativity because it is “something very noble.”

Nicolás Guillén and Cuban-African homogeny

Nicolás Guillén’s advocacy for the African ethnicity and its need to be integrated into the Cuban social fabric is evident in his poetic works. Despite their lyrical nature, they are tinged with a melancholy that depicts the agonies of slavery and the history of black people filled with servitude and journeys.

The works of the man who founded what is known as Black Poetry were able to express the documentary dimension of history through the collective experience. This experience is rooted in the search for the roots that had been buried by each new colonizer over four centuries, but they always resurface because they will never die.

Guillén’s blackness was also a state of mind through which he wrote about his ancestors, trying to paint a picture of a global civilization that includes all races. His texts were the culmination of a dreamy goal that affirms that the existence of Africans outside the bounds of Africa was possible and that his blackness was rich in features; it is Spanish, Caribbean, and Cuban. According to Jean-Marie Abanda Dengu in his book “From Blackness to Slavery,” it was more than just a stance, but an artistic and creative movement to re-evaluate the concept of civilization.

Nicolás Guillén was able to “rehabilitate” the Cuban-African race by transforming this concept into a revolutionary cultural tool. He allowed for the preservation of Afro-Cuban folklore by blacks on this island, making it one of the heritage pillars present in the collective consciousness of this society that defends respect for the individual particularities of the groups that blend within it through its tributaries coming from diverse countries.

The works of Guillén, who founded the “Society of Cuban-African Studies” and was considered a national poet since 1961, allowed Cuban blacks to showcase the musical richness that their tradition is based on. There is a lyricism in Guillén’s texts in addition to his political commitment. Some of his works include “Elegies,” “West Indies Ltd.,” and “The Dove of Popular Flight.”

José Zacarías Tallet: The revolution, an inexhaustible source of creativity

José Zacarías Tallet (1893-1989) lived through the premonitions of the Cuban Revolution. He began writing extensively in 1959 and left behind literary works, which are widely read and that have been compared to myths in terms of their strange and simple material.

He was known for his collection of poems “The Barren Seed,” as well as for his mixture of African and Cuban influences. Tallet won national awards, including an honorary doctorate from the University of Havana and the first National Prize for Literature. He always maintained that he was not a professional poet, yet he left his mark on the literary scene in his country.

Intellectuals in the face of imperialism

In a statement broadcast by Radio Havana on November 30 signed by the “Union of Cuban Writers and Artists,” they condemned what they described as a cultural attack on their country by the Hannah Arendt Foundation for the Arts.

They said that the aim of the foundation was to rewrite the history of the (Cuban) nation, which was facing continuous and increasing hostility from successive US administrations. They defended the right of the angry Cuban people to sovereignty and self-determination.

The statement goes on to say that the Hannah Arendt Foundation for the Arts is “trying to rewrite the history of the Cuban nation.” The statement says that the foundation is doing this by “funding projects that promote a negative image of Cuba.” The statement also says that the foundation is “trying to silence Cuban voices.”

The signatories at the time stressed that the Cuban people rejected falsification, saying there were US-backed foundations that had no place in Cuba to be broadcasting their materials, emphasizing their commitment to national artistic expressions.

souce: Al Mayadeen