The beautiful struggle of the “George Jackson in the Sun of Palestine” exhibition, which first opened in the West Bank in October of 2015, ultimately connected me with the African Palestinian community of the Old City of Jerusalem. That community would soon host the exhibit in their African Community Hall, a “stone’s throw” away from Al Aqsa Mosque (of which these Black folk are said to be the “guardians”). That event was held only a few weeks after our appearance at the 50th anniversary celebration of the Black Panther Party at the Oakland Museum of California. It is so fitting then that when we eventually managed to mount the exhibition in the Gaza Strip, two Augusts ago, despite the inhuman Israeli siege of settler-colonial occupation, this exhibition work is what introduced me to the Black community of Gaza. They came out — and their response was a thing of beauty too.

How did “Comrade George” get to Gaza? For several years, I had tried to get there physically myself. Before the coronavirus pandemic and global quarantine, I was preoccupied with this goal after having conducted many interviews with Palestinian ex-prisoners across the West Bank and additionally in Lebanon. Just when I thought there would be no way for me to get in, there was a message for me in Arabic on our Facebook page detailing the “George Jackson in the Sun of Palestine” exhibition. Before I had a chance to get the message translated, I received email in my university inbox from the same person: Muhammad Ismail. The brief note simply said, “I have information for you.” We linked up; we exchanged some precious historical details which will be made available in future publications; and, a little later, we plotted to bring the exhibition there to Gaza City in due time.

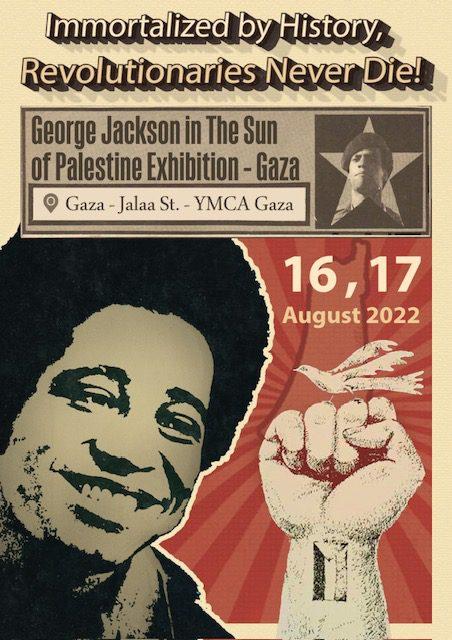

I worked with Muhammad and his younger brother, Ahmad Ismail, to make the event happen as a small collective unit. We were scheduled to open on Aug. 8, 2022. The original, beautiful poster artwork brilliantly designed by Ahmad indicates as much. But a day or so before this date, the Israelis bombed Gaza – again. Horrified, I could hardly be surprised. During my first visit to the West Bank, I heard that the Zionists refer to their rather ritual military attacks on Gaza as “mowing the lawn.” Both brothers agreed and insisted that it was essential to push forward again immediately. The second, edited exhibition poster announced the new date of Aug. 16-17, 2022. The extremely talented Ahmad would not need to change the date on that poster again.

A couple of weeks before the launch, an exciting preview article by Sabah Jalloul had appeared in Assafir Al-Arabi, a leading newspaper in Lebanon. Afterwards, Muhammad wrote an eyewitness report for media outlets such as Amad and Palestine News Network (PNN). He also gave a live interview-report on local radio station ZMN FM. PNN English could thus recount in “Gaza Celebrates George Jackson, International Revolutionary”:

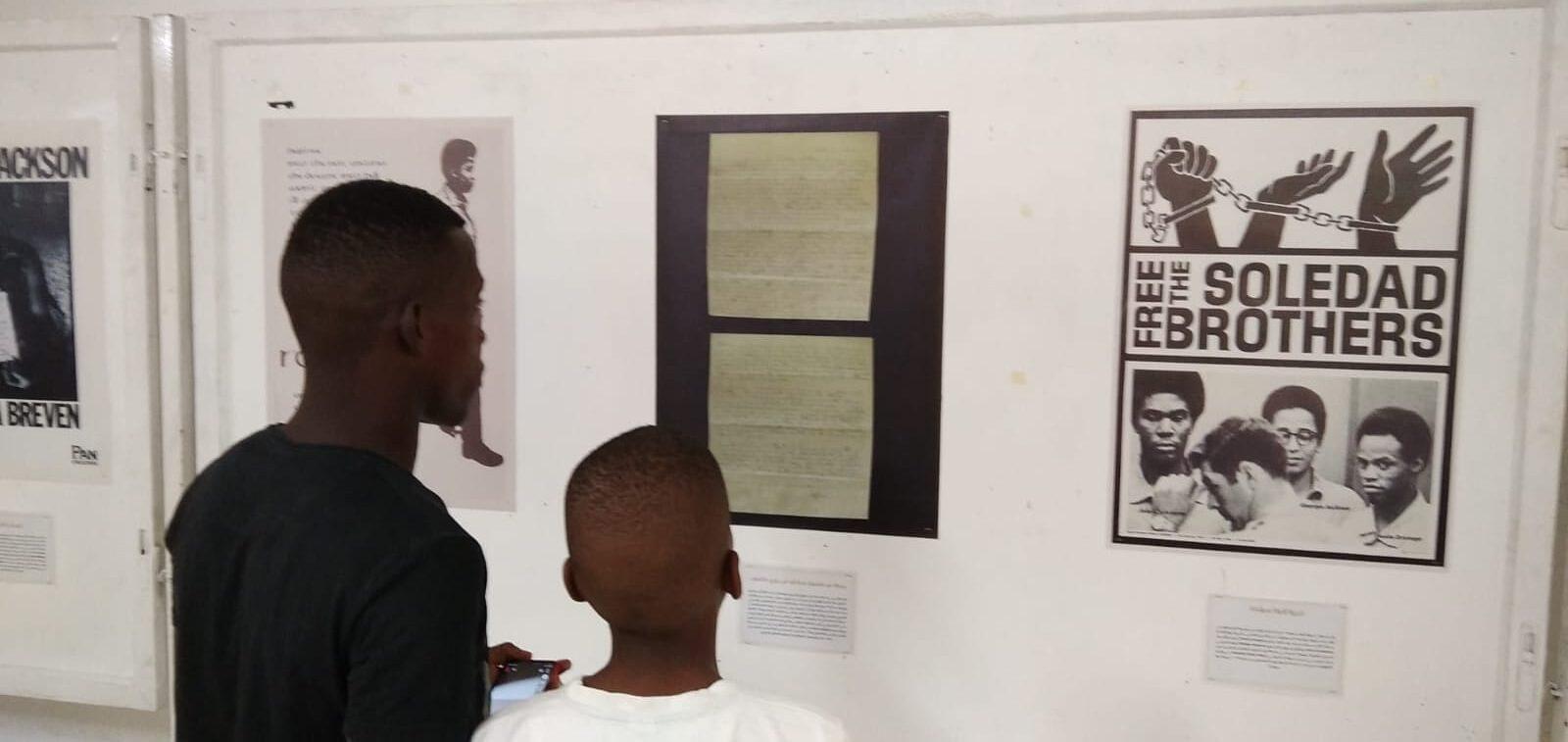

“Recently, in the middle of August, the YMCA-Gaza hosted the ‘George Jackson in the Sun of Palestine’ exhibition. The event came on the 51st anniversary of the martyrdom of the international revolutionary, George L. Jackson, the Black Panther Party Field Marshal who was assassinated by San Quentin prison officials of the U.S. government on August 21st, 1971…

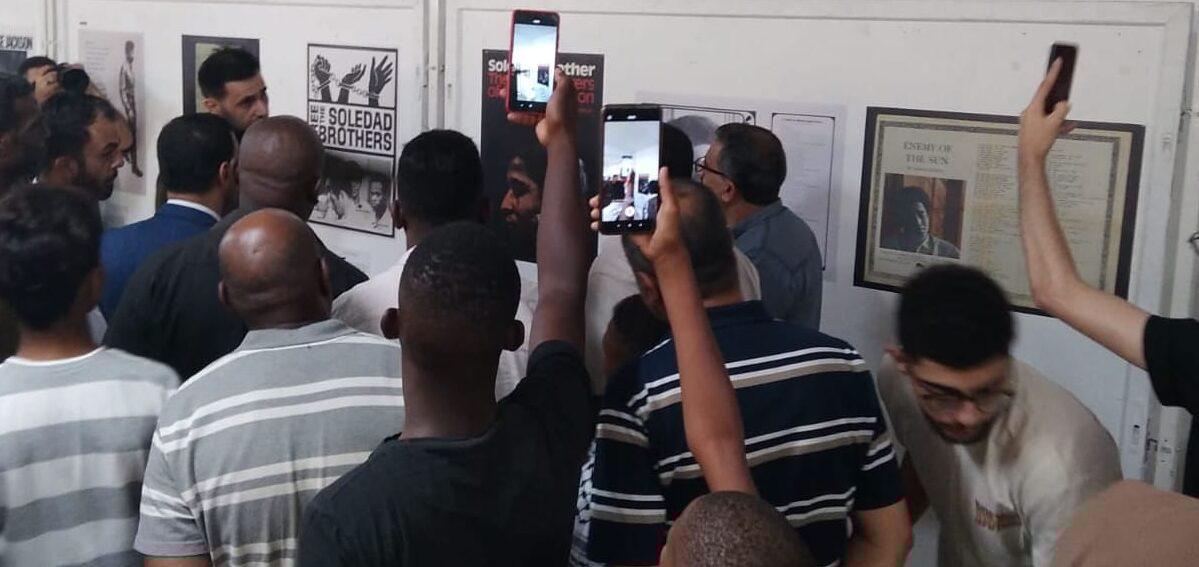

“This event was held over on two days: August 16th and 17th. Hundreds and hundreds of Gazan people came to witness the event, perhaps one thousand in total. This extraordinary number of attendees is especially impressive in light of the harsh circumstances the people of Gaza are now enduring after the last vicious Israeli attack on the Gaza Strip. That attack forced a postponement of the original exhibition opening from August 8th to August 16th.

“Attendance wasn’t only quantitatively but also qualitatively impressive. Besides a few members of the YMCA board of directors, a lot of writers, poets, literary critics, painters, historians, academics and teachers were present. Moreover, several retired Fedayeen visited as well – namely, Fedayeen of the Fahd Aswad (Black Panther cadres) in Gaza, Fedayeen of PFLP, and Fedayeen of Popular Struggle Front.

“Importantly, this was the first time such an event has been organized in Gaza. The exhibition initially opened in the West Bank and Jerusalem at the Abu Jihad Center on the Abu Dis campus of Al Quds University (on Oct. 20, 2015). It has traveled many places since then (such as Oakland, California; Vienna, Austria; Ghent, Belgium; Amman, Jordan, after moving across historic Palestine itself). It was last hosted by the African Community Center in the Old City of Jerusalem. A border-crossing exhibition, “George Jackson in the Sun of Palestine” was curated by Greg Thomas. The arrival of this “rebel expo” in Gaza was directed locally by author and independent scholar, Muhammad Jihad Ismail [https://english.pnn.ps/news/45529].”

I am thrilled to carry his “rebel expo” language forward! My own physical presence at the event came through a recorded video introduction of the exhibit, welcoming the people of Gaza to our postponed program. The overall success of this long-awaited effort was, in short, overwhelming.

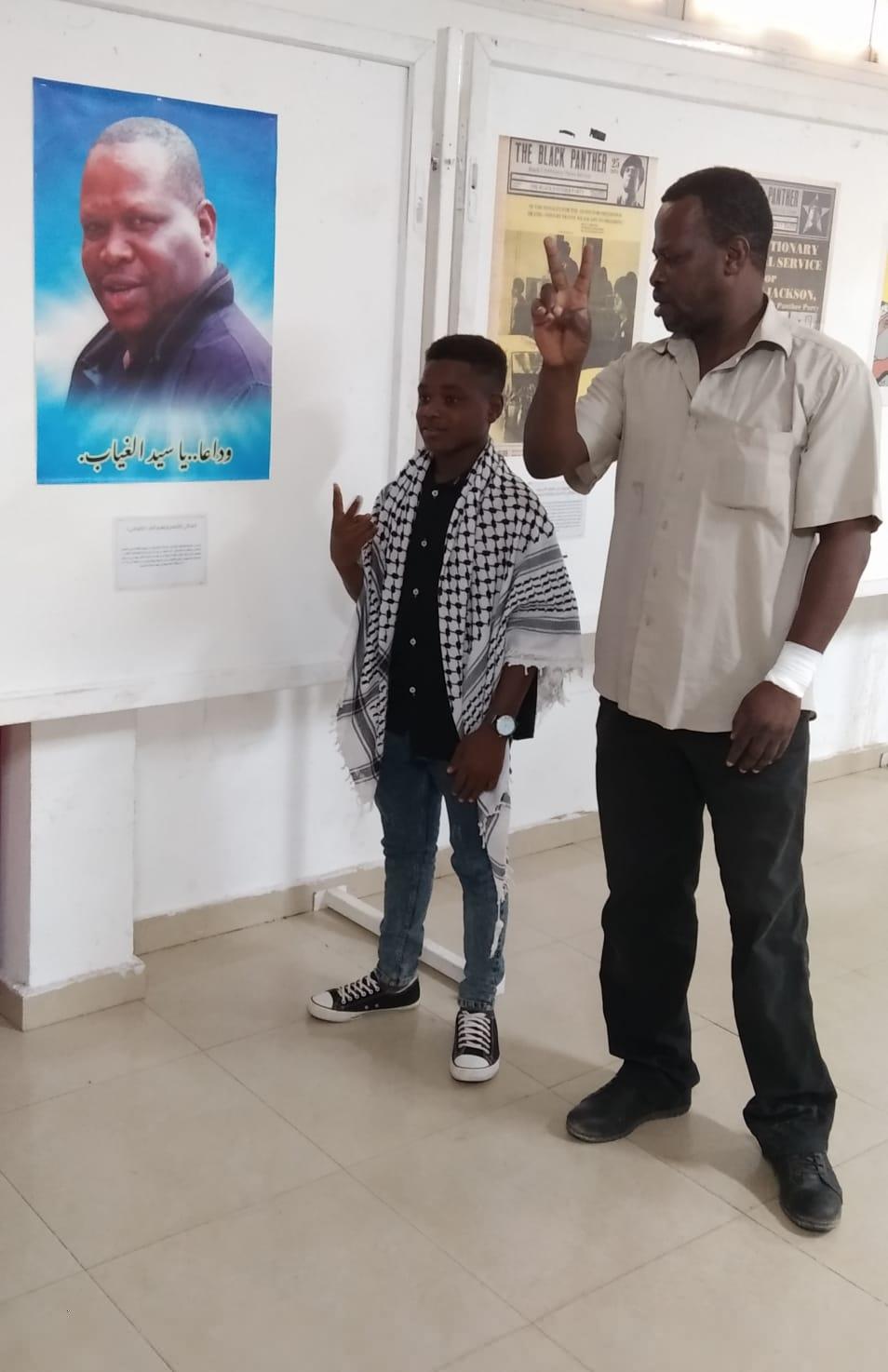

The Gaza Strip produced the largest number of attendees present at any version of this exhibition, anywhere, in all of its history. This was even anticipated in early discussions with my co-conspirators. What’s more, Muhammad had emphasized how monumental the Black community turnout should be without a doubt. For this must have been the greatest number of Black visitors ever, internationally speaking, further still. And, remarkably sensitive to the connections, they came to encourage a key addition to the exhibition: an image of the late Ibrahim Al-Er, an Afro-Palestinian who was an extraordinary legend of the First Intifada. Then, when it all came to a close, Muhammad told me that “[o]ne of the Black men promised me to put a photo of George in his home.”

The point of this project for me was always to conduct revolutionary research alongside exhibition programming. (This is what Frantz Fanon called a “passionate research,” as a matter of fact, in his classic book from the 1960s, “The Wretched of the Earth.”) From the outset, I wanted this work to connect local histories of captivity and resistance to the international story at the center of our traveling exhibit, which highlights the life of a genius Black Panther martyr and his stunning attachment to Samih Al-Qasim’s “resistance poetry” from Palestine. So, collaborating anew with Muhammad (who is an independent scholar himself), I began to conduct some major interviews in Gaza with revolutionaries and “resistance history” in mind.

We began this new work in 2023. It was gaining more and more success leading up to October – or “Operation Al Aqsa Flood” and the genocidal Israeli backlash. Yet at no point would this work just be stopped.

Besides other conversations with Black and Arab Palestinian political figures, one of these post-exhibition interviews was with a veteran Black leader and high-ranking Fateh party official in Gaza. He provides a historical outline explaining the origins of the African presence there. From his position, as both an intellectual leader and a political leader alike, he could sketch Black migration up from the African continent with ease. Some Africans came to Gaza escaping slavery elsewhere. Some arrived after the rise of Islam – pilgrimaging toward Saudi Araba via Egypt with Gaza on the way. Other Africans had come when performing their sub-pilgrimage to the Holy City of Jerusalem, as Afro-Palestinians still grounded in the Old City of Jerusalem routinely recount themselves. Some Africans also moved toward Gaza during the 18th century military campaign of Egypt’s Muhammed Ali. He sought to rule the Levant and put an end to the Ottoman Empire; and, reportedly, his army was “full of Black fighters.” Overall, most Black families currently in the Gaza Strip have been present for two to three centuries, according to this account, coming from all regions of the continent (in other words, northern, western, eastern and southern Africa). Lastly, it was estimated that up to 15 percent of the population of Gaza is Black or Afro-Palestinian, quiet as it’s kept.

The great Pan-Africanist filmmaker from Ethiopia, Haile Gerima himself, asked me to lead a recent event at his Sankofa store in the Black community of Washington, D.C., four months into this Israeli war on Gaza. He had long been wanting me to present some research on the subject of African-Palestinians there after my previous talk in their superb “How to Read” lecture series (for which my requested focus had been “Frantz Fanon with George L. Jackson”). Now I know that members of the Black community in Gaza dream of a Sankofa center of their own. When I shared the news of this latest invitation with Muhammad, he messaged me back: “Don’t forget to glorify the Martyrs of the George Jackson exhibit in Gaza.”

I was planning to do little else. So much had happened by then. The mass murder of the Palestinian people in Gaza (which is of course facilitated and funded by the U.S. settler empire under the Democratic Party president who had promoted its mass incarceration legislation for us in North America three decades prior) was felt on the most intimate level by me in the consequent loss of most of our comrades in the organizing work.

Young brother Ahmad Ismail was killed by the Israelis. A graphic designer, he had created the most stunning poster art while handling most of our technological concerns. The great warrior poet Saleem Al-Naffar had chanted his poems throughout the exhibition program, even helping to distribute invitations ahead of the exhibition opening. His entire household was killed by the Israelis in another airstrike. His son, Mustafa Al-Naffar, was a photographer and had contributed graphic design work, like Ahmad – such as the invitation cards and a welcoming banner at the YMCA entrance which read, “The George Jackson Exhibit Is the Exhibition of Martyrs.” Muhammad is currently the only local survivor of this historic exhibition team.

Still, unprompted, he soon offered a report on the status of Afro-Palestinians in the genocidally besieged Gaza Strip. A number of Black visitors to the exhibit had been killed as well: “Too many Afro-Palestinians were massacred in the ongoing genocide.” Where else will we get this news? One Black family in Bureij Camp was insisting upon living on the ruins of their bombarded home, refusing as a whole to flee or evacuate. Some video of them has appeared in online Arabic media: “We have no place of dignity and glory but this house,” said a member of this Abu-Breik family in images as overpowering as his words.

A discussion of mass graves and “so many Black families erased from existence” could turn to the Rawagh family. This big, notable Afro-Palestinian family in Gaza is certainly a family whom I wish I had learned about much earlier in an entirely different context. We could learn more about the concentration of Afro-Palestinians in Gazan cities such as Rafah and Deir El Balah and the life-and-death consequences of their location there amid Israeli assault campaigns. But their numbers are also great in battle. They are proud to be fighters in Palestine’s national liberation movement, the armed struggle. This is a common theme for Afro-Palestinians elsewhere, especially those organized in the Old City of Jerusalem such as Ali Jiddeh, the Qous family, Mahmoud Jiddeh, etc.

News of the Black community (and its very existence) today in Gaza makes a call which needs a response from us here and elsewhere in the Black world. The very concept of “diaspora” – as in “the African diaspora” – refers to a history of dispersion, scattering and disconnection as well as the politics of “divide and conquer.” We have fought to overcome this kind of separation-for-domination with movements of Pan-Africanism, “Black Power” and, most successfully, Marcus “Garveyism.” Indeed, our successes can be astonishing. It is interesting to me that Blacks and Palestinians have developed a specific approach to “solidarity” that understands the need for internal solidarity within the community before there can be possible solidarity with non-Black, non-Palestinian people outside or external to our communities.

The late UC Berkeley scholar Vévé Clarke gave us the concept of “diaspora literacy” as well. It is the ability to read Black cultural life beyond modern nation-state boundaries of the current world order. This literacy is something that we are always developing and expanding – against slavery, colonialism, imperialism, neo-colonialism and what George Jackson called “neo-slavery.” Black, African people are thus still finding each other all over the globe to this day.

How many of us are finding out about the Black community in the Gaza Strip for the first time now? (And what might it mean that many of us are only learning this now in the context of genocide?) Like all Palestinians, this part of our Black diasporic community needs our informed support. We hope to bring more stories and information about them as often as possible in the near future; and urgently needed financial donations of any amount can be made here to help with their daily life struggles in Gaza today:

Greg Thomas is a global Black Studies scholar and university-level educator from Southeast Washington, D.C. An author of several books, he has also curated traveling exhibits on George Jackson in Palestine as well as Kwame Ture a.k.a. Stokely Carmichael in Conakry, Guinea. He can be reached at elegba823@gmail.com.

Source: SF Bayview