I. Introduction

In the Western capitalist world, many stories remain untold, especially when they are connected to the African continent. A vivid example of this is Burkina Faso, a country that, despite its rich history and ongoing struggles against injustice and oppression, receives little attention. In this article, I aim to throw light on the often overlooked reality of Burkina Faso by tracing the country’s history up until the coup in 2022 and attempting to analyze the current political and economic conditions in the country.

In addition to analyzing the political conditions on the ground, I examined the impact of imperialism on the country. I aimed to create a deeper understanding of the challenges and struggles of the people in Burkina Faso and to emphasize the need for international solidarity and support in the fight against capitalist exploitation. It is time to tell the hidden stories of oppressed peoples and bring their struggles to the forefront of international attention.

II. History of the country

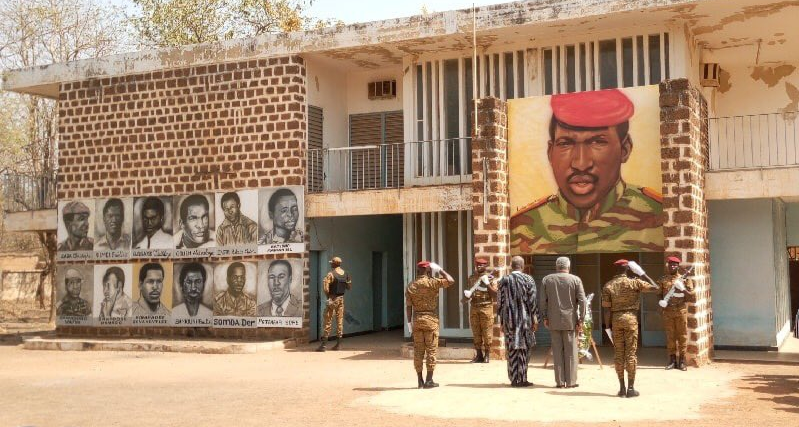

The history of Burkina Faso, located in the heart of West Africa, is a history of resistance, revolution, and struggle against imperialist oppression and colonial exploitation. It is a story that is strongly influenced by the figure of Thomas Sankara, a revolutionary who led the country in a time of profound change.

Burkina Faso, formerly Upper Volta, gained its independence from French colonial rule in 1960. The following two decades were characterized by political instability and repeated military coups. However, the turning point in the country’s history came in 1983, when Captain Thomas Sankara came to power in a coup carried out by his supporters.

Sankara, often referred to as the “Che Guevara of Africa,” was a staunch Marxist and Pan-Africanist. He campaigned for the liberation of the African continent from imperialist oppression and the self-determination of the African peoples. Under his leadership, Upper Volta was renamed Burkina Faso, which means “and of upright people” in the local languages Mossi and Djula – a symbolic act intended to reflect the country’s new revolutionary identity.

Sankara’s reign was characterized by radical reforms aimed at improving social and economic conditions in the country and ending the exploitation and oppression of the working class. He carried out extensive literacy and vaccination campaigns, promoted gender equality, fought corruption, and restricted the privileges of the political elite. At the same time, he nationalized land and natural resources and promoted local production and consumption in order to reduce dependence on imperialist nations.

However, Sankara was not only active at the national but also at the international level. He criticized the policies of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund and repeatedly called for a fairer world order. He denounced the debt burden of Third World countries and called for a collective refusal to repay debts in order to end exploitation by the imperialist powers.

Despite his popularity and achievements, Sankara was assassinated in 1987 in a coup led by Blaise Compaoré. Compaoré returned to neoliberal policies and ruled the country with a heavy hand for the next 27 years until he was finally overthrown by a popular uprising in 2014.

The exact circumstances of Sankara’s assassination remain unclear to this day. But his ideas, just like those of other revolutionaries, live on to this day.

After his death, the exploitation of the country continued. Burkina Faso became economically dependent on Western monopolies that plundered natural resources such as marble, gold, nickel, and phosphate.

This situation is typical of African nations that have been ruined by centuries of colonial exploitation, resulting in a weak economy and underdeveloped industry and, as a result, extreme poverty among the population.

The post-independence period was therefore fertile ground for the emergence of reactionary armed groups, which in most cases were used by the Western centers of power to protect their interests and continue plundering national resources.

It is estimated that more than 2 million people in Burkina Faso were dependent on food aid in 2021, mainly children, women, and the elderly.

III. Burkina Faso from 2022 until today

On January 24, 2022, the military took control under the leadership of Colonel Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba and deposed the previous president Roch Marc Christian Kaboré. In September of the same year, there was another change of power in which Damiba was deposed by the military under the leadership of Ibrahim Traoré.

These two coups, which were primarily justified by the growing terrorist threat in the country, marked the beginning of an exciting development in the country. After Traoré took power, Burkina Faso turned its back on the West and in particular the former colonial power France.

Since Traoré took power, Burkina Faso has made remarkable progress in various areas, although major challenges remain. In terms of security, the government has made considerable efforts to combat terrorism in the country, including increasing military spending, recruiting soldiers and 90,000 volunteers, and strengthening regional cooperation with Mali and Niger within the framework of the Sahel Alliance. These measures have led to partial successes, including the recapture of some areas, even if there are still many deaths from attacks.

Economically, the government has promoted agriculture, increased production through the use of improved seeds and fertilizers, developed irrigation systems, and promoted livestock farming. Infrastructure projects, including the construction of roads, bridges, and railroad lines and the improvement of the electricity supply, have been driven forward in order to increase the country’s attractiveness. The arrest of Vincent Dabilgou and four others for embezzlement and money laundering demonstrates the efforts of the specially established anti-corruption agency to combat corruption.

There is also a strong focus on economic independence, which is why a microcredit program for small businesses has been introduced and the development and opening of the first plant for processing waste products from mining has been implemented. The aim is not only to become more independent but also to shift value creation to the country itself. This effort was reaffirmed at the end of last year with the start of construction of the company’s first gold refinery.

Despite a still high poverty rate of 33% in 2023, there has been a decline compared to previous years (2022: 35%; 2021: over 35%). The government has increased social spending and the minimum wage and introduced a number of initiatives to improve the social situation, including scholarships for needy pupils and students, social programs for poor families, and development programs for rural areas. Investments were also made in the healthcare system: With an increase in the state budget, the construction of new hospitals and clinics, the subsidization and associated price reduction of medicines, and the improvement of the supply situation in rural areas were financed. In addition, the introduction of health insurance for all was begun and a vaccination campaign was launched to curb the spread of diseases such as malaria. The many efforts in the health sector have already brought initial improvements: Infant mortality has fallen and life expectancy has risen.

In the social sector, the government has decentralized political power and strengthened local authorities. At the same time, the participation of the population in political decision-making has been promoted.

Measures have also been taken to promote gender equality. These include increasing the number of women in political and economic positions, promoting the education of girls, promoting women’s cooperatives in the economy, awareness campaigns on women’s health, expanding prenatal care, and an awareness campaign on gender roles. Despite this progress, traditional role models and discrimination remain a major challenge.

IV. Analysis: Rule by the people or military dictatorship?

While the government under the leadership of Traoré is primarily portrayed in the West as a military dictatorship, there are exciting developments in the country that point to a progressive government.

Nevertheless, the ruling party in Burkina Faso, the “Mouvement patriotique pour la sauvegarde et la restauration” (MPSR), is difficult to categorize politically. It does not represent a clearly defined political ideology, although its statements and goals do indicate a certain tendency.

In the political compass, a well-known visualization of political ideologies, it would probably tend to be located toward the top left.

This is supported by its clear position on combating poverty and inequality, its proximity to trade unions and traditional left-wing forces, and its verbally unambiguous position against Western imperialism.

However, the perspective of a socialist society has not been discussed so far, which could raise legitimate doubts about the intentions of the political leadership. It must also be noted that the country is still in a state of emergency, which is characterized by domestic political insecurity. Furthermore, the MPSR is still a young movement that is still in its development phase. It is therefore possible that its political orientation will continue to change in the future.

Interim President Traoré’s rhetoric, on the other hand, sends out very clear signals.

Almost without exception, the 35-year-old head of state ends his speeches with the famous phrase “Fatherland or death!” (French: La patrie ou la mort), which was made famous by the Cuban revolutionary Fidel Castro, and stood like no other for the revolutionary socialist overthrow of the island.

In his first speech after the coup, he spoke of the need to refound the state, which is in line with the socialist idea of destroying the bourgeois state. He also sees himself as a campaigner for the decolonization of the country. At the Africa Summit in St. Petersburg, he compared the Soviet Union’s historical struggle against fascist Germany with his own struggle against French colonial rule and its remains.

“Why is resource-rich Africa still the poorest region in the world? We ask questions like these and get no answers. However, we have the opportunity to build new relationships that will help us create a better future for Burkina Faso,” he said, comparing imperialism to a modern form of slavery.

“But a slave who does not fight for his freedom is not worthy of indulgence. The leaders of African states must not behave like puppets in the hands of the imperialists. We must ensure that our countries are independent, including in terms of food, and that they can meet all the needs of their peoples themselves. Glory and respect to our people; victory to our people! Fatherland or death!,” he concluded his speech saying.

It, therefore, comes as no surprise that many observers have already drawn a comparison between Traoré and “Africa’s Che Guevara,” as Thomas Sankara was often called.

And his relations with the anti-imperialist states of South America also make this comparison seem logical.

He has already visited Venezuela and Nicaragua and emphasized the historical connections between the African and Latin American liberation struggles, again with reference to Fidel Castro and Cuba.

However, it is essential for the question of who is in control of the country to take a closer look at the ownership structures, which present a mixed picture. First the negative: the service sector employed 49% of all workers in 2021, of which almost 30% were employed in the financial system. The banking sector is one of the central economic pillars, but with the exception of “BSIC Burkina Faso”, the major banks are all privately owned, in some cases, even by large Western capital groups such as Société Générale.

In addition, the new government has always emphasized the importance of the private sector and works closely with the largest employers’ association in the country.

With this in mind, however, it must be emphasized that the capitalist class in Burkina Faso cannot be compared with that in Western nations. It is heavily dependent on foreign capitalists and does not have the dominant strength that we know from Europe, Asia, and North America.

And there are also positive developments that need to be highlighted: The industrial sector is dominated by state-owned enterprises and contributed to 32% of GDP in 2021, according to the World Bank. 25% of all employees are employed in these state-owned companies. The government also promotes the emergence of cooperatives in agriculture, trade, and handicrafts: it provides cooperatives with loans and other financial resources and offers technical support in developing their business activities. Control over mineral resources, which account for more than 80% of the country’s exports, is also in the hands of the state.

It is the mixture of a controlled private sector and a large state-owned key industry that is particularly comparable to Venezuela. An agreement between the Burkinabe and Venezuelan governments on mining cooperation, in which the Venezuelan minister promoted the Chavez-Maduro model, which places the state at the center of control over mineral resources, from exploration to processing and marketing, with particular attention to environmental protection, also fits in with this.

V. Conclusion

For this year, the transitional government had announced its intention to hold scheduled general elections. However, due to the ongoing difficult security situation, it is unlikely that there will be a smooth nationwide election.

One thing is certain: The transitional government is doing a lot to combat the consequences of colonization, which many former colonies are still suffering from today. It is taking a firm stand against the exploitation of the country by Western imperialists and is investing a lot of money to combat poverty in the country and improve the social situation.

As was the case in Venezuela under Chavez, a development is certainly taking place that will benefit large sections of the working class. In addition, the dominance of Western imperialism is being pushed back further, from which the entire international workers’ movement can benefit in the current situation.

The development must continue to be observed critically, but at the same time, it is a sign to the region that dependence on international capitalist exploiters is not an immutable law of nature, but a temporary state that can be broken. And this sign alone could encourage a development that will finally earn Traoré the title of “Che Guevara of Africa,” just as Sankara was allowed to bear it before him.

Julian Rivera

Al Mayadeen