The disagreements between the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) and the political power in Mexico have been constant. Since the 1994 uprising, the Zapatista position regarding elections has had three key moments.

Presidential elections are once again approaching in Mexico and, as every six years, more than one begins to question the Zapatista movement for its supposed “position” in the electoral process. But, what is the historical position of the Zapatista movement regarding the elections? We take up again three key moments to approach the position of the communities

1994. Elections and uprising

1994 was an electoral year. The six-year term of Carlos Salinas, who had come to the presidency of Mexico after a controversial presidential election in 1988, in which electoral fraud was key to the triumph of the PRI (Institutional Revolutionary Party), with almost 70 years in power, was coming to an end, and at the end of the year, the six-year term of Luis Donaldo Colosio, whom Salinas himself had designated as his successor, was scheduled to begin. In Chiapas, there would also be gubernatorial elections; Eltmar Setzer was in charge of the state, replacing Patrocinio González Garrido, a member of the Chiapas political elite who, just a year before, had been called by Salinas to be part of his government as Secretary of the Interior.

The irruption of the Zapatista armed movement shook the ground, and a lot. From the first moment, and there are the chronicles and interviews of journalists in the first days of January, the Zapatistas made it clear that the Salinas government was illegitimate and that legitimate elections were needed, in which different options could be chosen, with freedom and equality of opportunity for all and based on an electoral law that was not made at the whim of those in power. For this, they said, it was necessary for the Chambers of Deputies and Senators to ignore the Executive Power and the full cabinet and form a transitional government, and on that basis, call new elections.

When, after barely twelve days of war, Zapatistas and government sat face to face in the Cathedral Dialogues in San Cristobal de las Casas, among the 34 demands presented by the EZLN were those of free and democratic elections, the resignation of the head of the federal executive and the formation of a transitional government through elections monitored by the citizenry. The answers given by the government to the demands were discussed with the Zapatista rank and file after the dialogue ended, and they rejected them: they were mere white-washing and there was no guarantee that the necessary profound changes would be carried out. And the Zapatistas summoned civil society to a National Democratic Convention to discuss the course for the future, which was held in Zapatista territory at the beginning of August 1994. By then, in the tumultuous Mexican year, the nation’s aspiring president, Colosio, had been assassinated, and Ernesto Zedillo had taken over.

At the end of August, elections for President of Mexico and Governor of Chiapas were called, and for this position, as a candidate of civil society and with the support of the Zapatistas, Amado Avendaño, lawyer and journalist, director of a modest newspaper in San Cristóbal de las Casas called “Tiempo”, where the First Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle had been published for the first time, presented himself as a civil society candidate. His proposal was, following the Zapatista guidelines, to install a transitional government in the state, to call a Constituent Congress to elaborate a new Political Constitution for Chiapas and, once approved and enacted, to call elections with equal opportunities for political parties, social organizations and citizens in general.

Avendaño’s candidacy, who had to run under the banner of the PRD (Party of the Democratic Revolution) by legal requirement, awakened great enthusiasm among the civil society of Chiapas; so much so, that the powers of the State began to fear him enough to try to assassinate him: a little less than a month before the elections, and while he was on a campaign trip, his car was rammed by a trailer without license plates; three of his collaborators died and he was seriously wounded, though he ultimately survived. Even without him being present, the electoral campaign continued and in the elections, with a massive turnout at the polls, including in the Zapatista region, Amado Avendaño won by twice as many votes as the PRI candidate. The official party had tried by all means to prevent this from happening, with the “accident,” and with the numerous irregularities that occurred in the voting booths, and still not succeeding, the State Congress, which was supposed to ratify the election, declared Eduardo Robledo Rincón, candidate of the PRI, as the winner.

On December 8, 1994, at the same time that Robledo Rincón took over the governorship of Chiapas, Amado Avendaño was sworn in as Governor of Transition in Rebellion in the Central Plaza of Tuxtla Gutiérrez, the state capital. In a communiqué issued by the CCRI-CG of the EZLN two days earlier, the Zapatistas disavowed the PRI candidate, and recognized Avendaño as the constitutional governor of Chiapas whom they invited to head the popular government in rebellion in the state.

Once the democratic option through the electoral route was closed, the Zapatistas remained on the sidelines of these processes; the next elections were the municipal elections of October 1995 and in them, the Zapatistas and numerous civil society organizations, especially indigenous, did not vote. They awaited what would happen in the next attempt at dialogue with the State, the First San Andres Dialogue Table on Indigenous Rights and Culture, which began a few days later and ended with the signing of the San Andres Accords, which the Mexican government, headed by Ernesto Zedillo, refused to comply with despite having signed them. They have continued to do so to this day. From then on, the Zapatistas focused on building their autonomy and self-government.

The other campaign

At the end of Zedillo’s six-year term, the PRI lost the government of the country and the period of Vicente Fox began. The Zapatistas crossed the country in 2001, with the “March of the Color of the Earth” Their hope was that the San Andres Accords would now be fulfilled; however, the political class betrayed them and approved a law that did not comply with what had been agreed. The Zapatistas broke off all contact with the political parties, consolidated the Autonomous Municipalities and created the Good Government Councils and the Caracoles in 2003. With the end of Fox’s mandate, on July 2, 2006, Felipe Calderón, for the National Action Party (PAN), and Andrés Manuel López Obrador, for the Coalition for the Good of All, which was made up of the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD), the Labor Party (PT) and Convergence, faced off at the polls, with the former winning with only 0.56% of the votes.

But a year earlier, in June 2005, the EZLN released the Sixth Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle announcing that they would “walk all throughout the country, through the ruins left by the neoliberal war and through the resistances that, entrenched, flourish in it.” Their idea was to meet and bring together those who wanted to organize, to fight for democracy, freedom and justice, to build another politics, a program of national and leftist struggle and a new constitution. It is “The Other Campaign”, in which, first Delegate Zero (Subcomandante Marcos) and then several Comandantes and Comandantas, toured the country during 2006 and 2007, before and after the elections.

Although many said that the Zapatistas were calling for abstention, “betraying” López Obrador’s electoral movement, that was not the case: on multiple occasions, throughout their journey, the message was not “abstain”, but “get organized”:

“We tell them clearly: When the day comes that you have to vote, vote for the one you want. We do not tell them not to vote. What we tell them is that the solution is not up there. Up there are the political parties and we have seen them again and again, that there is no solution. What we have to do is to organize ourselves as peoples. Nowhere are we saying: “Leave your organizations and join a political party.” Nowhere are we saying: “Leave your struggle and do another struggle.” On the contrary, we are saying: “Don’t drop your organization. It doesn’t matter what size it is; keep it strong, resist, make it grow” and we only ask you: ‘Unite your struggle with other struggles and with other organizations.’ Amamaloya, Veracruz. 01/30/2006

This was and has always been the central nucleus of the Zapatista proposal: the problem is not voting or not voting, but how the transformation of society is conceived; voting alone is not a condition for change, and change will only come if we transform and make our own the mechanisms of participation and political control at all levels. As they indicated at the end of 2023, when they announced changes in their autonomy, the current pyramid of power has to be turned around in such a way that those of us at the top are the majority and those at the bottom govern by obeying.

This was, and has always been, the central core of the Zapatista proposal: the problem is not whether to vote or not to vote, but how the transformation of society is conceived; voting alone is not a condition for change, and change will only come if we transform and make our own the mechanisms of participation and political control at all levels. As they indicated at the end of 2023, when they announced changes in their autonomy, the current pyramid of power must be turned around in such a way that those of us at the top are the majority and those at the bottom govern by obeying.

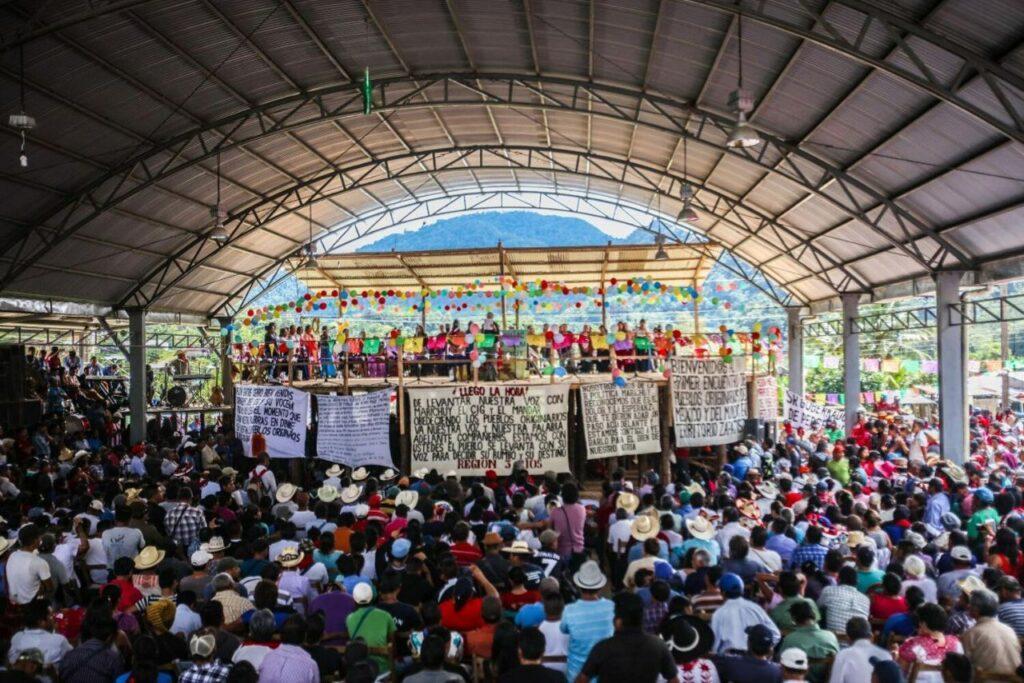

On October 14, 2016, in the context of the commemoration of the 20th anniversary of its inception and the fifth major gathering since its founding, the National Indigenous Congress (CNI), a historic ally of the Zapatista communities, declared itself in permanent assembly for internal consultation. Between October and December 2016, the indigenous peoples belonging to the CNI debated and reached consensus on a new political roadmap. On January 1, 2017, from Oventik, Zapatista territory, the CNI in conjunction with the EZLN shook the Mexican political chessboard with two announcements: the formation of an Indigenous Council of Government (CIG) for all rebel indigenous peoples in Mexico, and the entry into the 2018 electoral process through an independent candidacy materialized in the figure of the spokesperson of the CIG, the indigenous Nahua María de Jesús Patricio, Marichuy. The indigenous peoples gathered in the CNI thus presented us with an initiative of radical democracy with the formation of an indigenous self-government of national scope. The councilmen and councilwomen of the CNI would carry the word of the peoples from commanding obeying, and would be governed under the seven Zapatista principles.

They decided, as a tactic, to form an independent candidacy not to dispute power with the political class, but as a vehicle to travel the country and connect with the people, to create networks of organization below and to the left. The CNI would then seek to ‘hack’ politics, that is, using the technological metaphor, to break the limits of the Mexican political system, disable the circuits of traditional participation, and open a new path towards that other way of doing politics that had been sought since the Other Campaign. Once again, the indigenous peoples invited Mexican society to create those bridges to imagine and practice the three objectives of the Other Campaign. The months following this communiqué heralded the unanimous surprise of the political class, civil society and organizations in solidarity with the CNI and Zapatismo.

The mainstream media focused on the candidacy, obscuring the political discussion around the relevance of the CIG. More than one denounced a “new betrayal” of the Zapatistas by entering the electoral game and -once again- the disappearance of the indigenous rebel movement. Nevertheless, with difficulties, setbacks and mistakes, the CNI managed to open that crack, that path: it hacked the elections, first, by exposing the racism of the institutions and of the racist social mores towards indigenous peoples – “how is an Indian going to be president, let her start cleaning houses.”

The racism towards Marichuy and the socioeconomic and technological discrimination towards the CNI candidacy made it possible to expose the self-denied racism of Mexican society, which is now part of the country’s political conversation; and although the candidacy was not achieved, it did manage to weave those networks of struggle that keep the CNI and Zapatismo alive in the country and on the world stage of struggle. Thus, as they have been showing for decades, the rebellious indigenous peoples in Mexico have been exploring paths towards these new ways of doing politics, turning the usual practices upside down, making mistakes, but reinventing themselves along the way. And along the way, they are opening windows to what these new worlds could be, putting life at the center of the political chessboard, following their own calendar, and always looking to the future.

Original article by Lola Sepúlveda/ CEDOZ and Everardo Pérez / YRetiemble in El Salto on June 2nd, 2024.

Translation by Schools for Chiapas.