Chiapas, with its dense tropical jungle and imposing mountains, is a sanctuary of biodiversity and culture. This region, home to diverse indigenous peoples, is more than just a picturesque landscape; it is a bastion of resistance. For generations, its inhabitants have defended their land and their ways of life against threats of dispossession and exploitation. In every corner of Chiapas, nature and indigenous struggle intertwine, forming an unbreakable fabric of resistance and hope in the face of external pressures.

The struggle of these peoples for self-determination and the protection of their environment reflects a persistent resistance against the imposition of an economic model that privileges exploitation over conservation and respect for community life. However, the backbone of this current phase of capitalist development remains the destruction of communal land regimes. This is the story of the massacre of Las Abejas de Acteal in 1997, that of “the teacher” Galeano during an attack on the Zapatista autonomous project in 2014, or that of Samir Flores, in 2019, who fought against the expropriation of indigenous lands.

The spiral of violence born with paramilitarism, whose objective was to end the struggle of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) from the moment of its uprising, has deepened and become more complex. Armed groups are diversifying and their categorization has become increasingly difficult to define due to the opacity in which their actions take place. Today the war between drug cartels increases the brutality to which indigenous communities are subjected. Meanwhile, the State continues to be negligent if it is not a promoter or part of such violence. Its objective is clear: fragment the social fabric and facilitate access to land and resources for extractive, tourist and agro-industrial projects.

With 29 years behind them, the Civil Observation Brigades (BriCOs), organized by the Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Center for Human Rights (FrayBa), play a fundamental role in stopping the military and paramilitary violence imposed by the State in the territory. With this initiative, since 1995, thousands of people from all over the world – mainly from Europe – have participated in this mechanism to counterbalance the violence exercised against people; the brigade members break the siege of misinformation, document first-hand and deter attacks. And it has not been easy, particularly in recent years where the supposed leftist government of MORENA, through its leader Lopez Obrador, has fiercely attacked the work of Human Rights centers in Mexico.

The Mexican president has continually denounced FrayBa as a conservative NGO, spreading hoaxes about the situation in the Mexican southeast, and “against the social change” that he represents. And not only to FrayBa, but to any person or organization that has reported an abuse of human rights. A recent example is that of June 20th this year, when the president attacked the Agustin Pro Human Rights Center, asserting that, in relation to the Ayotzinapa case, he had evidence that said Center “signed a hidden agreement with the former President Peña Nieto behind the families [of the 43 missing normal students] and promoted protections so that dozens of those involved in the disappearance would be released…”, and that, “there are interests from foreign agencies to blame the Army for that tragedy.”

The BriCOs have been and are a mechanism by which international presence is guaranteed in communities threatened by military and paramilitary violence. They have been and are an instrument to fight against the impunity of state or parastate bodies and contribute to reducing the repression suffered by indigenous communities. They have been and are a strategy of citizen participation in defense of human rights and internationalist solidarity. They have been and are a mechanism to protect and safeguard the physical integrity of indigenous communities that fight every day for a world in which many worlds fit. They are and always will be, in short, a counterweight to violence.

Observers of different nationalities gather in the camps throughout the year, collect stories, testimonies and share various forms of struggle. Because common rights go hand in hand with the construction of new realities, new strategies, new alliances and new models of social organization. Among many other people, these are the memories of brigade members in the La Realidad and Acteal communities, who started from groups such as Lumaltik Herriak in Euskal Herria and Nodo Solidale in Italy, and lived together over time in various parts of Chiapas.

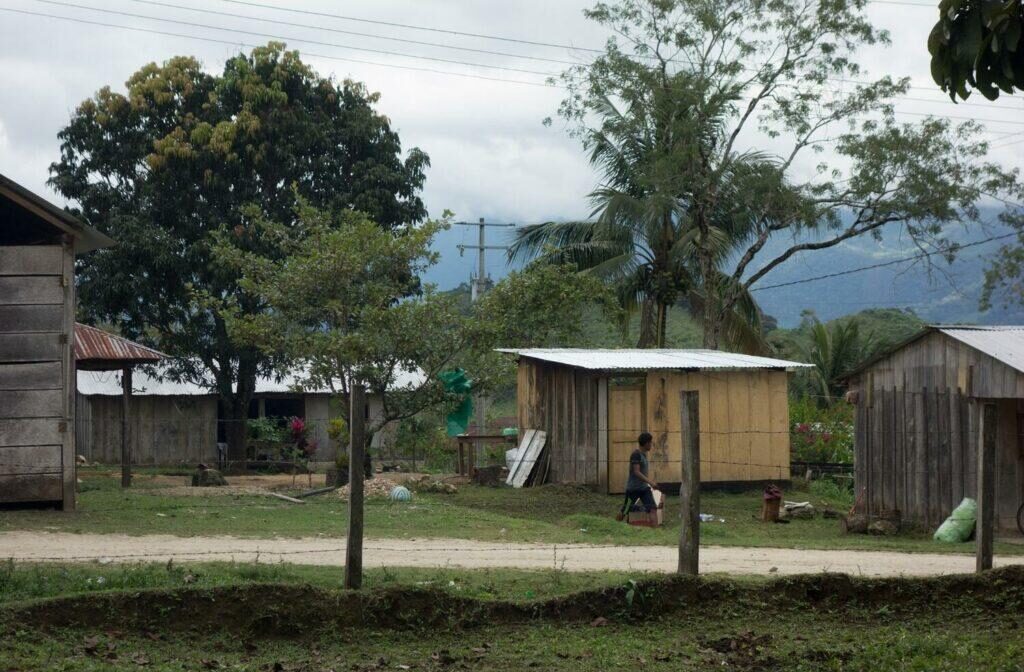

La Realidad, Lacandon Jungle

In the Lacandon Jungle, amidst threats of dispossession and exploitation, reside projects of Zapatista resistance and autonomy. The population of La Realidad is home to what was the first Aguascalientes, now a Caracol, a center of political and social organization that reaffirms the self-determination of the communities. In this very symbolic Caracol, the closing of the First Intercontinental Meeting for Humanity and against Neoliberalism took place in 1996. A river divides the community in two. On one side stands the Zapatista School, on the other, the observers’ camp. On the main road there is an iron sign where you can read “With us, we Zapatistas, compañero Samir Flores Soberanes of the CNI lives.”

Samir opposed a hydroelectric plant that the government was going to launch on land owned by the National Indigenous Congress. One Wednesday morning they shot him in the head in Morelos, in the patio of his house. The same fate befell Galeano, a teacher at the Zapatista School of La Realidad, who was also murdered in his town during an attack on the Caracol. After the teacher’s death, his companions remembered his words: “we Zapatistas do not depend on the bad system, but we build our own system of government.”

That May 2nd, 2014, they took the lifeless body to the Junta where his son cried for him among other inhabitants of the community. The then minor addressed the members of the paramilitary force, inhabitants of the same town and responsible for the shooting in the town, “justice without revenge or deaths,” he told them. He was aware that the Zapatistas were not like the paramilitaries of La Realidad, bought by the projects of the “bad government.” “We are going to use our anger against the capitalist system.”

A few years later, Galeano’s son got together with two other companions every night to rehearse under the Escuelita with the company of his three guitars. By the light of a candle they set the scene for the night in the community and it is always a joy for the brigade members who listen attentively to them from the other side of the river. They are the Southern Hummingbirds (Colibríes del Sur) that sing of the fallen fighters and hope.

Let us remember this story of freedom

Of fallen guerrillas who are not here today

Long live the resistance and those wounded in combat

They gave us their lives to see this people free

Stories of Freedom, Southern Hummingbirds

Acteal, Chiapas Highlands

The community of Acteal, where Las Abejas organization resides, has existed since 1992, before the EZLN insurrection, and is one of the many demonstrations of the strength of the indigenous peoples, in this case Tsotsil Maya, in the conquest of self-determination. A community that carries with it the pain and strength of the memory of bereavement: the Acteal massacre on December 22nd, 1997.

27 years have passed since the paramilitaries murdered 45 residents of the community, most of them children and women; however, to this day, time still does not heal their wounds. Because the strategy of the Mexican State to combat the EZLN and the multifaceted forms of indigenous struggle has always been, and is, to pay for violence and direct it against those who propose an alternative and a dignified life.

The Mexican State does not listen to the demands of the indigenous peoples, kills dissidence and buries it in the desert or in the mountains of the South. That was and is the destiny of the communities of the Chiapas Highlands. And that was also the fate that took – directly or indirectly – a girl some months after being born in the community a few years ago.

It was five in the morning, the brigade’s last day. A child knocked on our door and a father, only 27 years old, was crying for his 11-month-old daughter who had just died from a disease that was easily treatable with medication. But in southern Mexico, in indigenous territory, there is no easy cure.

Well, it is difficult to explain and reason about time in those moments. When two of her classmates refused to accept the death of the little girl and put a mirror under her nose to see if she was breathing. She was breathing, she was still breathing! “Hurry up” the people shouted. “Call the health promoter in the Zapatista neighborhood, tell him to come, it’s important. Call a taxi, we can rush to San Cristóbal, we can do it, we need to get to the hospital.”

But then time ceased to exist. Time had no mercy for María Angélica, it had no mercy for her family and it had no mercy for the entire community that had been awake since five in the morning crying and hoping that there was a God who would not allow a girl to die a few months after born. But time is not an entity, it is not God, nor does it have morals.

Time was here before us and it will be here after. Perhaps in those hours I understood how they perceive time in the mountains of Chiapas. But that is not something that can be described in words.

Acteal, Elia Bedoni

Understanding the life of an indigenous community is not a job of years, but of a lifetime. Being close to them you can appreciate that absence of madness that we Europeans experience every day. You can try to get closer to that feeling of freedom that we know as a slogan, but which in reality is nothing more than a plaque that hangs on the cell wall. As long as capitalism exists, freedom will not be known. For anyone forced to live within its fluid confines.

Original article by Elia Bedoni and Ana Onraita Larrea at El Salto, June 23rd, 2024

Translated by Schools for Chiapas