Compañerxs, it’s been a while. Much has happened since we last wrote, what with the elections and related violence in Mexico, and the confounding policies of our own government here in the US.

While we might be remiss not to acknowledge the election of Claudia Sheinbaum, the first woman and climate scientist to the office of the President of the Republic, as a significant moment, we would also be remiss to assume this implies a major shift on the topics indigenous rights and culture, human rights, or the health and safety of the human and other-than-human inhabitants of the territories. Ironically, her election may mean very little for either humanitarian or environmental concerns.

The finer points of the political “transition” will begin to reveal themselves down the line, but control over routes and resources (the how and the what of accumulation by dispossession) in the Mexican southeast will continue to be disputed, and this will continue to impact the communities who are always on the front lines — the indigenous communities.

However, even as Chiapas falls between militarized zones of interest and heavily-armed players of capital, indigenous communities continue to build the infrastructure for life and dignity.

And with that, we want to share this little ray of inspiration, and ask for your help.

Early on last year, a compa from San Cristóbal told us about a community who had “lost” their school nearly 8 years prior, due to the incidence of organized crime and insecurity in the area. Their children, during that time, had not learned to read and write, and they were looking for a teacher.

Of course, our name would signify that we were in the “business” of schools and education and such. Over its 30-year history, Schools for Chiapas has been involved in various aspects of education, and has built schools throughout the autonomous territories. But the classrooms and teaching have always belonged to the communities themselves, and with our background in autonomy according to the Zapatistas, we knew that any long-term solution in education must also.

So we met with representatives from the community, and after holding community assemblies and discussing amongst themselves, they came to us with a plan to train and support community education promoters. On our end, we began coordinating with an extraordinary Tsotsil educator, Miria, to accompany them in their journey.

Education is something sacred, and we do not take lightly the opportunity to support this space of vital formation that we consider to be a foundation of autonomy. Particularly in these communities, this space serves to strengthen identity and relationships within the human and also with the other-than-human worlds. That said, autonomy is just that. It is up to the community to collectively decide how to make it work, how much energy they have to put into education given that they work six days a week.

Finally one Sunday morning in January, it was time for the first “diagnostic” workshop, to assess the capacities of the promoters-in-training, and the strengths of the community as a whole. We met at Sendas, and drove to where three of the men awaited our arrival. As we climbed the hill to the little chapel where the session would be held, it seemed the whole community was there to greet us.

That day nearly every father in the community was in the room, a few younger women and one elder, as well as children ranging from 3 to 13, every one of them so eager to learn how to serve their community as education promoters. We listened as Miria led the session in Tsotsil, their mother tongue, catching the periodic transition words in Spanish, but mostly just watching the faces. Miria read “The Giving Tree” by Shel Silverstein in Spanish and asked the promoters to comment on their reflections. While the story touches themes that are universally human, the interpretations were beautifully unique.

Later, thanking us, one father commented what a surprise it had been to have a teacher who spoke their language, and how much it made them feel at home. We feel that school should always feel that way.

Over the next 5 months, Miria met every Sunday with this group who were to become the new education promoters. They learned games and activities to improve fine motor skills and pattern recognition, vowel sounds and comprehension. At that point they decided that it was time to put these skills into practice, for the promoters to start working with the children themselves.

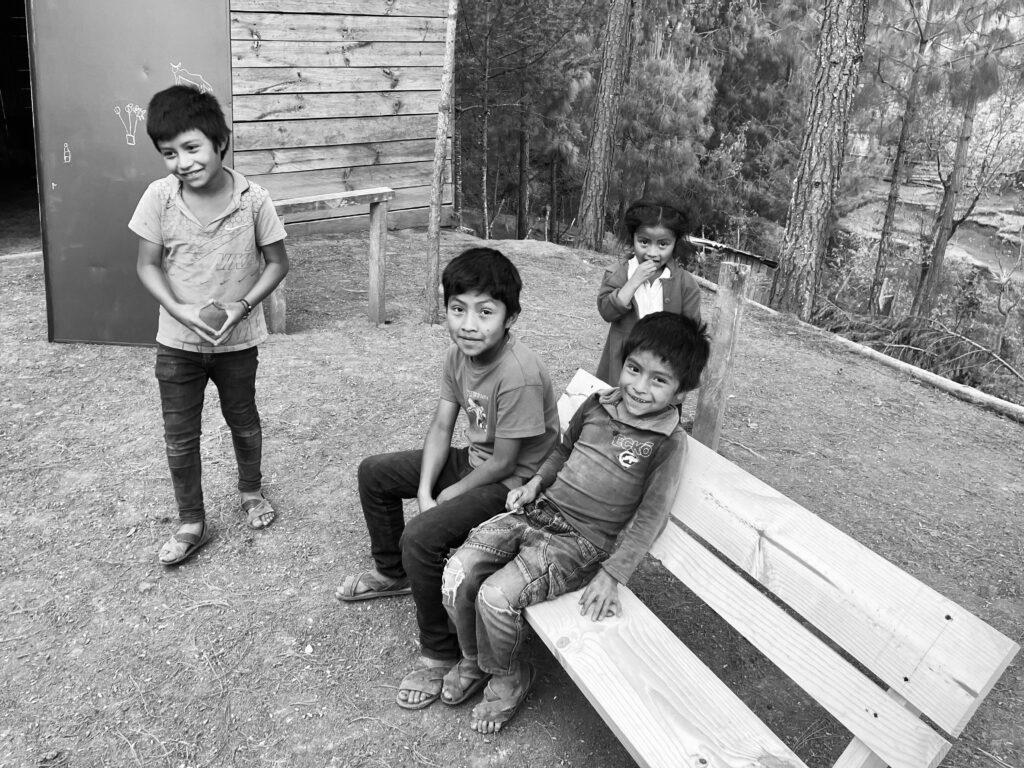

What began as literacy and reading comprehension is now evolving into other areas of education, and the promoters meet bi-monthly with Miria to develop new material, bringing questions from their recent experience. Their numbers have not waned and neither has their thirst for learning. The men have built beautiful benches and desks for the students, and the time has come for the school to have a home of its own.

We want to help this community build a place for their desks and their books and their chalkboards and their classes.

And with your help and a generous matching offer for all the funds donated, we can do that – it takes a village!

Liberatory education, preventive health through traditional knowledge of medicinal plants, campesino and solidarity economies through local networks, and mutual aid are all components of lekil kuxlejal (the Tsotsil concept of collective “good living” or a life in balance with all things.) And as far as we can tell, be it in Chiapas or anywhere else, these areas of work are at the heart of community well-being.

Due to the prevalence of organized crime throughout the state and widespread insecurity, the schools are often the first casualty. But armed with pedagogical training, inspiration and a small amount of support for materials, families in an organized community have the foundation for sustained education autonomy.

In these autonomous schools, curriculum from literacy to mathematics is rooted in their own language and in the world as they see it. Questions and materials arise from lived experience, as opposed to State-imposed textbooks. History starts with one’s own place in the world. Science starts with observations in one’s own milpa.

From that line of thinking, the problems we need to solve do not get solved from above, but from below and to the left. Our solutions come from our collective efforts within. This is how we transform our relationships, society and the world.

Thank you, always, for all that you do.

Donate now to have your gift matched!

Source: Schools For Chiapas