The history of Chiapas is unique; there the most conservative elites of the region who were at the forefront of the Mexican revolution, so when it ended, they retained all political and economic power, which gave the state special characteristics; at the end of the 1940s, the Lacandon Jungle was practically uninhabited; only a group of Carib Indians known as Lacandones lived there, but they had nothing to do with the original Lacandones who lived in Chiapas at the time of the conquest and who were exterminated. On the margins of the jungle there was a strip of land where the most important farms in the area were located; it was the so-called “franja finquera” where, under the iron rule of their owners, indigenous laborers lived and worked in conditions of semi-slavery.

Since the beginning of the Agrarian Reform promoted by President Lázaro Cárdenas in the 1940s, many of these peons decided to claim land, and so that these petitions would affect the interests of the landowners as little as possible, both the state and federal governments encouraged the petitioners, mostly Mayan Indians, to move into what they called “national lands,” that is, into the interior of the Lacandon Jungle. And so, starting in the 1940s, the canyons of Ocosingo and Las Margaritas were settled, the northern part of the jungle in the 1950s, the deepest part of the jungle, bordering Guatemala, in the 1960s, and finally, starting in the 1970s, the southernmost part, in Marqués de Comillas.

Adding to the problems of settling a practically uninhabited territory in which there were not even good roads, was that on March 6, 1972, President Luis Echeverría published a decree granting 614, 325 hectares of land to 66 Lacandon families, recognizing them as the true and only owners of the jungle; this decree affected a territory that was already inhabited by other indigenous people who, encouraged by the government, had chosen those “national lands” to settle in and who were either in the midst of filing their agrarian cases, or even already had a presidential resolution in their favor, and who with the decree were left in a legal limbo, since all the above was unknown and those lands became the property of the Lacandons. A new problem arose in 1978, when the Montes Azules Biosphere Reserve was established in part of the Lacandon Decree territory. In order to fight against all these problems, to obtain new land allocations, to create new communication routes and improve existing ones, and to achieve minimum levels of education and health, the peoples and communities created important peasant organizations to fight for their rights.

One day in November 1983, six people arrived in this place, one woman and five men, three of them indigenous, with a mission: to create a guerrilla group that would settle in the region and from there, spread throughout the country, make the revolution and lead Mexico towards socialism. The political background of these six people was in an organization called National Liberation Forces (FLN), founded in 1969 in the city of Monterrey; there were several occasions in which the FLN tried to settle in Chiapas, although only the first one had some success, in 1974, but only for a short time since they were discovered by the army and their members were killed or disappeared. Years later, a group arrived in San Cristóbal de las Casas and made contact with some indigenous people, leaders of the different peasant organizations, laying a minimal foundation so that the founding group of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation could arrive in Chiapas, settle in an area where the indigenous people had family contacts and found the EZLN. During the first years they hardly had contact with the population since their mission was to acclimatize and get to know the terrain, but little by little they began to make contact with the communities in the area; new members joined the group, while some of the first ones to arrive returned to the cities with other jobs; the EZLN began to grow.

In addition to the difficulties of life in the jungle, the problems derived from the Lacandón Decree and the Montes Azules Reserve, the repression exercised by the state governments, always with federal support, allied with the landowners, with special mention of governors Juan Sabines (1979-1982), Absalón Castellanos (1982-1988) and Patrocinio González Blanco (1988-1993), and the urgent need for land endowment, in the early 1990s, an even more serious problem was presented: Mexico’s president, Carlos Salinas de Gortari, who had become president in 1988, under serious suspicion of fraud, began to negotiate the Free Trade Agreement with the United States and Canada, an agreement that, according to the Mexican government, would bring Mexico into the “first world”. One of the conditions imposed by the United States in this negotiation was the guarantee of access to land for its large agribusiness corporations, which meant a radical change in Article 27 of the Mexican Constitution, which since the time of the Revolution, protected the land of the peoples and communities in such a way that it, among other things, could not be bought, sold or seized. With the change, not only could everything now be done freely, but also in order to give “legal security” in the possession of the land, Salinas decreed the end of the Agrarian Reform and with it the end of the hopes for a better future for many peoples.

It was at this point that many communities in Chiapas saw the EZLN as their only hope for the future and began to join the organization on a massive scale, which not only meant an immense strength for the organization but also an internal revolution: the communities “appropriated” the EZLN and the organization completely changed its conception of guerrilla warfare and ceased to be a “foquista1” group, in the image of Che Guevara’s guerrilla movement, and its fundamental base became the communities. And many of these, by 1992, were thinking that they had no other way out than war. In spite of the fact that the situation was not favorable – the Berlin Wall had fallen and along with it, also the so-called “socialist camp” and the guerrilla option was so unpromising that the guerrillas that had proliferated throughout the continent decades before, for the most part no longer existed or were negotiating their incorporation into civilian life, as happened in Guatemala and El Salvador – the communities reflected on their lives and their future and voted in the majority to go to war. Once they decided to go to war, they gave themselves a year to prepare.

The first public appearance of the Zapatistas, although no one knew it was them, took place during the celebration of October 12, 1992, when a contingent participating in the demonstration in the city of San Cristobal de las Casas, deviated from the planned itinerary and knocked down the statue of Diego de Mazariegos, the conquistador of the region, which was in a central plaza of the city.

The Zapatista Irruption: Fire and Words

On December 31, 1993, the President of Mexico, Carlos Salinas de Gortari, held a big party at his official residence in Los Pinos to celebrate the beginning of the new year and, most especially, the entry into force of the Free Trade Agreement which, according to official propaganda, was the confirmation that the country was joining the club of the most advanced economies, the highest standards of living, the best technology and a great political influence over the rest of the nations; It was the crowning achievement of a six-year term that had started off on the wrong foot with the suspicion of fraud and that in his last presidential year had high acceptance values among the population, a presidential candidate who was in tune with him and plans for the future, which included leading the World Trade Organization (WTO) when he handed over the presidential sash to his friend Luis Donaldo Colosio, after the presidential elections of August 1994. In the middle of the party, in the early hours of the morning, a military man entered the room and said something to Salinas that no one could hear; the president then left the room and never returned… No one knew what had happened, but soon alarming rumors began to spread of an armed uprising in the southeast of the country and before long, the party was over.

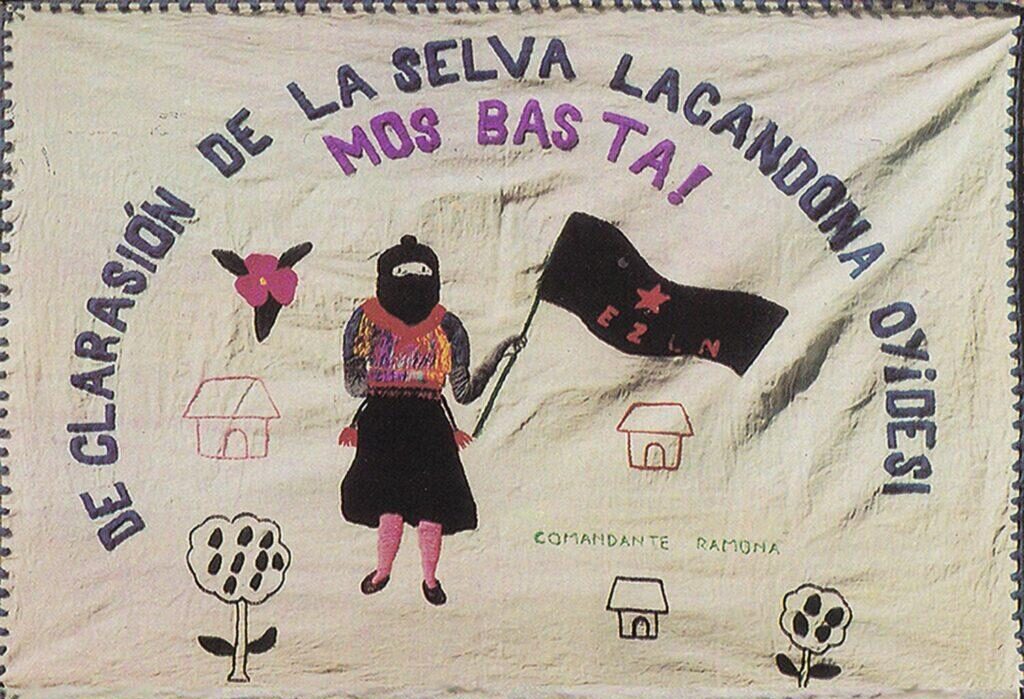

Meanwhile, in Chiapas, the four columns of Zapatista troops had set the order to begin the war for 24 hours on December 31; one column left from the jungle, advancing on Ocosingo and taking several farms along the way, before taking the city; another took the municipal capital of Altamirano where part of it remained as a checkpoint, while another advanced and took the cities of Chanal, Oxchuc and Huixtán; A third column left from Los Altos de Chiapas and took San Cristóbal de las Casas, where, from the balcony of the municipal palace, the First Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle was read, which a few hours later was spread throughout Mexico and the world; finally, a fourth column took the municipal seat of Las Margaritas.

In total, seven municipal capitals were taken: San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Altamirano, Las Margaritas, Ocosingo, Oxchuc, Huixtán and Chanal. In spite of the little resistance from the State security forces, who were also celebrating the beginning of the year, there were casualties; the EZLN has recognized that on the part of the federal forces there were at least 27 dead and 40 wounded and that they had 46 fallen in combat, among them Subcomandante Insurgente Pedro, head of the Zapatista General Staff and second in command of the EZLN, who fell in Las Margaritas, and Comandante Hugo, Francisco Gómez, fallen in Ocosingo.

Except in the latter place, where the confrontations with the federal army lasted until the 3rd, the order was to withdraw on the 2nd, so that any clashes that might occur would be in the mountains, well known terrain for the insurgents. In this retreat from Las Margaritas, the Zapatistas passed by a hacienda owned by the former governor and major general Absalón Castellanos Domínguez, member of one of the most influential families in the region; the general was in the house and was taken prisoner of war by the Zapatistas.

While the war continued, with the Mexican Army bombing civilian populations around San Cristóbal de las Casas, Mexican civil society immediately mobilized to demand a cease-fire from the parties. This finally took place on January 12, 1994, after a massive demonstration in Mexico City and in the main cities of the country, which was also reflected in many other cities in Europe and the American continent.

From that moment on, everything went very fast: Salinas appointed a Commissioner for Peace who contacted the Zapatistas through the mediation of the Bishop of San Cristóbal de las Casas, Samuel Ruiz and at the end of February, a few days after the prisoner of war, Absalón Castellanos, was handed over to the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) after a Popular Trial headed by a Zapatista military tribunal, which condemned him to live “until the last of his days with the sorrow and shame of having received the pardon and kindness of those whom he so long humiliated, kidnapped, stripped, robbed and murdered,”a delegation of the EZLN arrived at the Cathedral of San Cristobal, renamed the “Cathedral of Peace,” and initiated a dialogue with the government to put an end to the conflict.

It is not only the first time that the Zapatistas have met face to face with the government; it is also the first time that they have had contact with civil society, which decided to assume a protective role and set up a security cordon around the Cathedral for the duration of the dialogue. In this dialogue, the Zapatistas presented a series of demands covering problems specific to Chiapas, but also to the whole country, while the government tried to reduce the problem to purely local issues. The talks lasted ten days, and although the government wanted a quick signature, the Zapatistas said that peace would have to be decided in the same way the war was decided, through a consultation with their bases; while this was taking place, the presidential candidate for the PRI, Luis Donaldo Colosio, was assassinated, which was interpreted by the EZLN as a sign of war and interrupted the consultation for a while, declaring a Red Alert. When the consultation ended, the majority was against accepting the government’s proposals, which were clearly insufficient.

The Zapatistas issued the Second Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle in which they called for a National Democratic Convention, in the first days of August, with the objective of “organizing civil expression and the defense of the popular will.” In the elections held at the end of that month, Ernesto Zedillo Ponce de Leon, who had replaced Colosio as candidate for the presidency, won the elections; in Chiapas, where the lawyer and journalist Amado Avendaño, who was supported by civil society and the Zapatistas, presented himself as an independent candidate for the governorship of the State, a huge fraud took place and Eduardo Robledo Rincon was the winner, who took office as governor on December 8 in the presence of Ernesto Zedillo who had assumed the governorship on the 1st. At the same time, Amado Avendaño was sworn in as transitional governor in rebellion in the central square of Tuxtla Gutiérrez, a few meters away from the official act, a position he held until the end of the six-year term.

A few weeks after Zedillo’s inauguration, the “December mistake” occurred, in which, after decreeing the free fluctuation of the country’s currency, it fell to historic lows, dragging down the entire economy and generating one of the greatest financial crises in Mexico’s history.

Meanwhile, in the southeast, the EZLN, having completed its ceasefire commitment before the inauguration of Eduardo Robledo Rincón, began the military campaign “Peace with Justice and Dignity for the Indigenous Peoples” and, circumventing the military siege, appeared in 38 municipalities of the state and declared them Zapatista Autonomous Rebel Municipalities. The operation was carried out without any casualties and without any clash with the Army. The year ended with the Third Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle in which the EZLN calls for the construction of the National Liberation Movement.

IIf 1994 had been a year of heart attacks, the following year was not going to be any less so.

Original text by Lola Sepúlveda of CEDOZ published in El Salto on August 18th, 2024.

Translation by Schools for Chiapas.

Footnotes

- A small group of revolutionaries who operate in a country’s countryside.