In order to reflect on the states that are actually in existence, it is necessary to set aside ideologies and previous judgments to focus on what they are really doing or not doing, in their relationship with the native, black and mestizo peoples. Thinking about the State based on what the State has been doing in recent years is much more useful than going back to theories that are often based on other abstract theories that do not interact with reality.

A few days ago, Science magazine published a study on the access of the world’s population to drinking water: about 55 percent of the world’s population does not have access to safe drinking water, that is, 4.4 billion people, mostly living in the countries of the global South. “Fecal contamination affects almost half of the population in low- and middle-income areas,” reads the report commented by El País, which causes more than half a million deaths a year due to diarrhea (https://goo.su/8zgGpzl).

Of the total, 1.2 billion live in South Asia, almost 950 million in sub-Saharan Africa, some 850 million in East Asia, almost 500 million in Southeast Asia and more than 400 million in Latin America and the Caribbean. What are the governments doing to solve such a catastrophe? The answer is: little or nothing.

In reality, they limit themselves to promoting extractivism/accumulation by dispossession (mining, monocultures, large infrastructure projects, real estate speculation, etc.) that only aggravate climate chaos and water scarcity for those who cannot pay for it.

Although the aforementioned study does not include data from the global North or from some countries in the South, such as Chile and Uruguay, we know that there are enormous inequalities in access to water in these regions. In large Latin American cities such as Buenos Aires, Sao Paulo and Mexico City, there are entire neighborhoods with acute water deficits, which are not being addressed by the states.

In the country where I live, Uruguay, there has always been an abundance of drinking water of excellent quality. But in the last 30 years the deterioration has been evident, to the point that today the water we consume is not safe. None of the governments of these three decades, where progressives and conservatives have taken turns, took seriously the consequences of monocultures and livestock farming, which are responsible for the contamination of all the rivers.

States are merely facilitating accumulation by dispossession, in a variety of ways. Sociologist William I. Robinson argues in a recent article that “in this era of global capitalism, the system produces a historically unprecedented multiplication of surplus humanity,” people “too numerous to be useful to capital as a reserve army, unable to consume, restless and constantly on the move” (https://goo.su/9IzjUX). To contain them, because those at the top no longer aspire to integrate them, they resort to “a global police state whose contingent final aim is extermination.”

We are, then, confronted with states for extermination, whose greatest example is Gaza, which for Robinson “appears as a form of primitive accumulation through genocide.” It is the mirror in which the rest of humanity should look at ourselves.

The important thing is to understand that we are facing a structural reality, which no longer depends on who governs, i.e. who administers the State, which is what the art of governing is all about. Although they sell us “changes”, both the right and the left, when they are at the top, limit themselves to manage what exists. And what exists is dispossession, wars for dispossession.

This does not mean that there are no alternatives, but rather that we cannot continue to trust the states to provide the services that correspond to them. While in Mexico City several neighborhoods continue without water because high income areas and industries are privileged, in La Polvorilla (Comunidad Habitacional Acapatzingo) the organized community has achieved its water autonomy through the construction of three different sources. They do not depend on the irregular state service.

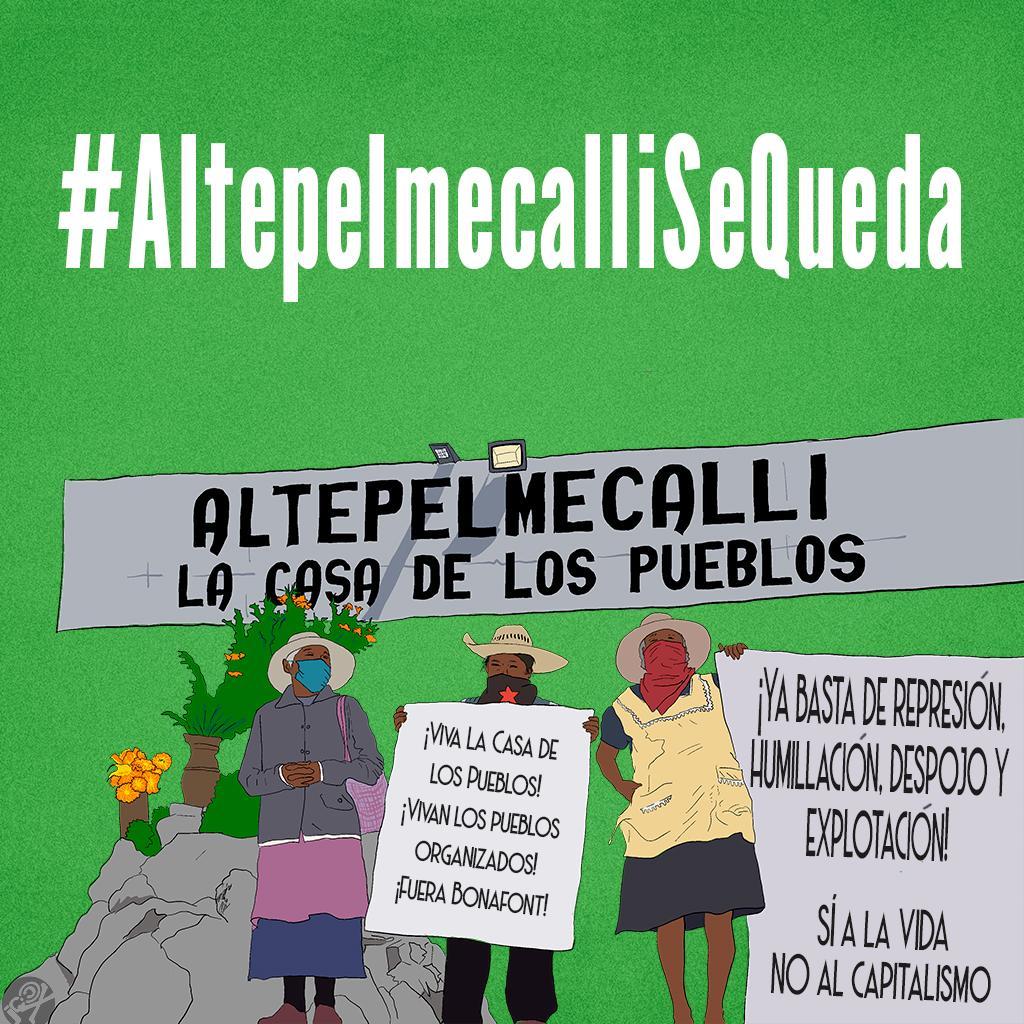

The great problem we face is that the vast majority of the population, at least in our continent, continues to trust the states and governments to solve their most urgent problems. When they fail to do so and take control of water, as Pueblos Unidos did in the region of the volcanoes of Puebla, the State’s response is repression so that the multinational Bonafont can retake the sources.

Even in the big cities, the most difficult scenario for the popular sectors, it is possible to advance in autonomies of all kinds if we are capable of organizing ourselves and looking far ahead, avoiding immediatism and avoiding the statist traps of the system. It is possible, but to do so it is necessary to sail against the current, to defy routine and capitalist disorder, particularly that which we replicate daily with total indifference.

Original article by Raúl Zibechi published in La Jornada on August 23rd, 2024.

Translation by Schools for Chiapas.