The most widespread and pernicious myth about the Rwandan Genocide may be that the US stood by and let it happen, but nothing could be further from the truth. The US in fact intervened aggressively—to make sure there would be no UN intervention—as Robin Philpot explains in Rwanda and the New Scramble for Africa: From Tragedy to Useful Imperial Fiction . This book is a classic history, as important this year, the 30th anniversary of the Rwandan Genocide, as it was upon its English publication in 2013.

At its opening, and in Chapter 7, “How is the Empire?,” Philpot quotes former UN Secretary General Boutros Boutros-Ghali, who said, “The genocide in Rwanda was one hundred percent the responsibility of the Americans!”

He quotes Boutros-Ghali’s 1999 book Unvanquished: A US-UN Saga in which the former Secretary-General writes, “The US effort to prevent the effective deployment of a UN force for Rwanda succeeded with the strong support of Britain.”

The 1994 genocide took place three years after the Soviet Union collapsed and broke up into 15 independent states. The Cold War was over and the US reigned supreme economically and militarily, with veto power on the UN Security Council. President Bill Clinton thus sent his UN Ambassador, Madeleine Albright, to systematically block any kind of UN military intervention to stop the bloodshed in Rwanda. No intervention would be tolerated, even if the US did not participate.

Why not? Because the US wanted to see its imperial proxy, the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) led by General Paul Kagame, seize power in Rwanda’s capital, Kigali. It wanted to displace France and the French language and establish itself as the dominant power in East and Central Africa. It wanted ready access to the immense mineral wealth of Rwanda’s neighbor, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which Rwanda and Uganda would invade two years later. It wanted to destroy the strong state established by the Rwandan social revolution of 1962, which overthrew the feudal Tutsi monarchy. The RPF, who carried US interests and the English language into Kigali, were largely Tutsi aristocrats who had taken refuge in Uganda after that revolution.

One hundred days that ended a four-year war

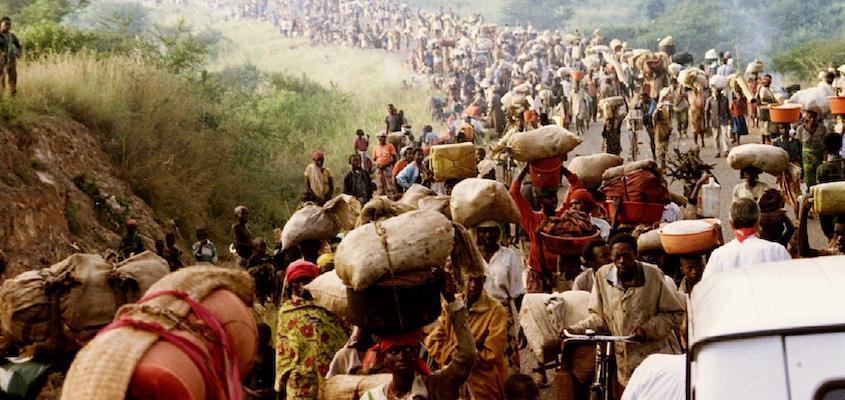

The popular understanding of the genocide is that it was 100 days of bloodletting in which the country’s Hutu majority executed a plan to exterminate the country’s Tutsi minority. Few, even in left circles, understand that it was the final hundred days of a four-year war that began when the army of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) invaded Rwanda from Uganda on October 1, 1990, displacing perhaps as many as a million Rwandans over the next four years. It is little understood that the US was determined to see its proxy, the RPF, win that war, or that the RPF also committed mass atrocities, including the assassinations of the Rwandan and Burundian presidents which triggered the panic, chaos, violence, and horror of the next 100 days. It is little understood that, immediately after the assassinations, the RPF broke the ceasefire in the four-year war, beginning a long-planned and conclusive military assault to seize power, which it accomplished by the first week of July 1994.

Philpot cites classified internal Clinton Administration documents which were made available in August 2001 consequent to a Freedom of Information Act request submitted by the independent National Security Archive. “These memoranda, telegrams, working papers, reports, and briefing documents,” he writes, “confirm the worst apprehensions about how a superpower develops and applies a foreign policy in which its own strategic interests take precedence over the lives and the peace of a country, its people, and whole regions of Africa.”

The Clinton Administration was well aware of the enormity of the tragedy unfolding in Rwanda after the RPF assassinated the Rwandan and Burundian presidents. Prudence Bushnell, US Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs at the time, warned Secretary of State Warren Christopher of “widespread violence,” and, Philpot writes, “a Pentagon memorandum to Under Secretary of Defense Frank Wisner, who was third in charge, warned that ‘unless both sides can be convinced to return to the peace process, a massive (hundreds of thousands of deaths) bloodbath will ensue. . . In addition, millions of refugees will flee into neighbouring Uganda, Tanzania, and Zaire.’”

What did the US push for in the face of these warnings, as the Rwandan armed forces were offering a cease-fire? It pushed for a drawdown of UN Peacekeepers, the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda, from 2500 to 270 troops as of April 21, 1994, three weeks after the assassinations that triggered the massacres. Earlier it had successfully pushed for keeping the peacekeepers to 2500, despite an earlier agreement to increase them to 4500.

Useful imperial fiction

The myth that the US simply stood by and indifferently let the genocide happen, or even that it wasn’t fully aware of what was happening, is, as Philpot writes, a “useful imperial fiction.” It’s since been enshrined in the mission statements of the genocide prevention complex, from the US National Holocaust Museum to the US Atrocities Prevention Board (APB), an interagency committee consisting of officials from the National Security Council, the Departments of State, Defense, Justice, and Treasury, USAID, and the intelligence community, which meets monthly, putatively and laughably to assess the long-term risks of atrocities around the world.

With epic hypocrisy, President Obama cited Rwanda in the August 2011 presidential directive creating the board:

Sixty six years since the Holocaust and 17 years after Rwanda, the United States still lacks a comprehensive policy framework and a corresponding interagency mechanism for preventing and responding to mass atrocities and genocide. This has left us ill prepared to engage early, proactively, and decisively to prevent threats from evolving into large scale civilian atrocities.

By that time Rwanda had already been profusely cited as an excuse for bombing Libya. After the gory, summary execution of Muammar Gaddhafi, UN Ambassador Susan Rice had landed in Libya and then flown on to Rwanda to say, “We got it right this time.”

The US/NATO bombing of Syria, which began in 2014, also followed many months of exhortations to “stop the next Rwanda.”

In Slouching Towards Sirte: NATO’s War on Libya and Africa , Max Forte wrote, “Everywhere is Rwanda for the humanitarian imperialist, which makes one want to know what really happened there in 1994.”

Robin Philpot’s Rwanda and the New Scramble for Africa: From Tragedy to Useful Imperial Fiction is one of the best places to start.

Ann Garrison

Black Agenda Report